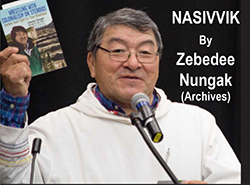

NASIVVIK By Zebedee Nungak,

Windseaker Columnist; Archives 2003

Nasivvik is an Inuktitut word that means vantage point. It can be a height of land, a hummock of ice, or any place of elevation that affords observers a clear view of their surroundings to make good observations.

On April 5, 1939, the Supreme Court of Canada issued a decision that stands out as one of the most memorable strokes of pen in Inuit history. The question that the court considered was: Does the term "Indians", as used in head 24 of section 91 of the British North America Act, 1867, include Eskimo inhabitants of the province of Quebec? The Supreme Court's answer was Yes.

"Eskimo inhabitants of the province of Quebec are "Indians" within the contemplation of head no. 24..." and so on and so forth... The decision's 21 pages are a showcase of the sophisticated ignorance that existed in Canada's establishment on identification of different Indigenous collectives.

The dense-mindedness in this decision can serve as a how-to guide on creating legal fiction with immense consequences. How this question landed in the chambers of the Supreme Court was a Keystone Kops comedy in governing. The Hudson's Bay Company had owned vast tracts of land, called Rupertsland, by royal charter since 1670. It had transferred its property to the newly-formed Dominion of Canada in 1870, but the Company was still the only entity, even in the 1930s, in the absence of government of any sort in the vast Ungava Peninsula which "possessed considerable powers of government and administration."

During times of scarcity and hunger in the 1930s, the HBC had extended welfare credit to Inuit in what was now Arctic Quebec, thereby serving a government function. With knowledge of which jurisdiction had been endowed with the latest territorial annex in 1912, the Company sent an invoice to the government of Quebec for what it had spent for these purposes.

Upon receipt of the invoice, the Quebec government refused to pay, citing a section of the British North America Act of 1867, Section 91 (24), which placed "Indians and Lands Reserved for Indians" under Federal jurisdiction. Quebec's point to the federal authority was, 'These are your Eskimos! You pay!' For its part, the federal position was, 'We gave you the territory back in 1912 lock, stock, and Eskimos! You pay!'

So, over the question, Whose Eskimos are these?, this case got launched before the highest court in 1936. Of course, the Inuit themselves were never told, informed, or asked about the whole affair. Colonial rule, in its arrogant self-confidence, would determine in which legal square to place these Esquimaux. The existence of the resulting court decision of 1939 would not become known by Inuit in Quebec for more than three decades. Their very place in the country's legal structure was the central questions in the case, but it turned out that there was never any reason to celebrate this decision.

Who could write a better script than this?

The government of Quebec triggers the case against the federal government after refusing to pay an invoice from the Hudson's Bay Company for welfare it extended to Inuit. Furthermore, Quebec formally pleads that a segment of its citizenry, occupying the top third of the province's land mass, is none of its business! Quebec goes to the Supreme Court, and wins, having these Eskimos declared federal responsibility! The court took three years to bludgeon a fictional answer to a ridiculously simple question: Are these Eskimos just another tribe of Indians?

The question was treated as one of the deep mysteries of the universe. The court took the task seriously enough to "consult the reliable sources of information as to the use of the term "Indian" in relation to the Eskimos in those Territories." For enlightenment on the matter, the justices went to Hudson's Bay Company records, colonial Governors' reports from the 1760s, several dictionaries, and a high and mighty-sounding Imperial Blue Book. No less than seven different variations of the word "Eskimo" were gleaned out of these sources, which contained passages such as, "They are called "savages", it is true... he speaks...of the Esquimaux as the 'wildest and most untameable of any' and mentions that they are 'emphatically styled by the other Nations, Savages'."

You can't get any more distinct than that! What in the end got defined was that: 1) Inuit living in Quebec were Indians for the purpose of legal definition, and 2) They were under federal jurisdictiion. It seemed that we were blessed by the decision with tax exemption and federal protection against future efforts of Quebec to separate from Canada.

For the Inuit, being called Indian is a useless piece of fiction, and this decision was a millstone, not a milestone. The Inuit subject to this decision are the highest taxed citizens in Canada. And, far from enjoying protection as federal subjects against the threat of separation from Canada, we have had to defend our place in Canada on our own every time that threat is trotted out.