Windspeaker.com ARCHIVES

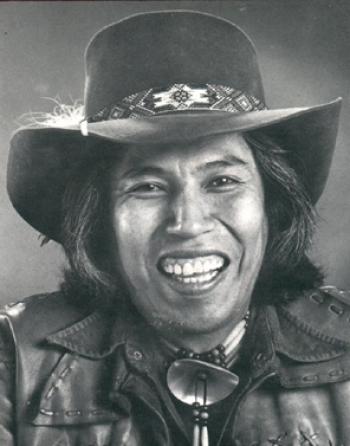

Jackson Beardy's life began on July 24, 1944 on Garden Hill First Nation, an Oji-Cree community on the shores of Island Lake in northeastern Manitoba. Forty years later, on Dec. 7, 1984, his short life came to an end.

In that time, the young artist used his talents to reconnect to his Native identity, and later to inspire and encourage other young Native men and women to express themselves through art.

The fifth child of 13, born to John Beardy and Dinah Monias, Jackson was given a special task at a very young age. He would live with his grandmother, his father's mother, and learn from her the traditional stories of the Cree people. His education in legend and tradition, however, was cut short when he turned seven and government policy of the time demanded he go away to residential school.

Beardy attended Portage Indian school in Portage la Prairie, 50 km west of Winnipeg and hundreds of kilometres away from home.

He spoke no English when he arrived at residential school, only Cree, and that was forbidden, as were many of the traditions that had, up to now, been a way of life for Beardy and his classmates.

Beardy learned to speak, read and write English, but the more he learned to meet the demands placed on him to adopt white ways, the more disconnected he became to his Native heritage and the things his grandmother had worked so hard to instill in him.

While his residential school experiences slowly chipped away at Beardy's connection to his culture, they also opened up doors for the young student that allowed him to hone his artistic talents.

Beardy attended the Technical Vocational school in Winnipeg from 1963 to 1964, where he studied commercial art. He finished the course, but without experience, couldn't find work.

He began to create art, reconnecting with the stories his grandmother had passed on to him in his childhood, combining them with the art techniques he had learned, capturing the resulting mix in paint on canvas.

He worked for a time in the display department of the Simpson Sears department store in Winnipeg, but lost the job when health problems began to plague him. Beardy had begun to drink after leaving residential school, one of the ways he tried to cope with the feelings of isolation that he felt.He soon developed ulcers.

Problems related to his drinking would plague him for another decade, until he gave up alcohol in 1974. The ulcers would continue to be a problem for the remainder of his life.

Beardy was hospitalized for the ulcers and after his release, he decided to return home to Garden Hill reserve. His homecoming wasn't all he had hoped it would be. He was seen more as an outsider than as a member of the community returned, a view that was strengthened by the art he produced.

The images Beardy created in his work were taken from oral tradition, and many people were not receptive about capturing them in a visual form.

Beardy had his first art exhibit in 1965 at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. In 1966 he took some art classes at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Manitoba. In 1967 he went to Montreal as a consultant for the Canadian Indian Pavilion at Expo '67. He received commissions to produce works of art to commemorate both Canada's centennial in 1967 and Manitoba's centennial in 1970.

It was in 1970 when one event presented Beardy with both a great accomplishment and a bitter disappointment. It illustrated the struggle Native artists faced in their attempts to be recognized and respected.

A grand gala was held at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa to commemorate Manitoba's centennial, and Beardy's work was to be featured. Beardy was invited to attend the gala, but when he arrived with his family, security guards wouldn't let him in.

One of the highlights of Beardy's artistic career was his involvement in the exhibition Treaty Numbers 23, 287 and 1171, in which his work was featured alongside that of Daphne Odjig and Alex Janvier.

The exhibit, held at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1972, marked a movement toward having the work of Native artists showcased in art galleries rather than museums, a sign that their art was finally making the jump from being appreciated for its anthropological merit to being viewed as true art. That same year, Beardy was awarded the Canadian Centennial Medal.

Beardy was one member of a group of Native artists who formed the Professional Native Indian Artists Association, better known as the "Indian Group of Seven." Beardy, along with fellow group members Odjig, Janvier, Norval Morrisseau, Carl Ray, Joseph Sanchez and Eddy Cobiness, worked to promote Native control of Native art.

They endeavored to change the way the world looked at Native art, shifting the emphasis from the "Nativeness" of the art to its artistic merits.

Like other members of the group, Beardy's work is categorized as being part of the New Woodland school, a style of art characterized by its use of black outlining, blocks of pure, undiluted color and X-ray views.

Beardy drew inspiration from much of his artwork from the stories of his people, translating myths and legends from the oral tradition into the visual, presenting his interpretation of the stories through paintings and prints, rendering the images on canvas, birchbark or beaver skins.

While capturing the essence of the stories he had learned as a young child and relearned as an adult, Beardy's work reflected traditional Native viewpoints about the interconnectedness of the universe.

While primarily an artist, Beardy spent much of his time in the role of teacher, something that came naturally to him because at the heart of it all he was a storyteller. He taught art at Brandon University and at the University of Manitoba, and also worked with younger students in schools across Winnipeg.

He worked as art advisor and cultural consultant to the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature and Brandon University's Department of Native Studies, and was involved in a number of organizations that advocated on behalf of artists.

Beardy also turned his talents to the world of publishing, illustrating a number of books, including “When the Morning Stars Sang Together” written by John Morgan, “Almighty Voice” by Leonard Peterson, “Ojibway Heritage by Basil Johnston and the Winter 1983 issue of “The Canadian Journal of Native Studies”.

In the early 1980s, Beardy was living in Ottawa, acting as art advisor and cultural consultant to the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, which took up much of the time he would have normally been spending on his art.

In 1984, he left Ottawa and returned home to Winnipeg, where he began work on a new series of prints. In mid-November, Beardy suffered a heart attack. He recovered, but an infection set in a few weeks later and he died.

A memorial service was held for Beardy in the Blue Room of the Manitoba legislature where the lieutenant governor holds ceremonies and hosts receptions, the first time such a service had ever been held in that location.

Joining Beardy's family in mourning their loss were Elders, Native leaders, and politicians from all three levels of government who came to remember and pay tribute to the artist and the man.

The year after Beardy's death, the graphics arts class at R.B. Russell Vocational high school in Winnipeg created a lasting monument to his work, recreating Peace and Harmony, a piece he had been working on just before his death, on the exterior walls of the Indian Family Centre on Selkirk Avenue.

Jackson had planned to create the mural himself, but following his death the task of finishing the project fell to other hands.