Image Caption

Windspeaker.com Books Feature Writer

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

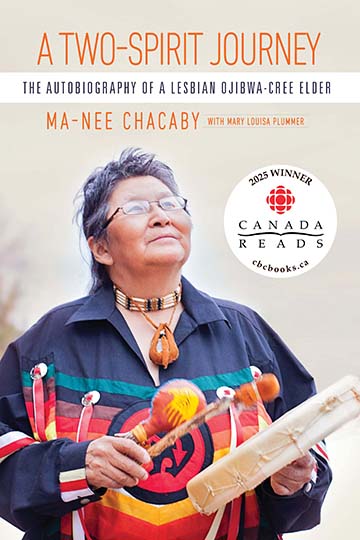

CBC’s competition Canada Reads recently celebrated a memoir published almost a decade ago.

“I am grateful that they picked the book,” said Ma-Nee Chacaby, Ojibwe-Cree author of A Two-Spirit Journey. “I didn't ever think it was ever going to go anywhere. I just wanted other First Nations to start writing their stories. That was my main thing. Maybe if I write, they’ll follow.”

A Two-Spirit Journey was published in 2016 by the University of Manitoba Press. Chacaby, who is visually impaired, told her story to non-Indigenous close friend and professional writer Mary Louisa Plummer over Skype during the course of several months in 2013. Plummer typed it and then read the first draft to Chacaby, who rounded it out with additional material.

A Two-Spirit Journey is an unflinching hard-hitting honest story of Chacaby’s youth in a small remote northern town in Ontario, suffering through poverty, becoming an alcoholic, being sexually and physically abused. But it’s also a story of hope and resilience as Chacaby works through her burdens to raise her children, counsel youth and women, and accept herself as two-spirited.

“It was important for me to talk about my two-spirit life. There's a male person inside of me and a female person inside of me, and I feel there's two of me, and I am privileged to have that kind of life, to be able to have the two-spirit in me,” Chacaby told Windspeaker.com

“The younger generations right now always think about it as a sexual being. It's not about that. It's about being alive. It's about respecting your body as a male side and a female side, and it's about the love that you have inside of your own body, mind and soul. That's how I think of my two-spirit life.”

A Two-Spirit Journey was the only Indigenous-authored book in the competition, beating out four others in the 2025 Canada Reads that had as its goal “one book to change the narrative.”

From March 17 to March 20, podcaster and wellness advocate Shalya Stonechild, a Red River Métis and Nēhiyaw iskwēw from Muscowpetung First Nation, defended A Two-Spirit Journey facing off against other celebrities who championed other books: Watch Out for Her by author Samantha M. Bailey, Etta and Otto and Russell and James by Emma Hooper, Jennie’s Boy by Wayne Johnston, and Dandelion by Jamie Chai Yun Liew.

Chacaby had never heard of the annual Canada Reads before her book took the stage. But for those four days she sat with three or four friends in her home in Thunder Bay, Ont. watching the debates on her laptop. At the end it came down to her book and Dandelion.

“When Canada Reads was happening during that week, I was watching it and sometimes I was excited. I would jump up and down. I was cheering for everybody that wrote a book. Then when it was my turn, I would also jump up and run the other way and, ‘Oh my God, did they call my name?’ I was kind of shy and scared,” said Chacaby, laughing.

She admits she finds it easier to cheer for others than for herself. For herself, “I get excited inside. But I don’t show a lot of emotions outside. I was very, very happy the book won.”

In defending and talking about A Two-Spirit Journey, Stonechild said in the final debate that the book was “a powerful act of resilience, of truth telling and of healing… It’s a Canadian story that challenges, educates, and transforms its readers.”

During that debate, other judges commented that Chacaby’s work was “such an important document” more than it was simply a story

“Us writers as Indigenous people, we are inherently educational and political just through being alive here…It made me question…would I be seen as an academic text if I wrote my story?” asked Stonechild.

“I want to think of it as a story,” said Chacaby. It was the story she needed to write to refute her friends who called her lucky for never having attended residential school. “I looked at them and I felt really like, ‘How do you know what the hell I went through?’ I didn't say that to them. I just thought about it that way.”

As for the comments made by the judges, Chacaby says she soaked it in.

“There was not a time where I tried to correct somebody or just say, ‘Oh, I didn't say it that way.’ I just listened to them. I just took it in the way it's supposed to be. I don't make judgments…I just take it in stride, I guess,” she said.

Chacaby, who is now 74 and sober for 50 years, continues to persuade other Indigenous people to write their stories.

“One lady talked to me yesterday. So maybe it’s going to happen,” said Chacaby.

Said Stonechild of A Two-Spirit Journey, “Canada needs this book because it amplifies a voice that usually would not be heard, and it shines a light on important experiences that would not be seen.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.