Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Vision tests bring to mind eye charts of letters on a screen running from large to tiny.

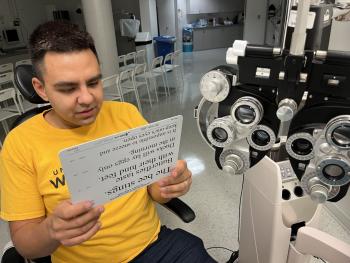

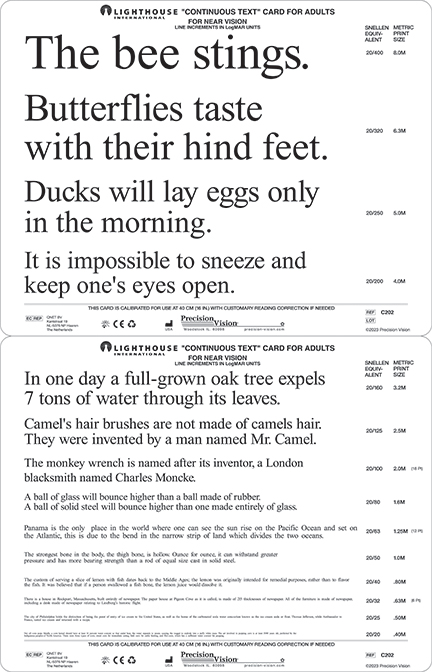

Reading cards in vision tests use more involved text. An optometrist will hand the patient in the chair the card to test near vision.

Jeremiah Hyslop of the Xaxli’p First Nation is an optometry student who worked to update the vision test cards.

Hyslop attends the School of Optometry and Vision Science at University of Waterloo. In Hyslop’s Clinical Techniques lab, the test card he was handed read “popcorn was perfected by the American Indians” and “Indian corn is used for popping.”

He was taken aback by the use of the word Indian and not Indigenous.

“I was quite shocked, to tell you the truth. I thought that it should be common knowledge by this point that that's outdated language to be using,” said Hyslop.

“And I thought, ‘of all the places where you'd want to be politically correct that in a healthcare appointment would be number one’. Unfortunately, that wasn't the case,” he said.

Hyslop told Windspeaker he was “raised to speak my truth and do my best to make change.”

“I come from a long line of very feisty, stubborn individuals, and I guess they passed that on to me,” he chuckled.

It was easy to bring this matter to his professors, Dr. Lisa Christian, associate director of clinical education, and Dr. Natalie Hutchings, associate director of academics. He had “built a trusting relationship with them,” and “felt like I wasn't going to face any prosecution if I brought it forward politely.”

That trust is key, Hyslop said.

“We need to have those trusting relationships in every single healthcare appointment of any type,” he said.

“I can think of different times when I've told my doctors about symptoms that have led to more serious illness that I wouldn't have felt comfortable telling the racist doctors. I didn't trust them,” said Hyslop.

Lived experience with racism in healthcare was a motivator for Hyslop’s pursuing a career in healthcare.

“And some of my family members, like me, had developed a general mistrust for clinicians as a result of many racist encounters.”

“I wanted to try and change that narrative,” said Hyslop. “And I wanted to increase the number of Indigenous clinicians, because in most healthcare careers there are very few, unfortunately.”

The testing equipment company that produced the reading card was immediately receptive, something that “was quite shocking to me as well,” said Hyslop.

Hyslop was expecting resistance or to hear dismissive responses such as, “‘Oh, this is how it's been for so long,’ or ‘it's too expensive to change it.’ or other excuses,” he said. “That's all that they are–excuses. But I didn't hear any excuses at all from them.”

He credits “Precision Vision for this example of cultural sensitivity, and their time in making this change to a product that hasn't been changed since the 1960s.

“They spent a lot of time, effort and money on this. Something that they absolutely did not have to do by some people's definition, but it was the right thing to do.”

Hyslop worked with Elder Myeengun Henry, Indigenous knowledge keeper with the University’s Faculty of Health to shift the language while still meeting clinical goals.

The new card reads, in part, “Not all corn pops…The art involved in popping corn is at least 5000 years old, perfected by the Indigenous peoples of North America.”

Now that the cards are revised, it’s a matter of getting them into circulation to all the optometrists who have the old reading cards in use.

“Most optometrists that I talked to have had this same card for 20 some odd years,” said Hyslop. “So it's a matter of convincing people to buy the new one. And it's also a matter of making sure distributors carry this new card, so that it's easier for optometrists to purchase.”

Hyslop said he knows one of the distributors initially “rejected carrying this new card in place of the old one, even though the old one's not being made anymore, because even though they saw the difference in wording, they said, ‘well, it's the same product’.”

Hyslop would like people to understand it is not the same product.

“How you direct your language towards different groups is really important, especially given the different settings that you're in in healthcare,” Hyslop said about cultural safety and trauma-informed care. A care professional has to meet the patient in a way that cares for his or her mental, emotional and spiritual wellbeing, as well as their physical health.

“In places where there may be emotions running high, like an eyecare appointment where you may figure out that you're going to lose your vision, it's really important that all sensitivity is taken into account,” he said.

“It might just be a word, but it's a lot more important than just a different word,” explained Hyslop.

Some people “might think it’s an insignificant thing. The Canadian legislation still uses it, for example, in The Indian Act, “but that word's not appropriate to use anymore.”

Hyslop said “most of my classmates didn't understand that this was a word that was not OK to use.” They were reciting this word when the class was using the cards to test each other.

“I'd asked a bunch of them afterwards about their thoughts,” said Hyslop, receiving responses like “‘Oh, I don’t think anything is wrong with it’.”

“I don't fault them at all for it. I think it's just a general gap in the education in Canada, which is an indication that people need to learn a lot more about us.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada