Image Caption

By Barb Nahwegahbow

Windspeaker Contributor

TORONTO

A research report released Sept. 20 says the population at Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong First Nations are suffering from mercury poisoning. This includes those below the age of 30.

Dr. Masanori Hanada headed up a team that travelled from Japan to do the research for the report. Japanese experts on Minamata disease, a neurological syndrome caused by severe mercury poisoning, have been working with the communities since the 1970s. Their report contains findings from research conducted in 2014 when they visited the communities with a medical team.

Between 1962 and 1970, with the province of Ontario’s permission, Dryden Chemicals Inc. dumped 20,000 pounds of mercury into the Wabigoon River system upstream from Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong First Nations.

“We found that more than 90 per cent of the population in these communities have sensory disturbance,” said Dr. Masanori Hanada. This is one of the first symptoms of mercury poisoning, he explained.

Dr. Hanada is a founder of the Open Research Centre for Minamata Research and is the Dean of Social Welfare and Policy, Minamata Studies at Kumamoto Gakuen University.

“The study confirms what we’ve known all along, that we’ve been poisoned, that we have symptoms of mercury poisoning” said Simon Fobister Sr., the Chief of Grassy Narrows.

“Even to this day,” said Chief Fobister, “the government of Canada and Ontario will not admit there is Minamata disease in our communities.” They say, “that the symptoms are likened to mercury poisoning, but they’re not saying outright that this is Minamata disease,” said the chief.

Dr. Hanada said his team has the knowledge and experience to recognize Minamata disease, and “we see they have Minamata disease. Canada needs to accept this. That’s the starting point.”

Chief Fobister said the years of mercury pollution and other environmental degradation in their community has created massive social upheaval with marital breakdowns, unemployment and suicides.

“Since 1970, our livelihoods were taken away,” he said. “I could not tell you how many millions upon millions of dollars of damage has been done to our community.”

Not only did they have an economy based on fishing, but “we have consumed fish for sustenance,” he said. Wild rice fields have been destroyed because hydro development has caused erosion leading to high water levels.

Chief Fobister said nearby municipalities dumping raw sewage in the river and there is threats from clear cutting. The clear cutting will compound the mercury pollution and contamination in the river system.

“Until we resolve the issue, no one’s going to make a living out of harvesting wood on our traditional land,” said the chief. “Not even us.”

“Our right to live was taken away. This is our Aboriginal and treaty right, so are we happy about it?“I don’t think so.

“If somebody contaminated your water supply, I don’t think you’d appreciate that very much. If somebody contaminated your food source, I don’t think you’d appreciate that very much.”

There are several things the government has to do, “and we need action now,” said Fobister. The river needs to be cleaned up or else it will continue to affect even younger generations.

In Japan, they were able to return to commercial fishing 25 years after the clean-up of their mercury-polluted water system. Scientists say our river system can be cleaned up, Fobister said, but there is no clear and solid commitment from the Ontario government that a clean-up will take place.

The majority of people who were examined by the Japanese team and found to be suffering from mercury poisoning are not receiving awards from the Mercury Disability Board, “and that’s a disgrace,” said the chief.

Canada and Ontario have a duty to revamp the legislation so that it works for us, he said. There has to be proper testing by Canada and recognition by the government that mercury poisoning does exist in Grassy Narrows and Wabaseemoong.

The chief said he is engaged in discussions with Premier Kathleen Wynne about building and restoring their economy. “No one’s giving us anything,” he said. “We have to fight for everything and that’s a shame.”

Peter Tabuns, the environment critic for the Ontario NDP, said he has been raising questions in the legislature about Grassy Narows.

“It is an incredibly shocking fact that nothing’s been done,” said Tabuns. “It appears that the government strategy has been neglect and they didn’t do that at Walkerton when people were poisoned. If this had happened on the Credit River here in the (Greater Toronto Area), it would be cleaned up. I can see no humane thoughtful reason why they’re neglecting this.”

Other symptoms of mercury poisoning include lack of coordination and tunnel vision.

“Unfortunately, there’s no going back,” said Dr. Hanada. “This disease affects the brain, it deteriorates. The health of the person with Minamata disease either stays the same or it gets worse as they age. There’s no cure.”

Chief Fobister is concerned about the young people in his community who were found to have symptoms.

“The young people are really upset,” he said. “They know they’re sick. They know they have symptoms and they’re very scared. We need to find a solution now.”

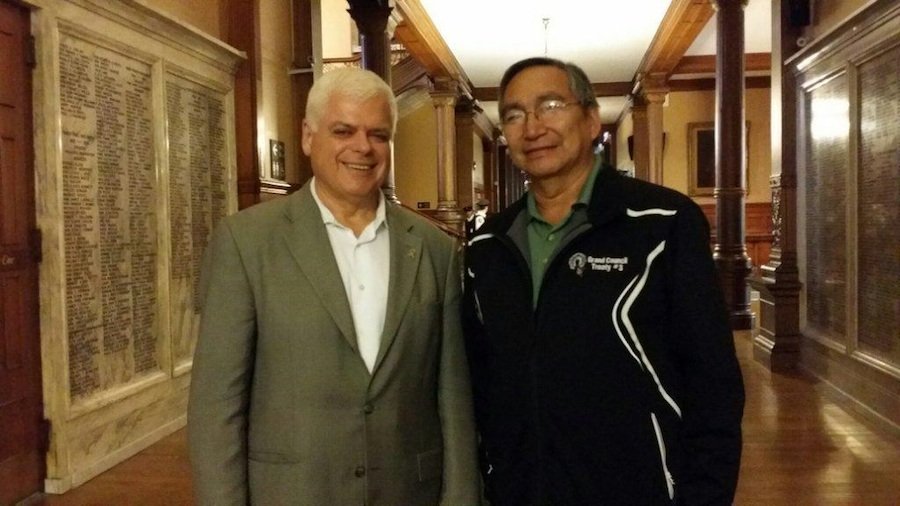

Chief Simon Fobister of Grassy Narrows First Nation with Peter Tabuns, Ontario NDP Environment Critic, at Queen's Park on Sept. 20.

The Japanese research team at a Toronto press conference to release the research report on Grassy Narrows First Nation on Sept. 20. From left to right: Kana Nemoto, Dr.Naoki Morishita, and Dr. Masanori Hanada.

Photos: Barb Nahwegahbow