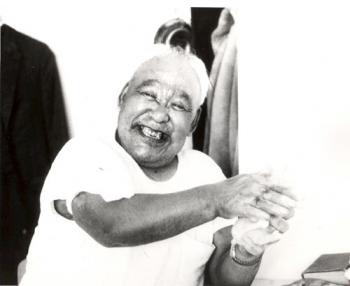

Image Caption

By Cheryl Petten

Windspeaker.com Archives

Joe Talirunili was born in northern Quebec near Kuujjuaraapik on the shores of the Hudson Bay. There are differing accounts as to the year of his birth. Government records show he was born in January 1899, but he claimed to have been born in 1906.

In either case, he was present to experience the traditional life lived by the Inuit in the area, and to witness firsthand the changes that would come as his people became more and more influenced by the outside world.

Talirunili grew up around the Great Whale River and the Richmond Gulf, joining his father in the hunt and living in the traditional Inuit way. But as time went on the Inuit had more and more dealings with the white men who came from the south. That interaction brought with it many changes to the way the Inuit lived their lives.

In some ways Talirunili embraced the changes. He gladly used the rifles introduced by the white men who came to the area to ensure greater success in the hunt. He found work as a guide for people from the south who came to the area to trap and also found work in the mining sector.

His was the first family in the community of Povungnituk to live in a pre-fabricated house. But he also stuck to the old ways, trapping, hunting and fishing to put food on the table.

Talirunili had a reputation of being a good, caring man who was always ready to share what he had with others. He could be counted on to provide visitors to his home with food and to entertain them with the stories he had to tell.

From his encounters with western culture, Talirunili learned the power of paper, of how it could be used to capture and share information. Seeing the possibilities this new medium offered as a way of recording stories about the old ways and passing them on to others, Talirunili became one of the first Inuit in the area to try his hand at printmaking, an art form that involved carving an image in stone and using it to print copies of the original piece of art.

While in some areas of the north where printmaking was introduced one artist would draw a picture and another would carve it into the stone, in Povungnituk, artists like Talirunili would usually create the image directly on the stone.

In the late 1950s, Talirunili and his cousin, fellow artist Davidialuk Amittu, helped found the Povungnituk print shop, where artists from the community worked to create prints reflecting the Inuit way of life. The print shop closed in 1989 but was resurrected, allowing a new generation of artists a chance to learn carving and printmaking.

In his work, Talirunili captured a way of life his people lived when he was young, before the influences of white society had changed it irrevocably. His efforts to capture these images of days gone by earned him the title of The Chronicler.

In his carvings, drawings and stone-cut prints, he created images of hunting scenes and figures of Inuit people, often adding descriptions to the drawings written in syllabics to explain what was going on in the scene depicted.

He also liked to draw and carve owls and his renderings of these creatures could be found in many of his creations. But Talirunili is probably best known for the great number of carvings through which he retold a tale from his childhood.

A very young Talirunili was among a group of family members and friends who were returning to their camp on the mainland after celebrating his baptism on an island in Hudson Bay when the ice over which their sleds were travelling began to break up and they became trapped on an ice floe.

Working quickly to complete the task before the ice under them melted and plunged them into the icy waters, the stranded travellers used the wood from the sleds and the sealskins on hand to fashion a boat that could get them to shore.

It's estimated that Talirunili created 25 to 30 carvings depicting this adventure. Each of these pieces has come to be known by the same name—Migration. The treacherous journey depicted in the Migration works was just one of many adventures and adversities Talirunili experienced during his lifetime and many of these other experiences found their way into his work as well.

During one voyage Talirunili took out his Peterhead boat with his son Joshua and seven others. The boat smashed into a reef and was destroyed. Talirunili salvaged what he could from the wreckage to fashion another craft.

The new boat, which relied on a 10-gallon keg, a large wash basin and a tea kettle to keep it afloat, proved sea-worthy and allowed Talirunili and his son to join other survivors of the accident who had managed to swim to a nearby island.

A family of four—a father, mother and two of their children—had also tried to swim to shore and had perished during the attempt. Talirunili chronicled that experience in his carving Near Death in Boat. The piece shows the boat, the 10-gallon keg in the back, and Talirunili and his son paddling, Joshua safely ensconced within the wash basin.

Talirunili died on Sept. 11, 1976. In the year proceeding his death, he produced an incredible number of carvings, including a number of new versions of Migration. His work has been featured in exhibitions across Canada and the United States and pieces of his art can be found in museums and art galleries across the country.

In 1978 one of his Migration sculptures was reproduced on a Canadian 14-cent postage stamp. Talirunili's art was in the news one of his many Migration carvings sold at an art auction for what is believed to be the highest price ever paid for an Inuit sculpture.

An unidentified Canadian bidder bought the sculpture for $278,500 during the auction at Waddington's auction house in Toronto. What set this Migration carving apart from the two dozen or more Talirunili created is that, while most of the carvings depict the passengers in the boat as human, for this carving he chose to populate the craft with animals—rabbits, an owl and a wolf.

In 1999 the auction house had sold another carving in the Migration series that featured animal passengers, this time owls and a dog. That carving sold for $50,600, a price that at that time was believed to the highest price paid at auction for an Inuit carving.

Two years later yet another Migration carving was sold at auction by Waddington's, again fetching a record-setting price, $87,500. Another version of Talirunili's Migration carving, part of the TD Bank Financial Group's collection of Inuit art, is featured in the exhibit ItuKiagatta!—a word from the Labrador Inuit that means "How it amazes us!"

The exhibit premiered at the National Gallery of Canada in April 2005 and has since travelled the country, showing in Winnipeg, Halifax and Edmonton.