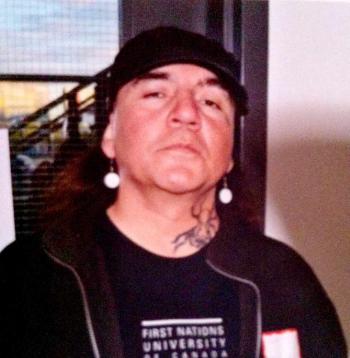

Image Caption

Summary

By Andrea Smith

Windspeaker Contributor

Saskatoon, Sask.

An ex-gang member living in Saskatoon has made his way through university.

Stacey Swampy spent 30-years in some kind of government institution or another, including foster homes, as a result of Child Welfare involvement, young offender’s centers, and provincial and federal prisons.

On June 16, he will graduate from the Indigenous Social Work program at the First Nations University of Canada Saskatoon Campus.

“I’m a social worker now… I help men and women in their struggles with addiction. I’m going to graduate this summer, and I’m doing my practicum at Royal West School,” said Swampy. “My goal is to go back into the system and help my brothers and sisters in jail,” he said.

Swampy is originally from Maskwacis in Alberta. He spent his young years there, witnessing various family members abuse alcohol—including his parents—and witnessing severe violence between family members and members of his home community, he said.

Swampy believes at the heart of his struggle, as with many First Nations youth, was a lack of love at home, and a lack of positive role models.

“My dad passed away when I was 13. When he passed away I lost that role model, so I started looking for role models. And I looked at these guys coming out of the system... They were in good shape, they had tattoos, people respected them, and a lot of women chased them,” he said. By “system,” Swampy means prison, and the men he was idolizing were gang involved.

After years of being involved in that type of life himself, Swampy’s pivotal turn-around point came after he beat up his own uncle. His “higher-ups” (in the gang) gave him orders to take the clothing from a man who was dressed nicely. Only when Swampy approached the man, did he realize it was his uncle. The two chatted for a short time, then Swampy went to leave but asked his uncle for his clothing first.

“I said ‘Uncle, I need that hat, those clothes that you’re wearing... And then he and all the guys he was with were all laughing. And they looked at me, but I wasn’t laughing. Then I hit him, and beat him up. And I felt ashamed for days. I decided I didn’t want this life anymore,” said Swampy.

That was around 2004, and though he is now fully recovered, the road wasn’t easy. A lifetime in-and-out of institutions of any kind creates its own challenges, but Swampy also had drug and alcohol addictions to deal with, addictions he attributes to grief he was carrying, stemming all the way from childhood.

Swampy credits the Elders he talked to while incarcerated with giving him his first push towards “cleaning his own house”. Elders who inspired him so much he would now like to work alongside them.

“I took down all the walls, and I trusted the Elders. They showed me this beautiful way of life, and I haven’t looked back since,” he said.

“I call myself a helper. I carry a pipe. I carry my bundle. I sing songs. I do everything. I went from being a gang member, drug addict, a jailbird… To becoming a Sun Dancer, a Powwow dancer, a social worker, and a helper for the people… I changed my life,” said Swampy.

Swampy is also involved with a program called Str8 Up in Saskatoon. It’s a gang exit strategy program. Swampy first enrolled in 2007. At that time he was using their services to help him exit the life, such as helping him find ID, treatment programs, and access other resources he needed to become independent.

The program played a key role in helping him, and because he has done work on himself, the Str8 Up team now includes him as a support person for others.

Stan Tuinukuafe is a co-founder of the program, along with Father Andre—a Catholic Priest who, Tuinukuafe says, was helping people with few resources, sometimes using his own vehicle as a mobile office.

Tuinukuafe paired up with him a few years ago, to solidify the program, and offer help to more to recovering gang members.

“Our full name is Str8 Up Ten Thousand Little Steps to Healing. We got the name because when we were coming up with the name, we didn’t want something like ‘anti-gang strategy,’” said Tuinukuafe.

“This guy was writing Father Andre from jail, and he would end it with Str8 Up. That’s how he signed off. And we thought, well you need to be Str8 Up to get better, you know,” Tuinukuafe said with a laugh.

The Str8 Up team created a four-phase model of what it looks like when someone exits gang life, to help people understand where they are in their recovery. Someone like Swampy is in the stabilization phase, which means he is basically recovered, and living a relatively normal, stable life.

The other three phases are: the Decision-Making Phase; the Transition phase; and the Transformation phase.

Tuinukuafe agrees with Swampy, that the road to recovery isn’t easy; but it can be done, he says. He points to Swampy as evidence of this.

Tuinukuafe admits, however, he and Father Andre’s approach is more hands-off, which speaks to just how strong Swampy’s own resolve to change was.

“Our job is not to walk in front of people pulling them, or behind them pushing them… Our job is to walk beside them. When they fall, we just wait for them to get up, and then we keep walking,” said Tuinukuafe.

“When I meet an individual, we talk about what they need to do. If they don’t do it, that’s on them,” he said