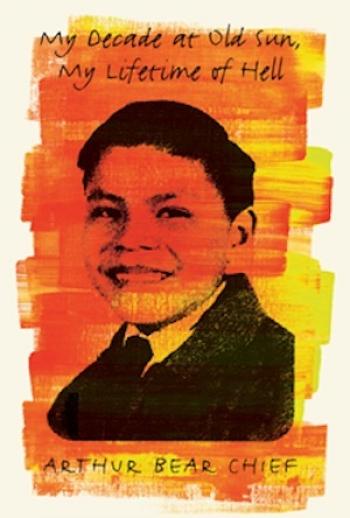

Image Caption

By Shari Narine

Windspeaker Contributor

SIKSIKA NATION, Alta.

Arthur Bear Chief said his is a story that needs to be told. Not only for himself, but for the other children who were abused at Old Sun residential school and can no longer speak out.

“It’s important for me to make public what I personally went through and also to speak for people that are gone that went to residential school with me and that went through probably the same thing that I did. There’s no voices for these people. I wanted the public to know,” said Bear Chief.

My Decade at Old Sun, My Lifetime of Hell will be published in December.

The book is the first accounting Bear Chief has had of the sexual abuse he suffered. He made a pact with Nelson Wolf Leg, who also attended the school near Gleichen in southern Alberta, that neither of them would talk about the sexual abuse they suffered at the hands of their supervisor Bill Starr, until one of them had died.

“My friend Nelson is long gone. When did he die? I don’t know,” said Bear Chief.

Bear Chief was seven years old in 1949 when he entered Old Sun residential school. He did not speak English. His physical abuse started his very first night when he couldn’t stop crying. Over the next 10 years, along with being abused and having his culture ripped away, he would be witness to the abuse suffered by other children.

Bear Chief hopes that by telling his story the public will understand that the financial settlement that came to residential school survivors through the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement will never be enough.

“We were told to take this, ‘now shut up and move on’. You’re supposed to heal,” he said.

But to heal, said Bear Chief, he needed to talk and that is how My Decade at Old Sun, My Lifetime of Hell came about.

He tried other means – like alcohol – to deal with “the demons that were inside of me.”

“By telling that, it’s given me some sense of peace. It will never go away. I will never get rid of this … and I’m trying to get over that final hump. It’s not necessarily smooth sailing for the rest of my life, but perhaps to defeat my demons,” he said.

For Frits Pannekoek, president of Athabasca University, it was important to publish Bear Chief’s story.

“It’s a very, very powerful story,” he said. “Arthur is very articulate. His writing is extremely powerful....His story is one that has a lot of strength.”

Pannekoek said one factor that swayed Bear Chief to publish his work with Athabasca University Press was that, as an access press, the book goes online and is available free of charge.

“He wants to be sure that everyone has the chance to benefit from his experience,” said Pannekoek.

The book will also be printed and sold.

Chief Bear’s residential school story includes the legal documents of discovery, work undertaken by the Merchant Law Group.

“You have access to all parts of his story. Arthur has nothing to hide,” said Pannekoek. “His story is very straightforward. It’s very honest, there’s no artifice or anything. Arthur is what he says.”

Pannekoek wrote the afterword to Chief Bear’s book. Entitled “The burden of reconciliation,” Pannekoek said it is important for non-Aboriginal people to understand the pressure that has been placed on Indian residential school survivors to reconcile.

A professor of western Canadian history, Pannekoek is well aware of the residential school experience.

“The abuse was systematic at worse, but most important of all, in virtually every one of the schools, there was an attempt to eradicate the culture. And that’s the single most, I think, serious of the crimes,” he said.