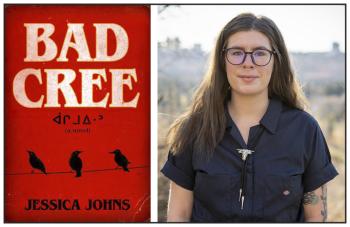

Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

In writing her debut novel Bad Cree, author Jessica Johns did exactly what her characters did: They threw off the constraints of colonial thinking and embraced their Cree traditions.

The short story of the same name which spawned the novel are both centred on the dreams of main character Mackenzie. While the short story is more mystical in nature, the novel turns that mysticism up a notch and launches into a taut fantasy horror.

It takes Mackenzie a while to embrace her dreams and understand their importance. But not so for Johns. She had been challenged by her instructor during a creative writing course as she was finishing her master’s degree in fine arts at the University of British Columbia. The instructor told her that dreams would “bore the reader.”

“It was really disillusioning to hear that something that I knew to be very valid, like listening and paying attention to dreams, was, in a colonial framework and in a colonial kind of mindset, frowned upon and advised against,” said Johns, a member of the Sucker Creek First Nation in Alberta.

It didn’t “sit right” with her and she continued to think about it “and I just decided instead of listening to that advice I was going to rebel against it in my own way.”

Her poetry chapbook, “How Not to Spill,” which preceded the two versions of Bad Cree, is filled with dreams and dream imagery as well.

“I just knew that how valid dreams were to me, that they were also to other people and…I knew that people would identify with dreams and dreaming and the validity of them so I really wanted to write that truth into the book,” said Johns.

And she wasn’t wrong. Johns embraced her culture to write a novel that resulted in a bidding war between three publishing companies.

Dreams have a deep meaning in Bad Cree. On the surface they act as the catalyst for Mackenzie to leave Vancouver. Her nightmares are disrupting her life and she returns home to High Prairie in northeastern Alberta to reconnect with her family. In this way, the dreams explore at various levels what Indigenous people in Canada have lost.

Johns points to Mackenzie’s reticence to even discuss her dreams with the women members of her family as a tangible impact of colonial violence. It is a reticence shared by her family members.

“Colonialism and the violences of policies against practising language, practising ceremony, has, for a lot of Indigenous people, imbued a lot of shame in themselves and in the things they inherently know and can do because they’ve been told for generations and generations that we’re not allowed to practise these things. They’ve been really suppressed,” said Johns.

In Vancouver, Mackenzie has a connection with Joli, who is Squamish, but Mackenzie is still lonely because she doesn’t have a connection to her own Cree cultural knowledge as she is isolated from her family.

“Mackenzie is disconnected from community in both ways. When she’s living in Vancouver, she’s not a really great community member. She’s not really engaged in the community around her...When she goes home, she’s not really living in a great way there either. She isn’t very forthcoming with her family…so I think it was important to show (that) even though she was physically in Vancouver and physically in High Prairie in Treaty 8 territory, she was still disconnected because she wasn’t giving her energy to the community members she should be in good relationship with,” said Johns.

Turning the short story into a novel gave Johns the ability to develop the characters fully and to draw out their motivations.

Mackenzie is “a very avoidant person. She doesn’t accept help or doesn’t accept love very easily. It made sense for the novel to be able to really take my time with that and really lean into that,” said Johns.

As much as Johns employed dreams to tell her story, she also employed a legend that is shared by numerous First Nations’ cultures. As soon as Johns knew the short story would become a novel she made the immediate decision to go with a “greater force that was descending upon this family.”

The greater force is also representative of and created by the greed in today’s world, which sees landscape changed through “the violence of land extraction and continued settlements and displacement of Indigenous people from their land,” said Johns. Mackenzie returns home to find the booming oilfield industry gone. Now, the town is quieter, stores are closed, and the land has been bled.

“Those really go hand-in-hand with the greater force that they deal with and the rest of the changes she sees in her family members and how she comes to terms with all of it,” said Johns.

Johns pulled on a number of versions of the legend and took “creative liberties” similar to other Indigenous authors to embellish the “greater force” (which we won’t name here), including its ability to infiltrate dreams as “that just worked into the story so that’s what I used.”

Aside from some heart-stopping moments that will thrill readers, Johns said she hopes something more will resonate.

“I think it’s a success if people feel like they are in some way deemed seen or represented in a good way. I think the biggest thing that I hope people see, I really imbued a lot of aunty love in this and how powerful and beautiful and big the love (is) between aunties and family, whether that is blood relation or not,” said Johns. “I hope that they see a powerful love and connection with family and aunties in the book.”

As for the title of the novel, Johns said many Indigenous people feel that being separated from their culture, ways and traditions makes them “bad.”

“I think (Mackenzie) initially thinks that…and it’s not (true). Because it is not her fault that she doesn’t know her cultural knowledge that she has every inherent right to know. It is a shame that belongs to the Canadian state. It’s a shame that belongs to assimilation tactics and violences that again have been happening to her family for generations… (and) she really has to shed that idea (because)…she’s Cree no matter what,” said Johns.

Bad Cree, published by HarperCollins Canada, is available now in bookstores and online.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.