Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

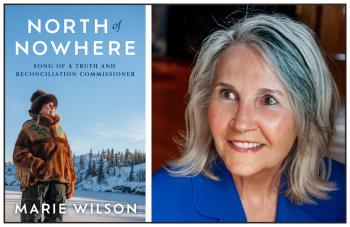

Marie Wilson’s memoir North of Nowhere: Song of a Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner is truly a song of love and hope for a nation and its people.

“What the book itself is trying to make plain is this is our story, everybody's story,” Wilson told Windspeaker.com. “And for Survivors, yes, this is your story here. And for Canada, this is our story…. all of us.”

Wilson was the only non-Indigenous commissioner on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) panel of three, which included former justice Murray Sinclair as chair and Chief Willie Littlechild. The commission delved into the legacy of Indian residential schools. The tenth anniversary is fast approaching on the commission’s 94 Calls to Action, recommendations for reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and Canada, released in June 2015, and the TRC’s six-volume final report on its findings, released in December 2015.

And as much as North of Nowhere is the story of Survivors and a story for Canadians, it is very much Wilson’s story of personal pain and personal triumph.

As Survivors laid bare the abuses suffered at residential schools with their testimony during the TRC’s five years (2009-2014) of activities—national gatherings hosted across the country and regional and smaller gatherings—Wilson reciprocates in North of Nowhere by sharing her own intimacies.

“The point of it was to make it clearer that I was telling my story and that this (serving on the commission was) hard work and that part of what unfolded was triggering for me too,” she said.

“I was living with things in the backdrop of my own life and then the backdrop of my own children and the backdrop of my own grandchildren and in the backdrop of my own mother-in-law, brother-in-law, sisters-in-law.”

Now knowing the heavy personal toll the Survivors’ stories would have on her, Wilson is uncertain if she would have declined the position of TRC commissioner.

“I can never unknow that, so I don't know the answer to that question. It was what it was. I went with a good heart and good intention and good purpose, good support, good skills and…I offered what I had to offer and then, basically, stood back from it and said, ‘Well, what will be, will be, and if I'm meant to be there, then I'll give it my best.’ And I did do that throughout,” she said.

None of the commissioners, she points out, served on the TRC “in a vacuum.” Sinclair was raised by his grandparents, residential school Survivors. Littlechild is himself a Survivor from Ermineskin Indian Residential School. Wilson is married to a residential school Survivor, who served as premier of the Northwest Territories (2000-2003).

For Wilson, a seasoned journalist in Canada’s north, it was difficult to write herself into the story. That’s not something journalists do, she says. But Wilson did it with both honesty and vulnerability. She recounts openly the struggles she and husband Stephen Kakfwi faced and were just coming out of when she took up the TRC position.

“I had fresh memories of our family implosion, marriage disintegration, two-year separation, and eventual reconciliation. The crisis was largely fuelled by my Survivor husband’s residential school experiences. His first sickening efforts to face the long-buried facts of what had happened to him eventually blew up our family. It was a long, painful crawl back to a shared life,” she writes.

She recognized that she would have to strike a “fine balance” in how she got support from the home front as the hearings unfolded and the words of Survivors painted the true horror of human depravity.

Along with family, friends and fellow commissioners, Wilson’s self-care was also provided by the health support team, a spiritual advisor, physical activity, and as the process went on, from Elders and Survivors themselves.

Wilson meticulously kept journals during the course of the TRC. It’s these notebooks she drew from in writing North of Nowhere. She admits that the trauma she experienced in revisiting that time for the book was unexpected.

“I hadn't foreseen it, and I hadn't thought it through enough,” she said. “You're certain your emotional fibre is stronger and indeed it is, but it doesn't mean that you don't still register it and feel it.”

Her journals were so detailed there were times she relived the incident. Wilson says she could picture the person speaking, picture what they were wearing, picture the room where the exchange had taken place.

“The things that I've inserted about my personal life (in the book) is because those were the things, for whatever reason, that came to mind while I was experiencing the commission…I didn’t call for those thoughts. That’s what showed up,” she said.

“Some of the others were things that came to mind while I was writing the book and then I am staring at my computer and trying to find the words to describe this and then things would come up then too…prompted in a way that saved me or…in a way that triggered me. So (the book) was a combination of those things.”

In writing North of Nowhere Wilson did not have the benefits and supports provided through the TRC process, but she did have the benefit of experience. She made sure to “get into my body and out of my head and out of my heart” by hiking, kayaking and cross-country skiing, and ensuring her writing retreats were in locations that allowed for self-care. She also had her family and extended family close by and continued to call on her spiritual advisor.

She also reached out to members of the health support team she had remained close to for care and to get their feedback on certain passages in her book.

“I wanted to vet the section with them and get their input on whether they felt that was responsible to be putting that out or was I going too far,” she said.

Wilson also kept in touch with Sinclair and Littlechild, both because she missed them and also to share the segments of the book that included them. She wanted to ensure they were comfortable with those portions. She also shared her book in its entirety with them before publishing.

Sinclair never had the opportunity to provide written support of Wilson’s work as both his and his wife’s health were failing. Sinclair passed away Nov. 4, 2024.

But Littlechild endorsed North of Nowhere, writing in part, “From shattered families comes the power of hope, to forgive, to respect.”

“The power of hope” is carefully curated in Wilson’s retelling of the Survivors’ stories.

Each chapter of North of Nowhere corresponds to the seven national events in the order they took place and each of those chapters highlights one of the seven grandfather teachings. Those teachings—love, wisdom, respect, honesty, humility, courage and truth—were represented by the seven flames of the TRC logo.

“There's always something hopeful and positive and I tried to do that in the chapters, and I tried to do it in each section, and I tried to do it in the book overall. I often say that to readers… ‘If you start a chapter stay with it to the end of the chapter. Don't bail in the middle of the chapter because it might leave you in a harder place… (before you) get the benefit of the lift that I think is there’,” she said.

That “lift” is also found in the words of Kakfwi’s song that comes in the beginning of North of Nowhere.

“I took a liberty with his permission on the last line because…he was down in the depths of his song,” recalled Wilson. “I said to him, ‘So what are you going to do? Are you going to stick around down there in the pits forever, or are you going to lift yourself out? And by the way, might you offer this gift, or is it just your story or for other people?’ …So, it's his outreach to other Survivors, to say, ‘I know this wasn't just me. It was so many of us. It was all of us’.”

The changed lines in Kakfwi’s song in the book take it from his personal struggles of being locked away, forced to pray and silently crying, to the plight of all residential school Survivors. At the end of his song, he goes from talking about the experiences as being “in the walls and the halls of my mind” to “Be free from the walls and the halls of your mind.”

Perhaps there is a symmetry that the verses of Kakfwi’s song, the first he ever wrote, are included in Wilson’s book, North of Nowhere: Song of a Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner. She says she toyed with the words “story” and “journey” before settling on the word “song” in the title. Song of the Northwind is the name she was given in a ceremony in Inuvik.

Released in June 2024, Wilson is pleasantly surprised that her book has become a Canadian bestseller. She admits she was concerned that she had taken too long to deliver it but knows she couldn’t have done it sooner or faster. North of Nowhere has grabbed the attention of schools, universities, book clubs, libraries, faith communities, and even the United Nations. Wilson has speaking engagements into October.

“I care so much about this story being known and understood and not forgotten and not denied,” she says.

And this Canadian story is something that’s resonating even more so today with United States President Donald Trump’s threats of tariffs and making Canada the 51st state.

“What's going on in North America right now, if we need a case study example of what happens when one group of people decides that it knows best what's good for another group of people and the dire consequences that can have, we don't have to look hard. And we need to remind ourselves of that because it's playing out on a much wider scale right now,” said Wilson.

It’s not about being judgemental about Canadian patriotism, she adds.

“Anytime we can bind ourselves around something that is for a more noble cause, including our own improvement as a human family, then that's the side that I can be supportive of,” said Wilson. “We can't change this past, but we can definitely see what principles we believe in, stand for and think about.”

North of Nowhere: Song of a Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner is published by Anansi Press and is available in bookstores and online, including https://www.amazon.ca/North-Nowhere-Truth-Reconciliation-Commissioner/dp/1487011482

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.