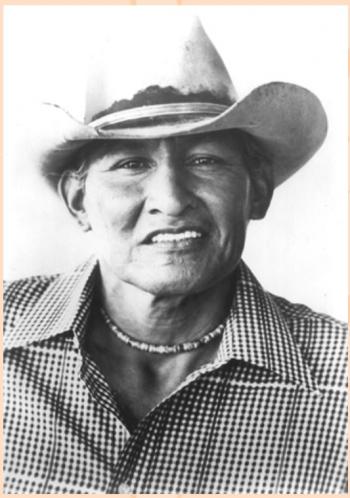

Image Caption

Summary

Windspeaker.com Archives

There was much more to Will Sampson, a Muscogee Creek man, than the 22 films he made between 1975 and 1986, said sister Norma Sampson Bible. For one thing, she reveals in a book call Beloved Brother, that Sampson, who died in 1987 at age 53, was recognized for his paintings and drawings long before he achieved notoriety as the first Native actor to break the mold of demeaning Native film actor stereotypes.

"First of all, before he was ever anything else, he was an artist. It was his first love," said Bible.

As a young man, Sampson, known as "Sonny" to his friends and family, had numerous commissions, sales and public exhibitions to his credit. His paintings and sketches of Western and traditional Native themes are distributed across the United States, in the Smithsonian Institute, the Denver Art Gallery, the Gilcrease Institute, the Philbrook Art Museum in Tulsa, Okla., the Creek Council House in Okmulgee, Okla. and in private collections.

"He was self-taught. From the time he could hold a pencil in his hand, that boy drew," his sister said. "When he didn't have no paper and pencil, he'd draw on the ground.

"Before he even went to school, me and my sister would bring our books home, and if he couldn't find any clean paper, he'd draw on the covers of our books. We'd get mad, and take his pencils away from him. I never dreamed that later on I wouldn't even be able to afford one of his paintings after I used to wad his papers up and throw them out."

Despite Bible's efforts to highlight all of her brother's accomplishments, it's likely it will be Sampson's unique contribution to the movie industry that most people remember, beginning with his portrayal of Chief Bromden in the 1975 production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest alongside Jack Nicholson.

Up to then, most Native American film parts were played by non-Native actors who couldn't speak Native languages and who didn't care about cultural authenticity.

Sampson's film debut as the silent, sharp, supposedly catatonic mental patient Chief Bromden is credited with changing the prevailing Hollywood images of Indians. Up to then, Native Americans were portrayed as illiterate sidekicks, self-effacing non-self-starters, and otherwise cast in servile or unsavory roles. Usually, Italians or Mexicans got the parts, as bad as the parts were.

Sampson rankled at the disrespectful way Native people were portrayed in film and he had a lot of anger towards white people generally, his sister said.

In her book, Bible talked about her brother's roles as activist, advocate and rolling stone.

She admits he drank, and that he had a hard time staying in one place long enough to be a family man, although he had nine children. He worked at a lot of jobs to support them, though, before he got into acting. He was a construction worker, oil field worker, linesman. Bible said that while "he was never involved in any everyday (tribal) activities he just always was proud of the fact that he was a Muskogee Creek. He was a full-blood, and he built them up just every chance he could."

During his sporadic visits home "he would go to the stomp dances, go to church with us and visit and then something else would come up and off he would go.

"Then in between there, of course, he had marriages.

"He was in the navy from 1953 to 1955, I believe it was ... and after he got out he was gone again ... doing whatever he could to earn a living. And all the time, he was painting, drawing.

"Some of his paintings sold and he'd have a high old time. And then use that up and he'd be looking for work again. You've heard of starving artists; I guess that's what he was."

Bible's book also strives to clear up false stories about Sampson perpetuated by various media over the years. His image stands tall enough on its own without any embellishment, she figures.

For instance, one newspaper reported Sampson was a navy pilot, Bible said, "which he wasn't. He was in the navy and somewhere along the line he learned how to pilot a plane, but he was not a navy pilot."

She said her brother became an actor by happy chance.

"What he told me, he was up there in Yakima, Washington, somewhere up there in the mountains painting and drawing and coming down once in a while. He said he had a friend in town. He came down to check his mail or something and his friend told him that they were in town casting for a movie and said they needed 'a tall, ugly Indian.' Those were his words... So my brother thought, 'Why not?' He was always one to take a gamble anyway.

"So he walked to this casting office ... they said the minute he walked in the door, they said, boy, they had found their Indian. So he was the mute Indian in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

Bible said her brother had a serious side. Sampson demonstrated against the oppression Native Americans experienced every day, not just in films.

"In between his movie roles, Sonny also found time to travel to other Indian reservations and towns to speak on their behalf about their problems. He told me he had begun to read up on tribal politics and government... His lifestyle was slowly beginning to change. He would still drink and he still had his wild moments, etc., but slowly and surely, he was letting up."

Bible went on to say that Sampson, who she believes completed school only to Grade 9 and who started out as a rodeo rider at age 14, struggled one time to decide whether he should accept a speaking invitation at an Indian school graduation in South Dakota.

He told her, "I get all mad again when I think about how the Indians have been mistreated all these years, and I can give them hell, but I never even finished school myself, so what can I tell these kids?"

"By the very fact that you didn't finish school and had a rough time of it, that should make them realize that they need all the schooling they can get," Bible advised him.

Sampson became a founding member of the American Indian Registry for the Performing Arts, which helped American Indian performers and technicians get work, and which pushed for cultural accuracy in scripts in the last decades of the 20th century.

Sampson also worked to promote accurate on-screen portrayals of Native Americans by joining the board of the American Indian Film Institute (AIFI).

That non-profit organization also wants Sampson's legacy preserved, which is the reason it is chronicling his "life, art, and love of adventure" in a documentary.

Michael Smith, founder and president of AIFI, stated in a publicity release that "Will's legacy is the path he cleared for non-stereotypical roles for Native peoples ... There remains much work ahead to clear the world of misconceptions and misrepresentations of Native Americans in film. Will's life challenged the status quo. We are proud to begin the process of making this documentary film."

Sampson's sister and his son Tim are creative consultants on the documentary. Others on the team are Smith, Phil Lucas, Alanis Obomsawin and Wishelle Banks.