Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

The head of an Indigenous organization that advocates for sustainable and responsible resource development is pushing for “meaningful talks” to happen with Indigenous communities on how to move forward on a 42 per cent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction target set by the federal government for 2030.

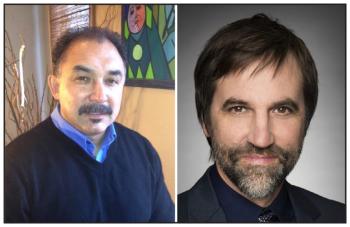

Robert Merasty, executive director of the Indigenous Resource Network, calls that target a “political statement.”

“That’s what I disagree with: Political people making their own statements without consulting with … rights holders... In our Indigenous communities, we are rights holders. We have, absolutely, certain rights that are identified within the Constitution of Canada. You need to have meaningful talks,” said Merasty.

“It’s really (been) an issue of government dictating what must be done instead of sitting and discussing and asking what should be done. That’s the fundamental approach here.”

Federal Environment and Climate Change Minister Stephen Guilbeault says consultations have happened and he continues to speak with Indigenous communities and leaders.

In June 2021 the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act was passed, committing Canada to achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

The Emissions Reduction Plan, published this past March, states 30,000 Canadians had input, including Indigenous peoples. It sets out a 42 per cent emissions cap on the oil and gas sector by 2030 as one of the tools to hit the zero emissions mark by 2050.

“We did consult in preparing this plan,” said Guilbeault. “It’s not something that we did on our own in Ottawa. There was a lot of consultation. I’m hearing from some Indigenous representatives that there are too much consultations that we’re doing right now on environmental issues or climate change.”

What that plan doesn’t take into account, says Merasty, is the impact such measures will have on the quality of life of Indigenous communities that have finally been able to raise the capital needed in order to partner in oil and gas development.

“Nobody supports the protection, the stewardship of our Mother Earth more than our Indigenous communities…that’s paramount. But we also have to address the dilemma of how we address the poverty,” said Merasty.

Energy projects, such as Coastal GasLink, which will deliver natural gas from the Dawson Creek area to a facility near Kitimat and has considerable Indigenous buy-in (although there are Indigenous communities that oppose the project as well), have the ability to provide Indigenous communities with tens of billions of dollars that can be used to improve their quality of life, says Merasty, and move them away from dependence on federal funding.

“So let’s sit down and talk about what’s digestible in terms of addressing our climate change. Let’s sit down and talk about how do we do it together. Because in the midst of an energy crisis that Canada is having, we can’t simply shut off our energy productions and (be) purchasing our energy from other countries. That does not make economic sense,” Merasty said.

Merasty doesn’t stand alone with his concerns about how climate change measures could impact Indigenous communities economically.

The First Nations Financial Management Board (FMB) has raised concerns over the mandatory guidelines set by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) for how companies on the stock market will be required to disclose their GHG emissions.

“GHG reporting will likely have a negative effect directly and indirectly on the Indigenous economy, but, at the same time, it will not include reporting on the value of Indigenous stewardship of traditional territories or “natural capital.” The value of this stewardship is far in excess of GHG emission reporting penalties and additional costs that Indigenous businesses, individuals and governments may face,” wrote the FMB in a February letter to the CSA.

The FMB works with First Nations to help them establish strong financial practises and secure loans.

FMB also raised concerns that GHG reporting may have an impact on Indigenous communities and businesses that operate in remote parts of Canada if they were required to report GHG. FMB notes that these communities and businesses rely heavily on GHG-intensive electricity and transportation.

Guilbeault says Indigenous communities are not required to report on GHG emissions.

“As for the use of fossil fuels by Indigenous communities in remote areas, we’re very mindful of the fact that right now there are some partial solutions to diesel being used in that context,” said Guilbeault.

He points out that already some remote Indigenous communities have financed green projects themselves and rely more on wind or solar energy than diesel. Other communities, however, have set different priorities.

“We want to work with communities. The idea here is not to impose an Ottawa-knows-best solution. We have to work in partnership with those communities and at the pace that they need,” said Guilbeault.

In April, the federal government announced $300 million in funding for clean energy projects for Indigenous communities.

As a means to tackle climate change as well, Canada has set a goal of protecting 25 per cent of land and inland waters by 2025. The creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) is an integral part of that strategy and the federal government has set aside $40 million for this work.

To that end, Guilbeault announced last week that $3 million had been awarded to Miawpukek First Nation in Newfoundland to support their area-based conservation work and establishment of a new IPCA. The money will also fund four Indigenous guardians to document conservation values and continue the traditional ways of life on the land.

IPCAs and other conservation efforts aren’t considered carbon offsets for GHG emissions.

“There are projects around the world that are exploring the possibility of doing that,” said Guilbeault. “We have launched some offset protocols in Canada, mainly for capturing methane gas coming out of landfills. Forestry credits are something we are exploring. Would we do conservation? That's a good question and frankly one we would need to explore with communities.”

He added that there is both support and opposition to that concept, which is a “very emerging tool” occurring on the international front.

“I’m not sure where we would land on that. I think we would want to be careful with something like this. Then again, if creating credits is a way of raising more funds to be able to protect more areas, maybe this is an interesting avenue,” he said.

However, Guilbeault adds, nature-based solutions should not be confused with creating carbon credits. The purpose of a nature-based solution is to help adapt to climate change. Guilbeault points to a park created recently in Montreal that will be used to mitigate spring flooding.

“To me, there’s a very big difference between these two things,” he said.

In a few months Canada will be hosting the United Nation’s convention on biological diversity. The Conference of Parties 15 (COP15) will be held in Montreal from Dec. 7 to Dec. 19. It will focus on protecting nature and halting biodiversity loss around the world.

Guilbeault says Canada has proposed to the UN and China, who is presiding over the meeting, that Indigenous conservation and Indigenous knowledge be “front and centre.”

Merasty acknowledges that “Canada is absolutely on the international front” when it comes to leading the action on climate change, but that doesn’t mean fuller discussions don’t have to happen at home.

“Our Indigenous people have had a good relationship with this current government for the most part… Why can't we continue down…this path where we sit and we speak the truth…and the truth is, what is it that we can do together… in a responsible way?” said Merasty.

“The Canadian government cannot take away our right as Indigenous people to decide for ourselves what is ethically, what is environmentally, and what is economically responsible. They can't take that decision away from us,” he said.

Guilbeault says the federal government has no intention of doing that.

“What I’m hearing loud and clear from Indigenous communities all across the country…they’re all telling me we need to do more to fight climate change and that’s what we’re doing,” said Guilbeault.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.