Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

The coronavirus pandemic has brought to the forefront the social and racial inequities faced by Indigenous peoples throughout Canada. First Nations communities, particularly, are a stark indication of those disparities.

In March 2020, when Canada declared a public health emergency because of COVID-19, many First Nations leaders took the bold step of closing their borders and actively patrolling access to their communities in an effort to keep the highly transmittable and deadly virus from their populations.

Those steps were necessary because of conditions on the reserve, including overcrowded houses which made isolation impossible, one way to stop the spread of the disease; lack of easy access to clean running water, with regular hand washing another way to control the virus’ spread; and because of pre-existing health conditions that plague many members, making them more susceptible to contracting the virus and less able to fight it.

According to statistics provided by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), as of Jan. 11 there have been 59,793 confirmed positive COVID-19 cases on reserves with 573 deaths. ISC says the confirmed positive cases are an under-estimation because of home testing and individuals choosing not to get tested.

Almost two years into the pandemic and with the fifth wave and Omicron, a most virulent strain, upon the country, conditions on First Nations have not changed.

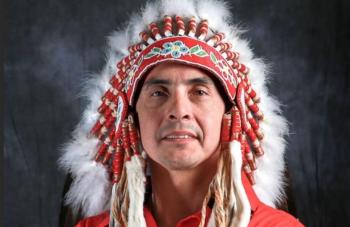

And that’s a point Arlen Dumas, grand chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, wants to drive home.

“Unfortunately, if I could wave the magic wand and COVID was to be gone tomorrow, well then the systems would gladly go back to the status quo and continue the systemic discrimination, the systemic racism and the chronic underfunding, and all these things will remain the same if we don’t take the opportunity to actually change what needs to be done. And we don’t have to wait,” said Dumas.

Late last week, when Niki Ashton, NDP Churchill-Keewatinook Aski MP, called for military help for the northern First Nations in Manitoba, it underscored Dumas’s concerns about the ongoing “colonial perspective that somebody else should be speaking on our behalf.”

He said Ashton had “disrespected” the process that Manitoba chiefs and nations had established nearly two years ago.

Among those processes is a First Nations Pandemic Response Coordination Team (PRCT), which brought together the “best and brightest” from First Nations organizations in Manitoba to lead an informed status-based response. They are supported by rapid response teams, funded by ISC, and the ambassadors program.

The military has provided help to Manitoba First Nations. From late 2020 to early 2021, soldiers were on the ground on a number of northern First Nations helping to manage COVID-19 outbreaks and rolling out vaccines. Military support was requested by impacted chiefs.

“I’m not saying we don’t want the help. I’m saying it has to go through the proper process. Our chiefs should be calling. Our health leaders should be calling. Not some out-of-touch tone-deaf MP who is essentially trying to… sensationalize the issue,” said Dumas.

“We’re well aware of our liabilities. We’re well aware of our vulnerabilities. We have taken very pro-active steps.”

Right now, the concerns are the Delta variant in the northern communities and the Omicron outbreak in the southern communities, said Dumas.

According to numbers provided by the PCRT, as of Jan. 6 there were 1,080 active cases of COVID-19 on reserve and 1,197 off-reserve. Total deaths to date are 111 on-reserve and 170 off-reserve. First Nations deaths in Manitoba represent 20 per cent of the total deaths in that province.

The impact of COVID-19 will continue as a concern until commitments are made and steps are taken by the federal government to address the historical issues facing First Nations people, said Dumas.

“We really need to focus on facilitating that long-term commitment and long-term investment to address these issues so our communities are not as vulnerable as they are,” said Dumas.

He says he wants commitments from the government on housing and infrastructure and he wants to see action now. He uses the government’s response to First Nations when COVID-19 first hit as an example of rapid deployment.

“At the beginning of the outbreak, because of the stance of the Manitoba chiefs and our vigilance and our informed fact-based proposals, we were able to get resources from Ottawa to our member First Nations in four days so that communities could protect themselves. Anything is possible. I don’t want to use the term ‘long term.’ They need to be called something else. We don’t have time,” said Dumas.

“There’s no reason to waste a great crisis,” said Dumas, and he’s not being glib.

“If I were to wave a magic wand tomorrow and I could make COVID vanish, I guarantee you the institutions, the division of authority, all these mechanisms that have been used to prevent First Nations from advancing, will gladly be reinvigorated.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.