Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Ritchie Hemphill, ’Nakwaxda’xw, is a West Coast filmmaker who has co-founded a stop motion animation film studio called Bronfree Films.

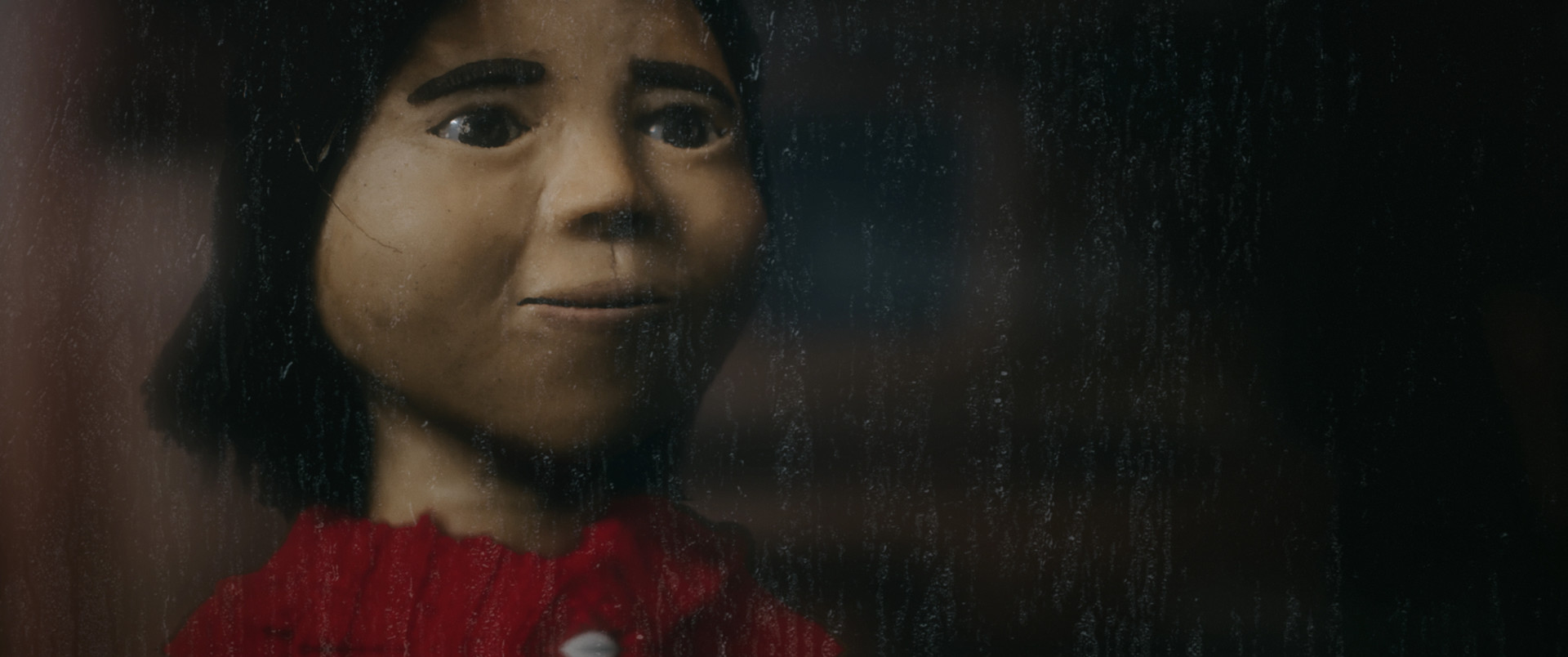

His latest project, Tiny, is a documentary short, created with his mother’s voice and stories. Hemphill describes it as a “slow-tone poem,” a tribute to “life integrated with nature.”

The inspiration for Tiny is Hemphill’s mother, Colleen.

“She is my main role model, and hero in my lifetime for sure.”

The main goal of making the film was to share her stories “to give that physical feeling of the different way of life,” said Hemphill.

Hemphill and film partner Ryan Hache have often made “quite niche, abstract films.” Tiny, however, was created in “an effort to reach as wide an audience as possible, to be relevant for everyone.”

The film portrays Colleen now, as an Elder, reflecting on her past, re-enacting her stories as a young girl growing up on a float-house on the wild and unpredictable West Coast. Although it is documenting real-life stories, Tiny has a surreal, dreamlike quality that brings viewers into the story’s time and place.

While making Tiny, he first visited his original homelands across the water from where he grew up on Tsulquate reserve at Port Hardy on the northern tip of Vancouver Island. His people had been forcibly relocated to Port Hardy in 1964, and their villages burned down by government agents. While visiting their lands, his mother Colleen shared how “the earth itself provided so much for the people.” With that abundance, she shared “a sense that there was a lot more time for people to explore their souls, or art making.”

“The Earth could provide. It's not speed and productivity that's going to feed everyone. I think feeding our souls is more important,” said Hemphill.

He reflects on the impression that the landscape of his childhood left on him, along with the community connections that raised him. Tsulquate has about 600 people, “surrounded by forest and the ocean.” He remembers living closer to the land as playful and carefree.

One of the challenges to making Tiny was the pandemic and being a seven-hour drive from his mom, and COVID precautions. He recorded six hours of her storytelling in one visit.

There was a deep responsibility to craft the story with care, working with his mother’s voice, sharing vulnerable moments, and wanting to respect the stories. Because he was working on scenes that he hadn’t experienced himself. It was important to check in with Colleen until it was right.

She’s been a role model in her well-organized, thorough knowledge keeping. She has worked extensively with school districts and language keeping, wrote her first script for How a People Live, and has spent the last 30 years working as the chief negotiator for the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations in treaty-making.

“So, she’s dedicated her life to getting our land back, even though she might not be around to really benefit from that. It’s always been a very noble thing for me to comprehend,” Hemphill said.

Colleen’s voice shares a grounded, warm tone in the film, and “the other thing is she's just tough.” Hemphill explains a humorous scene where she’s doing karate, giving out her names.

“She's a 70-year-old ‘Nakwaxda’xw Elder who's a black belt, and she’s trying to get our land back. And anyone who knows her just falls in love with her because she's so warm and gentle and smart. She’s just cool.”

Hemphill was called to the film-making path early, with a media arts program coming to his elementary school when he was in Grade 2.

“They brought in film professionals and really big cameras, and they had us interviewing Elders and using the cameras at a very young age. And I remember saying to the teachers that I was going to be a director when I grew up.”

He grew up seeing the films played at community events, showcasing the work by the students and teachers.

“That culture of creating films and sharing films was just there from a pretty early age. So it didn't seem inaccessible to me. It seemed like a thing that was good to do.”

Art has always been something important to honour with Kwakwaka'wakw culture being so rich in art and artists. Even when he was still learning technical skills and honing his craftsmanship, Hemphill has “always personally been very assured and in touch with my spiritual side, in terms of accessing that for art.”

In addition to claymation and filmmaking, Hemphill is also a recording artist working on a record to release next year.

Completed in fall 2022, Tiny is already making the rounds of the festival circuit. Last week it won the Audience Choice Award at the Salt Spring Film Festival. Next month Tiny will be at the Dreamspeakers Indigenous Film Festival in Edmonton, which runs from April 19 to April 23.

Hemphill hopes audiences leave the film with “a physical reminder of a slower lifestyle that could be integrated with nature and be more spiritual and meditative.”

Never miss a Windspeaker article. Subscribe Today to our new Windspeaker Newsletter!

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.