Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Technology and tradition may sound like an unusual mix, but it’s not when it comes to northern life.

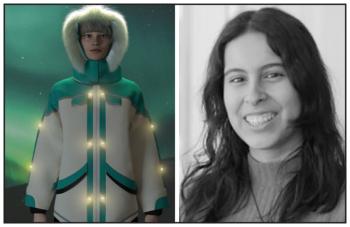

This past spring, Sofia Parra was among a number of industrial design students from Carleton University in Ottawa to make the trip to the Na-Cho Nyak Dun First Nation community of Mayo, Yukon.

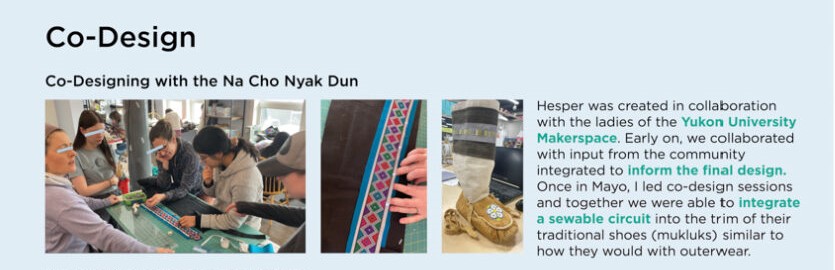

She met with a group of First Nations women at the Yukon University Makerspace program who were already helping her with the design of Hesper, a coat for the dark days and nights of winter.

Parra started working three years ago on the concept of Hesper, named for the Hesperides constellation containing the morning and evening stars.

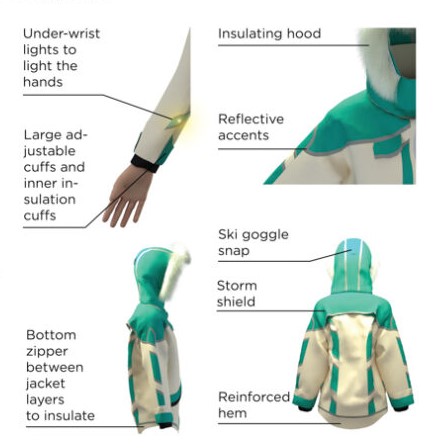

The coat lights up, activated by the heat of a human body. It is equipped with a lightweight circuit that allows modules embedded in the material to be powered by thermoelectricity, or the conversion of temperature differences to electric voltage. The heat is absorbed into one side of the light thermoelectric modules while the other side is exposed to the cold winter air.

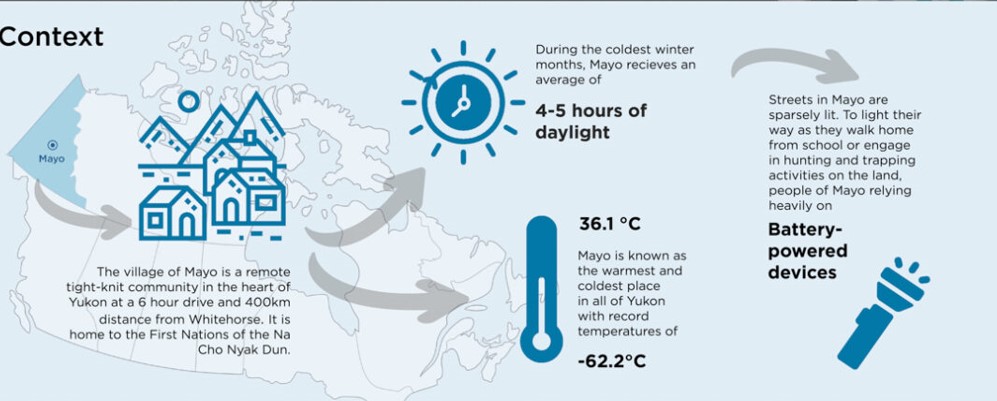

Unlike coats with reflective material, Hesper allows the wearer to “create the light yourself because there isn't much light to reflect off of in the first place there,” said Parra of Mayo.

The technology doesn’t make the coat any heavier, she adds, because the lights are connected to the modules by a flexible and lightweight stainless steel conductive thread sewn into the inner jacket.

The inner jacket can be removed for ease of maintenance. A rotating dial in the collar controls the brightness of the light-emitting diode (LED) of the coat.

Parra, who now has a bachelor’s degree in industrial design, is in the process of getting a patent for the jacket design. She expects the patent would focus on innovation and the way that the elements are being put together, as the variety of technologies already exist.

Even before the trip to Mayo, and the in-person contact, Parra had been collaborating with the women on design direction through hologram-type technology from Ottawa, which projected an image of full-scale prototypes of the coat to the northern community.

“So that's how I collaborated in the beginning. Once we got there, we were able to conduct co-design sessions and activities to be able to gather information on the technical details for our project and, also, just get their thoughts on everything,” said Parra.

That interaction and collaboration resulted in “really good elements” for the coat, said Lisa Preto, the community outreach manager with Yukonstruct, a non-profit society which partners with Yukon University on the Makerspace program.

“I can't imagine that (Parra’s) jacket would look like this if she didn't come up to the north and didn't talk to these ladies,” said Preto, who had also been involved with the Carleton students through Zoom. She made the trip to Mayo to meet and work with them.

“Just the innovation that can come from (living in the north). It’s just so different and often misunderstood in places like Ottawa. I think connecting those students with these women in a really respectful way, and for the students to learn from the folks of Mayo, is really an amazing opportunity for them to talk to people with traditional knowledge,” said Preto.

Parra said she used elements of the Na-Cho Nyak Dun cultural identity for Hesper, but “not in a copy-paste kind of way, but in a way that alluded to those elements being present.” Elements incorporated included the layers of traditional coats, colours and trim.

Preto is impressed by the design.

“The jacket looks beautiful, and the fur is an old technology that works really well,” she said.

“Sewing with fur…I’d like to think of it as the very first art form that there ever was, because it was so useful and people have been sewing garments made out of fur since they first lived in the Arctic, in the north. Hunting, gathering and sewing fur were what sustained people for centuries,” she said.

Preto likes the cuffs that close and the really high neck shield. The traditional design of the scoop in the back and the front allows for easy walking, climbing and sitting on a snowmobile. The shoulder design allows for easy movement of arms to “lift firewood” or do other work. The vent flap in the back takes into account the need to be warm when riding on a snowmobile and the need to cool off when working.

“A lot of these traditional elements just still work today because they're just so clever and people living in the north would be the ones that know what works and what doesn't work,” she said.

Two suggestions Preto offered for the design are a zipper flap to prevent the wind from blowing through the zipper and wrapping the fur from the hood all around the face. When fanned out around your face, she says, the fur serves as a wind disruptor, creating a vacuum and preventing the wind from blasting into the face.

Parra envisions the jacket being used by hunters and trappers in wintertime.

However, something new like this may take a bit of time to catch on, says Preto, a hunter and a trapper herself.

“Generally being the bush, we really like old, low-tech things just because things can break down and it gets a lot riskier,” she said. “I am leery of new technology for serious country stuff.”

Preto said other students had other ideas, such as developing a trailer to be used both in the summer behind a quad and in winter behind a snowmobile. There was also talk about developing a silicone sole for mukluks.

“It was looking at all these opportunities of the things that we make-do with as those are the opportunities for technology and new ideas,” she said. “Things like that could be just so great without taking away from the traditional knowledge, but just incorporating it in a really respectful and acknowledged way.”

Preto is pleased with the collaboration that has produced such a fine garment in such a respectful way. But she says that respect needs to continue and Parra has to be clear that the northern technology jacket was designed “in partnership with (and) knowledge from” the Mayo women.

Otherwise, it is cultural appropriation.

“First Nations people have always adapted as new technologies were brought to the north. So not trying to take their traditional practices away, but incorporating technology into what traditionally is amazing engineering already is a good way to move forward as long as there's a lot of acknowledgement and…there’s no cultural appropriation,” said Preto.

Parra sees Hesper as an economic opportunity for the women in the First Nations garment program. They can manufacture the jackets and sell them both locally and internationally to generate a self-reliant source of income.

“With Hesper, the Na-Cho Nyak Dun can share their culture and values with the world in a garment that is also a tool, empowering them to continue living with the land as they have for generations,” said Parra.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.