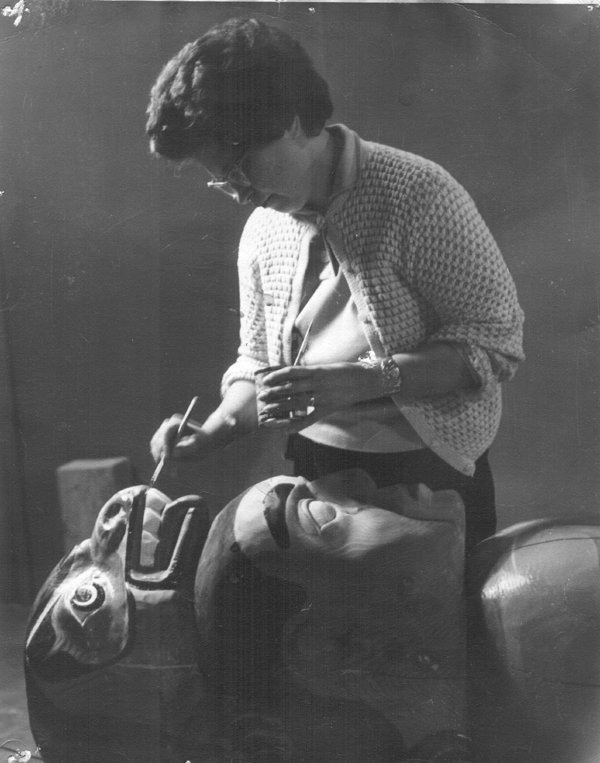

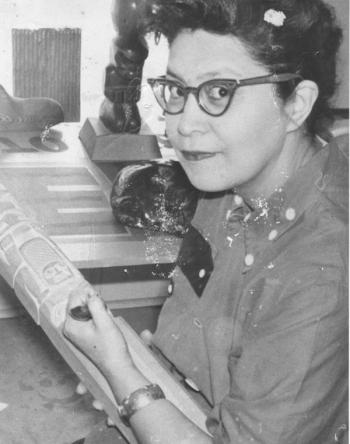

Image Caption

In the 1950s, if your family had a West Coast totem pole souvenir, chances are it was made by Kakaso’las, Ellen May Neel.

The Kwakwaka’wakw artist was born in a plank house in Alert Bay just off northern Vancouver Island’s inside passage. Her Kwakwask’wakw name, which she seldom used but with which she sometimes signed her totem poles, means “people who came from far away to seek her advice.” In Alert Bay, she was simply known as Ellenah.

“My grandmother was bed-ridden, so my mom always wandered down to the beach where her grandfather Charlie James had his carving shed,” explained Ellen’s daughter Cora Beddows.

Amidst the hammering and shouts of children playing, he taught her his craft. Lending a hand, too, was Ellen’s famous uncle, Mungo Martin.

When Ellen turned 10, her grandfather, appreciating her natural talent, increased the intensity of his instruction. He made her repeat drawings to his exact specifications amidst her stressful tears, but by the time she was 12 she could carve totem poles well enough to sell them to Alert Bay tourists.

By the time she was 18, Ellen had quit school.

“She married my father Edward Neel in 1938 and they moved to Vancouver in 1943,” said Beddows. “Dad hurt himself and couldn’t work, so my mother found herself having to feed and clothe six of us children. On Powell Street – it’s part of skid row now – in the 40s and 50s when women weren’t allowed to carve totem poles, there was mom carving and painting them.” Her little workshop slowly became a storefront business.

By 1946, Ellen had recruited her family to help her make small tourist totem poles. According to Beddows: “I can’t remember a time when the house wasn’t covered with wood or a day when mom didn’t work. One time she got an order for 2,000 poles from the Hudson’s Bay Company. My dad cut out the blanks with a band saw and my mom carved them. Us kids would paint them. I was assigned one colour to paint, like the brown on a bear.”

The small souvenirs were Ellen’s bread and butter, but she gave her heart and soul to the carving of commissioned full-sized poles for setting outside houses and in public places. Those assignments dribbled in, and she was more commonly asked to make “midway” poles about two to five feet high.

The pole itself was carved from a single piece of yellow cedar, but the top eagle or thunderbird’s wings were attached with “paddles” nailed to the back. The paddle “handles” were fitted into holes in the central column.

Ellen’s talent and prolific output of poles helped to revive the art form. Vancouver City councillors presented totem poles to visiting dignitaries, including Queen Elizabeth II, actor and singer Bing Crosby, and 50s actress Katharine Hepburn. Vancouver became known as Totemland, and Ellen’s work was collected internationally.

Vancouver Mayor Charley Thompson arranged for Ellen to provide the model for the totem pole used as the insignia for the Totemland Society, to promote tourism. Vancouver public relations officer Harry Duker also arranged for the Neel family to carve in a tent in Stanley Park, eventually helping them establish a permanent workshop and store at Ferguson Point, near Mohawk writer Pauline Johnson’s burial site.

Ellen sold her first polished totem to University of British Columbia President Norman Mackenzie. The Vancouver Province newspaper described the artist as “probably the only woman totem pole carver in the world.”

Soon after, she gave a 16-foot thunderbird totem as a gift to the UBC Alma Mater Society and gained more public esteem.

But by 1960, when she was only 44, Ellen began losing weight and her sight, and became so sick she couldn’t work at times. In 1961 her oldest son Dave was killed in a car accident and she failed to overcome the loss, sinking into a deep depression.

At the behest of her friends, Ellen applied for a Canada Council grant in 1963 to support her artistic development. Though she was a leading – and Canada’s first female – totem pole carver, she was flatly turned down. Friends say when the letter refusing help arrived, Ellen read it and sat for a long time staring into space.

With both parents sick, one of Ellen’s sons began selling family heirlooms to bring in cash. Ellen’s tools, her favorite drawings and carvings done by her grandfather Charlie James, and the family’s sacred copper were sold behind her back. When she found out, she and her sibling were furious. Her depression hit a new low.

Ellen entered the hospital in January 1966 and died on Feb. 3, worn out by the cares of her life.

“She did carry a huge load in life,” explained Beddows. “Our relatives in Alert Bay sent my cousins to live with us in Vancouver so they could get better schooling. There were two to three of us in a bed and the meals mom made were huge. Everybody cared for each other. The thing I admire most about my mom was the way she used her art to support us. She was firm, strict and loving all at the same time, but the strain of her work soon started showing.”

Though Beddows didn’t carry on the carving tradition, she’s done all she can to serve others as Ellen did. She served as president of the Friendship Centre in Courtney, B.C. she and fostered children for 28 years.

“My nephew David Neel carves in wood, gold and silver and his work is well known,” commented Beddows. A generation of artists like Freda Diesling and Doreen Jensen were also inspired by Ellen’s work.

“Mom was so generous in sharing her skills. She trained Phil Nyutten, and he can carve a mean totem pole,” concluded Beddows. Phil Nyutten is a Métis inventor, entrepreneur and deep-ocean explorer who authored The Totem Carvers, published in 1982, which features the work and lives of Charlie James, Ellen Neel and Mungo Martin. The book is a standard reference text in Northwest nature ethnography studies.