Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Last week, Ontario asked the Supreme Court of Canada to issue declarations of principles that must be met—“consistent with the honour of the Crown” —that would provide direction to the province as it negotiates augmented annuities with the beneficiaries of the Robinson treaties.

“The declarations have value…We’re here for that guidance. We’re here for the proper interpretation so we have a platform to proceed ahead and that will achieve reconciliation,” said Peter Griffin, legal counsel for Ontario.

The promise of augmentation of the annuity is unique to the Robinson treaties, signed between the Crown and the Anishinaabe of the northern shores of lakes Huron and Superior in 1850.

At issue before the court on Nov. 7 and Nov. 8 is the interpretation of the treaties and, specifically, whether annuities are paid to individuals or whether to the collective.

The two treaties, the Robinson-Huron Treaty and the Robinson-Superior Treaty, saw territory ceded to the Crown. In return, the Anishinaabe would receive a payment in perpetuity that would increase as long as the Crown did not experience financial loss from having that land.

In 1875, the annuity was increased to four dollars per person. In 1877, the Huron and Superior chiefs petitioned successfully for arrears on the increase. They argued that economic conditions had been favourable, and the increase should have already occurred.

The annuities have not changed since. The Huron and Superior beneficiaries initiated separate legal actions against Canada and Ontario seeking to have the annuity reset and compensation for the stagnant annuity amount since 1877.

The legal actions were tried together under the Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 and split into three stages. The Robinson-Huron Treaty Litigation Fund (RHTLF) represents the 21 Anishinabek Nation beneficiaries.

Last week’s Supreme Court of Canada hearing on Ontario v. Mike Restoule et al. (Restoule is the chair of the RHTLF and a plaintiff) was in relation to the first two stages. At the first stage, the treaties were interpreted, and at the second stage, the defences of the Crown were addressed.

At the third stage, compensation would be determined.

At trial, the Ontario Superior Court concluded that the Crown had a mandatory and reviewable obligation to increase the treaties’ annuities when economic circumstances so warranted. The annuities should reflect a fair share of the value of the net Crown resource-based revenues generated from the territory.

Ontario appealed the 2018 trial decision. Canada did not. In 2021, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld the lower court’s decision.

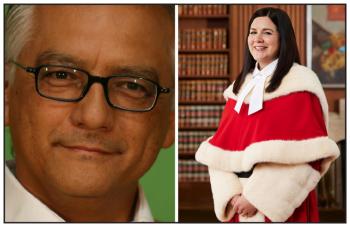

Justice Michelle O’Bonsawin, a member of the Odanak First Nation and the only Indigenous member of the Supreme Court of Canada, asked Griffin to explain how Ontario had met the obligations of respect, responsibility, reciprocity and renewal to the treaty holders.

Griffin conceded that Ontario had failed in its obligations and said he was not asking “for absolution in the respect to history.”

However, he was asking for a “correct interpretation of the treaty.”

Griffin argued that there was only one annuity included in the treaty and it was paid to individuals.

However, David Nahwegahbow, co-counsel for RHTLF, said Ontario’s interpretation of the treaty “leaves nothing for collective purposes… (which is) at odds with the nation-to-nation nature of the treaty relationship.”

It comes down to, said both Nahwegahbow and Griffin, how the text of the treaty is weighed against the context of when the treaty was signed.

Nahwegahbow said the context includes Anishinaabe law, perspectives and principles, an interpretation that was recognized by the trial judge. He urged the Supreme Court to agree with her “findings of fact” which flowed from documentation and testimony.

Catherine Boies Parker, co-counsel for the RHTLF, however, told the court that Ontario was foot-dragging to the compensation stage by asking the top court for the treaty interpretation and principles declaration. Compensation was well past due for the breach of annuity provisions over 170 years, she said.

“The Crown doesn't get to ignore its treaty obligations for 170 years and then come and say, ‘Just give us a bit more time’, she said. “I think it's important that this court reject that approach because this idea that this is a uniquely difficult thing for the courts to do or something, it really risks putting these treaty rights back into the realm of a political trust.”

But the top court’s interpretation could be the difference between Canada and Ontario paying $10 billion in retroactive compensation or as much as $126 billion.

Harley Schachter, legal counsel for plaintiffs Red Rock and Whitesand First Nations, Robinson Superior Treaty signatories, said the court needed to “get on with interpreting a quantification of loss” based on the promise that the annuity would be increased if the economic conditions on the land made it possible.

Schachter said Ontario is arguing the province realized a loss up to $11 billion over the last 170 years, in the case of the Robinson Superior beneficiaries. However, Schachter said the plaintiffs’ own Nobel-prize winning economist suggested a gain of $126 billion “at the top end” as fair compensation.

Complicating matters is that the trial court has already advanced to the compensation stage without the top court’s interpretation, which is baffling to the Supreme Court of Canada justices.

There’s a “logical sequence” that has not been followed, said Justice Malcolm Rowe. That sequence of events would have seen a decision made on the interpretation of the treaty, then the nature and extent of infringement, which would be followed by the remedy of financial compensation.

“The only sensible thing to do here is for the (trial) judge to wait. I find it extraordinary that the judge is contemplating, ‘Don't worry about the Supreme Court of Canada. I'm just going to render my decision.’ I mean I find it baffling. Almost unbelievable, frankly,” said Justice Rowe.

The result, he said, “may be a complete mess for everyone. Just a situation of chaos in which no one knows what to do next or what the status of the decision is.”

Justice Mahmud Jamal was unsure that a court was equipped to make such a determination on money.

“If the treaty had a formula, it would be one thing. But it doesn't have a formula. It says ‘Her Majesty's Graciousness.’ So we're left without the judicial tools to fix what the number is,” said Justice Jamal.

“Her Majesty’s Graciousness” is the phrase used to refer to the mechanism by which the annuity increases.

But there has been movement on determining the value of the compensation owed and the respective liabilities of Canada and Ontario.

The Robinson Huron beneficiaries have negotiated a $10 billion out-of-court settlement, to be split evenly between Canada and Ontario. The details of that settlement are confidential and the settlement has not been finalized. The Supreme Court’s ruling will not impact this compensation.

Meanwhile, the Robinson Superior beneficiaries concluded their legal recourse in the lower court for Stage 3 in September. They are now awaiting the decision of the trial judge. The trial judge has not committed to waiting until the Supreme Court delivers its decision.

Boies Parker pointed out that the Red Rock and White Sands First Nations case began in 2001, while the RHTLF case began in 2014, so the compensation issue is delayed justice.

“We're losing (our Elders) and they haven't had an opportunity to see the results of this court case. And I think it was important that this difficult issue of compensation start to be addressed. Maybe there will be some ways in which it is not consistent with this court's ruling and then that will have to be addressed. But it could be that even if you choose a different interpretation than (the trial judge) chose that it isn't actually going to affect the assessment very much,” she said.

The Supreme Court also heard from 19 interveners, including legal counsels for the Assembly of First Nations, a coalition including the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc., Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, Kee Tas Kee Now Tribal Council, Athabasca Tribal Council and a number of individual and joint First Nations.

Chief Justice Richard Wagner said the court would take the case under advisement.

Windspeaker is owned and operated by the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta, an independent, not-for-profit communications organization.

Each year, Windspeaker.com publishes hundreds of free articles focused on Indigenous peoples, their issues and concerns, and the work they are undertaking to build a better future.

If you support objective, mature and balanced coverage of news relevant to Indigenous peoples, please consider supporting our work. Whatever the amount, it helps keep us going.