Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

New art books are being released this fall that showcase the works of legendary Northwest Coast First Nations artists.

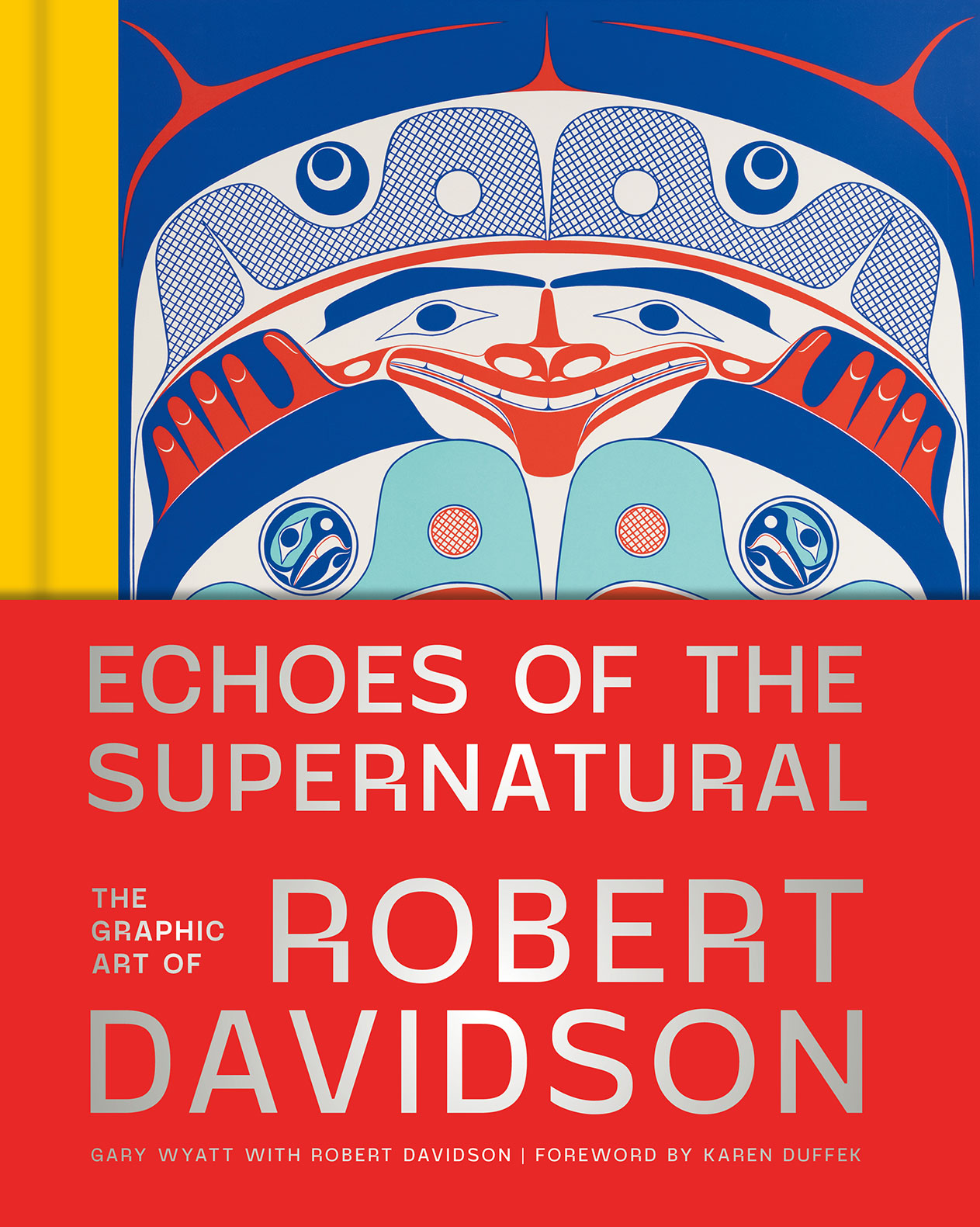

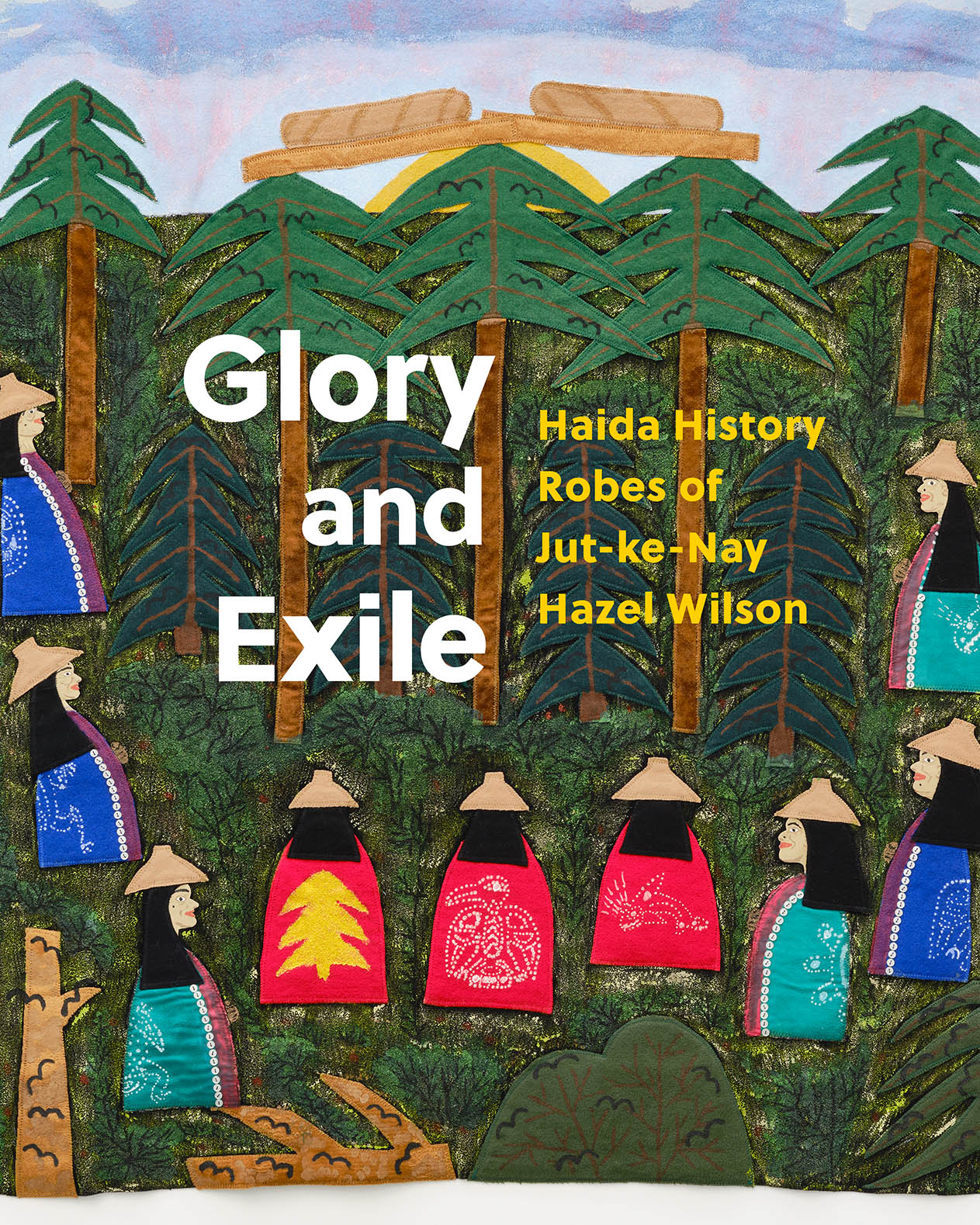

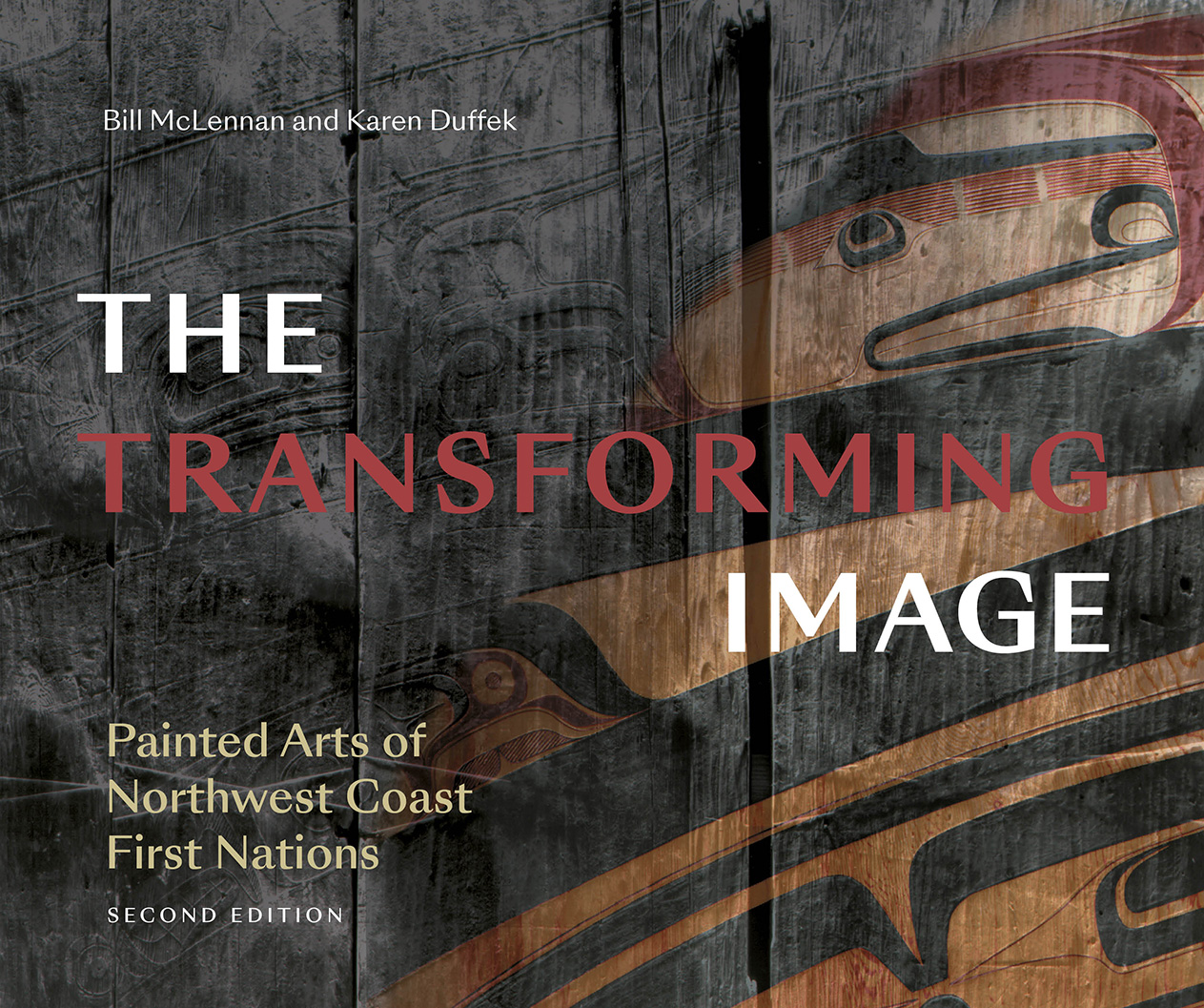

Echoes of the Supernatural: The Graphic Art of Robert Davidson takes us on a tour of Davidson’s half-century of print works. Glory and Exile: Haida History Robes of Jut-ke-Nay Hazel Wilson features a series of 51 large story robes created by Wilson, which tell the story of Haida life since contact with Europeans. And The Transforming Image: Painted Arts of Northwest Coast First Nations is an art book first published in 2000 and now being released in its second edition. According to Davidson it is “an incredible archive of painting for Northwest Coast artists.”

Gary Wyatt is an artist, curator and appraiser based in Vancouver and the author of Echoes of the Supernatural. He has worked with and represented Davidson for more than three decades, so he had a very good understanding of Davidson’s prints. Just before COVID, Wyatt was updating Davidson’s price list and a thought came to him.

“I asked him at that time why no one had ever updated the book. There was one done in 1979 by Hilary Stewart called Robert Davidson: Haida Printmaker. It’s an historic book; it’s quite famous. But realistically it’s been out of print for pretty much 40 years,” Wyatt says. “And his answer to that was, ‘nobody’s ever asked.’ So I asked. And that was it.”

Wyatt and Davidson spent two days pulling out every single print from Davidson’s studio.

“So it’s not like I had to travel around the world to bring them all together,” Wyatt says. “We just lined them up and did all of the documentation and photography. And on top of that, he already had the photo files of paintings and everything else.”

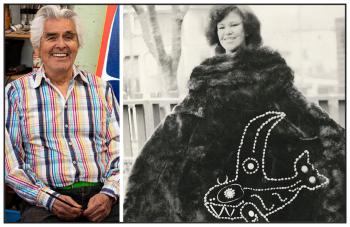

Davidson has been creating art since the age of 17. Now nearing his 76th birthday, he is known for his masks, jewellery, sculptures, totem poles, painting on different mediums, such as spruce hats, baskets, drums, as well as canvases, and of course his graphic prints. This book focuses on painting and prints and will be released on Oct. 18.

“For this book release we have people coming from all over and it’s just because they have such incredible respect for him,” Wyatt says. “He’s a super nice guy. He’s very level. People like him. I mean that doesn’t have to be a criteria for an artist. You can hide in your garret and make paintings and you can be incredibly hidden away, which does not make you a bad artist and can even make you a good one. But he’s one who can spend time in the studio making work, but when he comes out he can stand in front of thousands of people and talk, and he can be in a crowded room and just totally own it.”

Robert Kardosh is the owner and director of Vancouver’s Marion Scott Gallery and had worked with Hazel Wilson for many years until her death in 2016. The gallery is the home of her numerous story robes. Kardosh is the driving force behind compiling this new book, spending hours reading Wilson’s explanations for each robe, deciding the best order to display them, and writing an essay interpreting the project.

“My essay kind of interprets the whole narrative. She has texts which are the narrative, so the main part of the book is her voice, her words with her text which accompany each of the robes,” Kardosh says. “But I decided that it needed a certain amount of interpretation.”

The book also includes a wonderful biographical sketch of Wilson and her life, written by Robin Laurence; a personal memoir by her daughter Dana Simeon; a powerful forward by Nika Collison, director of the Haida Gwaii Museum; and an afterword by Wilson’s brother Allan Wilson, chief of the St’langng Laanaas clan.

The family’s original West Coast village hasn’t been in existence for a couple hundred of years. “It was one of the villages that they had to abandon when smallpox was spreading and decimating the population there,” Kardosh says.

In fact, this series of robes tells this story.

“It’s actually a contact narrative,” Kardosh explains. “It's about the whole 300-year history of contact. She starts it in the time before that period as a way to set the stage for the changes that would occur, but rather than a whole history of the Haida, it’s a contact narrative from the late 1700s until the middle part of the last century.”

When Wilson began bringing the robes to the gallery in 2006, they didn’t realize at the time she was creating a new series and originally a few were sold to private collectors. But the gallery is home to 43 of the robes and all 51 are displayed in this book, which is quite a feat as this would not be possible at the gallery for the simple issue of spacing. The book was released Sept. 27.

“Hazel very much wanted this work to be seen and to be appreciated, but also she wanted her messages and her themes to be received, and one way of doing that is to publish a book, so it gets into many hands,” Kardosh says.

“She’s taken this button blanket form, which has been standarized over the decades, and she’s totally opened it up and done something completely different with it. And the idea of sequencing these things together to tell a whole narrative is also very revolutionary. So she’s taken that form and given it an entirely new life and dimension.”

Twenty-two years after its initial publication, The Transforming Image is still very much in demand.

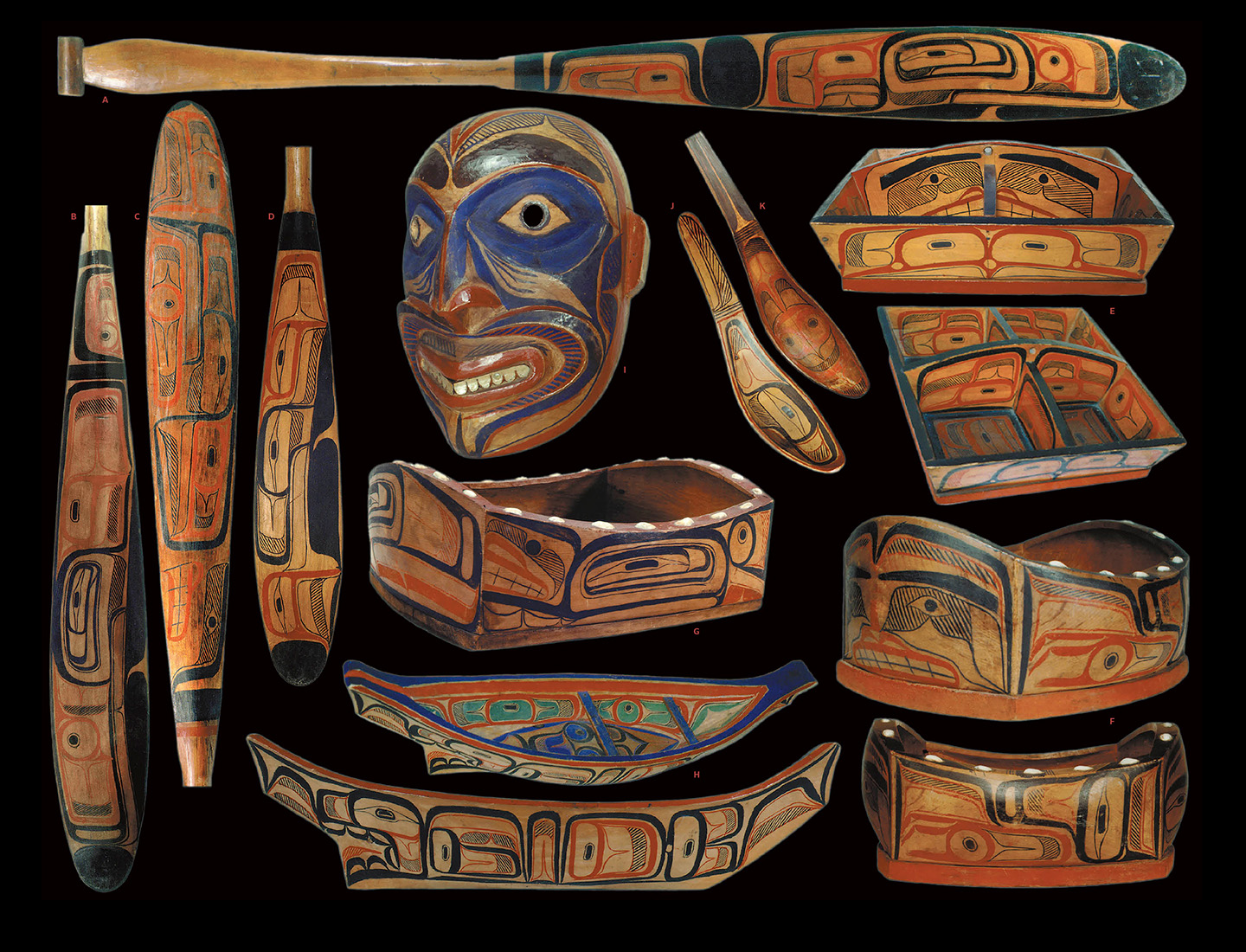

“Most importantly by First Nations artists of the Coast who want to keep it handy in their studios and on their work benches as an important reference and resource,” says author Karen Duffek. “It has hundreds of infrared photos of historical Northwest Coast painted compositions—paintings on bentwood boxes, chests, and drums that, as Indigenous belongings in museum collections spread far and wide, are otherwise not easily accessible.”

Duffek says the original book has been almost impossible for people to get hold of for more than a decade. So the Doggone Foundation in Montreal and Yosef Wosk provided funding in honour of Bill McLennan, Duffek’s original co-author who died in 2020, to make the book available again.

“Preparing the reprint turned out to be way more work than I thought it would be—renewing 906 photo permissions from over 50 museums and archives plus tracking down private collectors who had all allowed Bill to photograph their collections—plus, who knew that so many museums have changed their numbering systems? Lots of detail work, checking, corrections, updating, and so on,” Duffek explains.

“Some of the treasures have changed hands and had to be tracked down, and some have been repatriated in the meantime as well, which was heartening to learn.”

Duffek also took the opportunity to engage with a number of younger generation First Nations artists of the Coast who use the book and who are developing their own painting practices.

“We needed to reflect on what the book helped to set in motion, and where Indigenous community members are taking the art over two decades later—into different kinds of media, painting on cedar and on the land and on the body—researching and bringing the art home in multiple ways. So the preface to the new edition includes their reflections and where they see the art moving now, and how important it continues to be for artists and community members to have access to their ancestors’ work.”

The new edition is available to purchase Oct. 4 and embraces a context of Indigenous art that has changed quite significantly from that of its first printing in 2000.

“First Nations are leading museums into making major change around institutional control of collections, assessing what it really means to “preserve” objects and for whom, and how the belongings can return home in different ways: repatriation, access, activation inside and outside the museum, researching collaboratively to continue to build knowledge around the historical art and ensure its future,” Duffek says.

“There are many First Nations artist-scholars who are dedicated to the art and cultural practices, and who are bringing the art back into relation with the community. So in a small way, we hope that making this book available again will contribute to that important work.”