Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

For Danita Bilozaze of Łuechok Túe, using her family’s original Indigenous name is an essential part of preserving her connection to culture. So Bilozaze undertook a mission to get her Indigenous family name on all of her official identification, an effort that took many difficult months.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 94 Calls to Action were adopted by all forms and levels of government, said Bilozaze.

“However, I learned with my name reclamation experience that there are racist laws and lack of policies in place” to support the call to allow Indigenous names to be restored for people’s use.

Bilozaze is of Denesųłįné descent, and she grew up in a cultural home where her grandparents spoke their language to her.

Our names are linked intrinsically with our identity, Bilozaze said, giving her own surname as an example.

“Bilozaze means ‘the makers’.” To this day her family members are artists involved in a wide range of creative expression, including beadwork and visual arts.

“The major hurdles that had to be overcome were around education. Ironically, that is the tool that was used to assimilate Indigenous people. To this day there's a lot of gaps in people's knowledge around truth and reconciliation,” Bilozaze said.

On May 26, Bilozaze received a letter from Service Canada that said her passport name had been officially changed, and that her work had had wider impact.

It was a bright spot in a long process plagued by hurdles and tears.

Erasure

For two hundred years, Indigenous names have been erased, Bilozaze explained. Indian agents, census workers and residential schools staff misspelled names, substituted biblical names, or even gave people the Indian agents own surnames.

These actions were deliberate attempts to systematically erase Indigenous culture and identity.

Assimilation was the mandate and taking away names while forbidding Indigenous people the use of their ‘old’ names was part of that campaign.

During the nine-months long process to reclaim her original family name on official documents, Bilozaze had moments when she felt like giving up in the face of layer after layer of bureaucracy.

Bilozaze is an educator and had the foresight to send links and resources to offices and ministries she would need to work with in an effort to educate them on the issue.

The first step in changing her name began with fingerprints with local RCMP.

Despite the prep work Bilozaze sent, the clerk had never heard of TRC Call to Action #17, which would enable the reclamation of an Indigenous name, nor did any of the other staff present.

This pattern of officials’ lack of knowledge repeated itself at every step of her name change process over multiple agencies and ministries.

Reclaiming Indigenous names should be a celebration, Bilozaze said. Instead it was a lot of work with disheartening moments of replaying the same requirement to educate, inform, and push.

Once she realized the agents she was dealing with had no idea about this Canadian history, “I was then dealing with their feelings and emotions around it, rather than what I was there to do. It's really supposed to be a celebration, reclaiming our name, but it wasn't.”

Each document has fees involved, and under the Calls to Action, all of these are to be waived.

“It was pretty insulting to hear ‘We realize that you're reclaiming your Indigenous name that was taken from you by the government and churches and government agencies. And now we're going to charge you thousands of dollars in fees in order for you to reclaim what is rightfully yours to right these wrongs’.”

It was when she needed to update her home’s property title that the full weight of the task hit home.

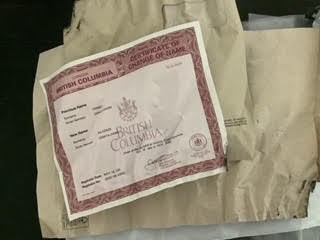

Part of the process requires sending original identification documents. She had one piece, her brand new birth certificate, which she had struggled mightily to get.

Documents sent to change property title are normally kept during the name change application and then returned. Bilozaze sent hers to the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, the ministry responsible for British Columbia’s land title system.

Bilozaze’s new birth certificate was sent back from the ministry after three months. It had been crumpled, torn and burned.

“Is this what reconciliation looks like in Canada,” she wondered.

Names Matter

Her relations and ancestors inspired her to persist in the struggle.

“I kept those who came before me in mind, energizing me to push for the change in laws and policies.”

Bilozaze has strong communication skills as an educator, with 10 years with School District 72 on Vancouver Island, B.C. as a District Indigenous Culture Teacher at Southgate Middle School. The name-changing process tested that skill set and her patience, she said.

It was Bilozaze’s grandfather Ts’inaze, who encouraged her to pursue post-secondary education.

Ts’inaze, means ‘survivor’ in English. An ancestor was an infant who was the last surviving community member in a village and was adopted by an older couple who gave him the name Ts’inaze. Her grandfather’s English name was John Blackman.

“John Ts’inaze was my first teacher, and he had the most influence over me. And before he transitioned to the next place, he made sure my aunty told me I am his heart. So, when I am guided, it is my grandfather John who has given me the best advice and still guides me from the next place.”

Bilozaze’s mom, Albertine Finney (Bilozaze), did not marry her father because of the rules under the Indian Act. If she were to marry a non-Indigenous man and if their children took his name, they would all be denied tribal membership and would have been required to leave their home community.

“My mom decided to hold off marrying my dad until 1977,” said Bilozaze. “My older sister and I were protected because of her choice to not marry my dad until much later. My little sister, who took my dad’s name at birth, was not considered a tribal member until they changed this under Bill C-31, which did not happen until the late ‘80s.

“How can one family be faced with so many divisive rules? We will never have equality until the Indian Act is dismantled,” said Bilozaze.

The hardest part was not feeling heard, Bilozaze said of the name changing process. She thought of all the family and community members who might have just given up.

“There were many times I wanted to give up.” But Bilozaze had her 15-year-old daughter at her side as a motivation.

“My daughter's watching my every move. And she was with me every step of the way too. So the day my identity was returned, crumbled and burnt and just terrible, she was there with me while I was crying. At the passport office, she was there, watching me say ‘there has to be a better way, and we're going to find it’.”

The Calls to Action aren't something that were created yesterday, said Bilozaze. This has been going on for six years.

“When government words and actions do not line up, this is where allies need to shine a big light to push for change,” said Bilozaze.

Tools should serve instead of create more hurdles

When it came to her passport, Service BC suggested Bilozaze go to Service Canada’s Victoria office to have this special case handled properly.

When she arrived, two layers of security told her she needed an appointment due to COVID-19 protocols. She told them her situation and was permitted in.

It was a completely empty office, yet a clerk told her repeatedly she needed an appointment.

When Bilozaze told her full story, the clerk pointed at her screen, which said ‘Appointment Required’ and flicked the passport application form back. It was supposed to be mailed, Bilozaze was told.

Refusing the clerk’s dismissal, Bilozaze asked a guard if she could speak to a manager. Acting Team Leader Samantha MacPhail gave her full attention to Bilozaze’s application.

That supervisor’s support illustrated the importance of allyship to collectively move our society forward, said Bilozaze.

“I received an email saying because of my ‘action and bravery, Indigenous Canadians across the country will no longer walk into our offices and be met with a non-answer’.”

“Service Canada told me, ‘we have the tools we need to be able to serve, and we will do so’.”

On June 14, the federal government announced that Indigenous people can now apply to reclaim their traditional names on passports and other government ID.

Indigenous Services Canada Minister Marc Miller said the announcement applies to all individuals of First Nations, Inuit and Métis backgrounds and could affect hundreds of thousands of people who want to reclaim their identity on official documents.

All fees will be waived for the name-changing process, which pertains to passports, citizenship certificates and permanent resident cards.

Bilozaze said she had petitioned Marc Miller for support during her name-change ordeal, and received no response at all from the department.

Miller’s statement today leaves Bilozaze wondering if Samantha MacPhail will receive due recognition.

"It was the work of Samantha MacPhail who was spurred on by my story and doing what was right," Bilozaze said.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action #17 says “We call upon all levels of government to enable residential school Survivors and their families to reclaim names changed by the residential school system by waiving administrative costs for a period of five years for the name-change process and the revision of official identity documents, such as birth certificates, passports, driver’s licenses, health cards, status cards, and social insurance numbers.”

Bilozaze said Canada Passport asked her permission to use her story for their national training, “to bring awareness to the changes that need to be made to meet the Calls to Action.

“And to bring to light the work of reconciliation that all Canadian citizens share responsibility in.”

Bilozaze is clear that the education and heavy effort required must be shared by all Canadians, not left to Indigenous people to shoulder.

The TRC says, “Together, Canadians must do more than just talk about reconciliation; we must learn how to practise reconciliation in our everyday lives—within ourselves and our families, and in our communities, governments, places of worship, schools, and workplaces. To do so constructively, Canadians must remain committed to the ongoing work of establishing and maintaining respectful relationships.”

“Our reconciliation work is around healing, for non-Indigenous people it is educating themselves and being allies in making the policy changes.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.