Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

The Keewatinohk Inniniw Okimowin Council (KIOC) has declared a state of emergency on health services for its 23 member Nations in Manitoba’s north.

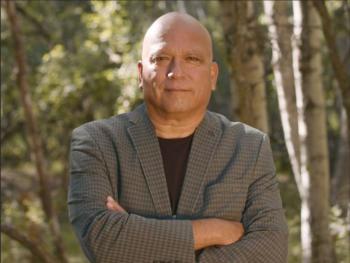

Dr. Barry Lavallee, CEO for Keewatinohk Inniniw Minoayawin (KIM), the health arm of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO), says the action was taken to address the lack of appropriate health services, which he stresses is fueled by racism and discrimination.

“When a large, well-funded system like the federal government or provincial government see that there are dire and material consequences to the lack of services in an area and does not respond accordingly except to make excuses and small patchwork (measures), this is how racism looks at a larger structural level,” said Lavallee.

The state of health emergency was declared on May 24, brought to a head with the nursing shortage that impacted the 21 nursing stations staffed by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC). There’s also a delay in medivacs because of the lack of planes and pilots, points out Lavallee.

As of May 26, however, said ISC spokesperson Nicolas Moquin in an email statement to Windspeaker.com, nursing stations are “currently operating at/or slightly below minimum staffing levels” and for the week of May 30, only one community is expected to be operating at just below minimum staffing levels.

Lavallee says ISC hasn’t made it clear to KIM what the definition of “minimum staffing level” is and there’s “no proof” to ISC’s claim.

These nursing shortages only scratch the surface of lack of support for health services experienced in the north, says Lavallee, who has held his position since 2020. The previous year he served as medical advisor for KIM. Lavallee is a member of the Métis community of St. Laurent, Man.

“A system knows that if it gave the money and did what it was supposed to do, health would improve, death rates would drop. But if I choose not to and just claim that it's too expensive, that's how racism looks,” said Lavallee.

He adds that the present state of health in Manitoba’s north was stressed even further by the coronavirus pandemic, but COVID-19 was not the cause.

Lavallee says declaring the state of health emergency is both a move of desperation and an attempt to be proactive.

The current system is not working, he says, and funding of $115 million available from the Manitoba government for health transformation in the north through more surgical units or more obstetricians isn’t the full answer.

“My argument to that is don’t even look there until you deal with racism. Because even if you infuse $115 million and you don’t change the racist attitudes of people who work in the north, not all people, it makes no difference because the only way you get a CT scan is by a physician examining you, believing you, and then ordering the test. That doesn't occur as often as it should. That's how racism looks on a one-to-one person. We see that all the time,” said Lavallee.

He adds people are continuously denied access to secondary services, pain medication, antibiotics and proper diagnostic investigations.

“People leave these places sick,” he said because of the racist attitudes of some medical professionals.

Lavallee points to what he calls the “classic” example of anti-Indigenous racism in the health care system with Brian Sinclair, who died in a Winnipeg hospital emergency waiting room in 2008 after being ignored by staff for 34 hours.

“That wasn't one episode of racism. We get calls all the time from the ones who actually have the energy to call us and make complaints to have their cases examined and advocated for. (It’s) all the time across Manitoba. This is not just the north. This is everywhere,” he said.

“However, isolation factors, poor attention by the provincial government, it’s propensity to only want to deliver services in southern Manitoba to predominantly white people is another way that racism rears its ugly head on the day-to-day living of First Nations people.”

Lavallee says the federal and provincial governments need to come to the table and be willing to both embrace and fund the innovative ideas that First Nations leaders put forward to address the health issues of their people.

“(We need to) go beyond the nursing station model. Look at new models of providing primary care. We want to do that as well as dealing with things, like harm reduction, (which) is absolutely necessarily needed right now. But the current system does not have enough support in general,” said Lavallee.

Instead of nurses only working at the stations, there needs to be “a whole slew of other providers that we can mix in a different kind of blend of primary care” including occupational therapists and respiratory care therapists.

“Those systems are old and antiquated. We've got to put our heads together to find something better to match each community and really that's where we want to go,” said Lavallee.

Moquin said the nursing stations do have an “inter-jurisdictional team,” which includes physicians, paramedics, dental therapists or hygienists, and community health workers. Statements provided to Windspeaker.com by both the federal and provincial governments committed both levels to working with the First Nations.

“It is important to our government that First Nations leadership and health professionals have a direct role in developing and implementing healthcare plans that prioritize First Nations people on and off-reserve, as well as northern and remote communities,” said a government spokesperson for Health Minister Audrey Gordon. “Manitoba is at its best when First Nations leadership and health professionals are at the table, helping make the best decisions for their people and communities.”

The spokesperson also said that Gordon was in the process of arranging a meeting with MKO and KIM “to continue the discussion of improving health and wellness services in Northern Manitoba and for advice on other ways to fight racism in our healthcare system.”

As for ISC, Moquin said, “The health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples and communities is a high priority for our government (and)… ISC continues to work directly with First Nations communities to ensure their health care needs are met.”

Lavallee says the goal of KIM is to transform health in Manitoba’s north and take control of health services.

“We don’t want the status quo anymore,” he said. “(We want) to rejig (services) in a different way…We need to work in community and work out of community, so we have better flow and access to resources, all those kinds of things. That's what we want. Patients just want to be treated better. They want to be treated with respect and that's really hard to find sometimes… with doctors and nurses.”

In 2018, MKO signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Health Transformation with Canada. MKO created KIM to meet that goal.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.