Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Scooped away from her mother as a toddler. Adopted by a white family that starved her and locked her in her bedroom. Returned by them to a group home for troubled children after she ran away. Bounced around from foster home to foster home to foster home in seven years. Aged out of the childcare system with no guidance or help.

Tragically, this story – or a variation of it – is the common childhood of an estimated 20,000-plus Indigenous children taken from their parents in what became known as the Sixties Scoop, a practise of the child welfare system which lasted from 1951 to the mid-1980s.

It’s because of this shared history that Christine Miskonoodinkwe Smith thought it important to tell her story.

“A lot of people that have struggled with the Sixties Scoop, being in child welfare, they feel alone. I know I felt alone, especially when I aged out of care and … I didn’t have family. A lot of Sixties Scoop individuals struggle with the fact they don’t have family,” said Miskonoodinkwe Smith, who is from Peguis First Nation.

She describes herself as “a Sixties Scoop survivor, a Bill C-31 status Anishinaabe woman and a daughter of a Saulteaux mother and a Cree father. I was born in Winnipeg forty-plus years ago.”

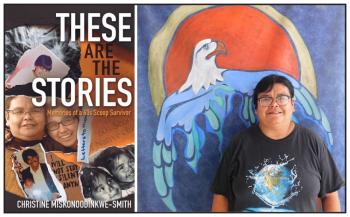

These are the Stories: Memories of a 60s Scoop Survivor is the collection of personal essays that Miskonoodinkwe Smith wrote over a period of 20 years or so. That she had written so many essays about her time in the system was a surprise, she says.

But it’s “amazing” to see them in a single collection.

“I was also nervous at the same time because I was just like, ‘Oh my God, I did it.’ Because I’ve been wanting to write a book for years,” said Miskonoodinkwe Smith, who in 2016 was accepted into the Aboriginal Emerging Writers Residency program at the Banff Centre.

Her storytelling is not linear, bouncing from one place in time to another.

“A lot of it has to do with the way First Nations people tell stories. We don’t necessarily have a beginning and then an end. A lot of stuff flows in a circle, very much like the Medicine Wheel. At least that’s what I believe,” she said.

There’s also repetition, which led to deeper understanding for her as she retold parts of her story as parts of different settings.

“A lot of the stuff that I wrote, I did repetition because everything was mixed in with each other. It’s a good way to keep memories alive and keep your truth going,” she said.

Miskonoodinkwe Smith adds that having to edit her work also caused her to dig deeper and, in doing so, other aspects of her story resurfaced.

“Christine’s stories are sometimes triumphant, sometimes traumatic, often painful to read, and courageous of her to share,” writes Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm in the foreword.

“There are gaps in her story. Or rather, there are gaps that are part of the story,” continues Akiwenzie-Damm.

In the preface of the book, Miskonoodinkwe Smith explains those gaps are caused by her “struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety (so) my recollection of some dates and details in my life are a bit foggy….”

Miskonoodinkwe Smith and her sister were taken from their mother Anna Smith when they were toddlers. Anna was a residential school survivor.

In her mid-30s Miskonoodinkwe Smith found her mother.

“There are no words to explain the feelings that coursed through me when I saw her for the first time,” writes Miskonoodinkwe Smith, who spent three days with Anna that first time.

They had a brief relationship in which time Miskonoodinkwe Smith learned how difficult her mother’s life had been and the struggles she had and continued to have. She also learned her mother was resilient. Just under five years ago, Miskonoodinkwe Smith’s mother “began her journey to the spirit world.”

Miskonoodinkwe Smith’s life has also been a journey, one that saw her decide to undertake higher education in her 30s, graduating from the University of Toronto with a specialization in Aboriginal Studies in 2011. She earned her Master’s in Education in Social Justice in 2017.

Today she lives in Toronto and works as a data coordinator for the Miziwe Biik, an Aboriginal employment and training centre.

“I’m a lot stronger than I was. I’m more confident than I was. I’m successful. I have a hard time talking about myself in a positive way that way, but that’s just residual negative thinking that I had in the past,” said Miskonoodinkwe Smith.

She has triumphed over those who thought she would never live past her 25th birthday.

“I think that’s the fighter in me,” she said.

Writing her story is not only about letting other Sixties Scoop survivors know they’re not alone.

“In order for the government and mainstream public to understand the impact of how the Sixties Scoop affected Indigenous children, and still has an impact to this day, I find it important to tell our stories, because then it will be hopefully understood that there are many children who were impacted in one way or another,” she said.

“With this said, true reconciliation is when our stories are heard and our histories are understood so that the government and mainstream public will stop entertaining the racism, discrimination and stigmas against the Indigenous populations of Canada and elsewhere.”

These are the Stories: Memories of a 60s Scoop Survivor was published by Kegedonce Press in December 2021. It is available through the publisher, Amazon, Indigo and local bookstores.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.