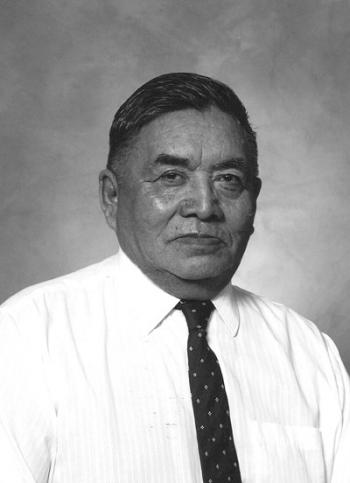

Image Caption

By Dianne Meili

Windspeaker.com Archives

Dene author George Blondin was one of the few Aboriginal people who spoke openly about medicine power, because he felt young people should know where they came from.

The prolific writer passed away at the age of 87 on Oct. 12, 2008 after suffering a stroke this year in his Northwest Territories home. Blondin was candid about the past, going so far as to reveal his own medicine power story in his first book “When the World was New”.

At five years old he was sent to get water early in the morning when an “old man with long white hair” rose from the lake and startled him. Dropping his pail, he raced back to the family tent and his mother’s lap.

Since he had not naturally embraced the spirit, his parents resigned themselves to the fact he wouldn’t be a medicine man and stopped trying to help him get power. Blondin writes that he should have welcomed the power-bringer, but instead, resigned himself to working hard in a mundane life like most people.

“My father wasn’t trying to be disrespectful when he spoke of these things,” said Blondin’s son, Ted, who explained his father grew up in times extremely different from today.

Even in 1923, when George was born in the Great Bear Lake region of the Northwest Territories, people relied on medicine power, not money. Having medicine power meant having a successful life, perhaps being a good hunter or healer, or knowing about events before they happened.

“My father wrote about these things because they are important to being Dene,” said Ted, and he wanted young people to realize this part of themselves.

“Medicine power is a phenomenon that is hard to understand and so it is not spoken of openly. But my father meant only to preserve this knowledge and he worked hard to explain it. He knew young people weren’t sitting around the fire listening and talking to the old people so much anymore, and so he wrote down stories so they could read them.”

Blondin preserved countless stories of life before contact in minute detail, indicating how precise his memory was right up until his passing.

“A lot of his stories describe how people could interact with animals, and how the spirit of a man could change into a caribou, for example. This man would then learn of caribou nature – how they reacted to certain things, how they moved on the land and where they liked to stay. Then, back in his human spirit, he would have a good idea of where to hunt for them,” Ted explained.

Due to mutual compliance, good hunters never failed to perform certain rituals for animals when they died so they could be reborn, thanking them for sacrificing their lives so humans could live.

Interpretation of the way the world works has been lost, Blondin believed, and so he published three books conveying stories with spiritual themes. The public is receptive to them, and his last title, “Trail of the Spirit; Mysteries of Dene Medicine Power Revealed”, published in the fall of 2006, was a NeWest Press bestseller.

“I found more of my father’s papers in a briefcase when I cleaned out his apartment,” said Ted, explaining his father was an incessant writer who had a fourth book in the works and enough material for a fifth. Many of his stories were also printed in a long-running weekly column in Yellowknife’s News/North.

“My father might be washing the dishes and thinking about something when he’d get the urge to write it down,” said Ted. “One time he left the water running and sat at the table scribbling away. When the water wet his feet, he just lifted them up and kept writing, that’s how focused he was.

“And he had a story for everything. At a bookfest in Whitehorse, he was interacting with his audience when someone asked him what earthly good were mosquitoes. Not missing a beat, he was able to launch into a story about a hunter sitting on top of a hill near a lake on a very warm day, looking to hunt a moose to bring meat to his family. Pretty soon, the swarms of mosquitoes drove the poor moose into the lake’s water and the hunter made his kill there. He was able to illustrate to the crowd how the mosquito is a hunter’s best friend.”

For his storytelling efforts, Blondin received the Ross Charles award in 1990 for Native journalism and was inducted as a member of the Order of Canada in 2003.

Keenly interested in the future as well as the past, Blondin attended political meetings dealing with issues from land protection to jobs in the Northwest Territories.

“He was set to attend an economic conference just before he died,” explained Ted. “He really cared about his people and he made sure all of his children were educated so we could go on to help people.”

But Blondin’s first love was the land, and he abandoned hunting and trapping only when he lost his first son to pneumonia in 1958. After that, he moved to Yellowknife to be closer to the hospital and schools for his other children.

He holds no malice over the fact he was given underground jobs at Giant Mine that no one else wanted to do, because he was Aboriginal, he surmised, and simply moved back to Deline (Fort Franklin) to resume hunting and trapping as soon as his children finished school.

It didn’t take long for him to be elected chief of the Deline First Nation in 1984, and to serve as Dene Nation vice president later.

At the time of his death Blondin was living independently in Behchoko (Rae-Edzo) just outside of Yellowknife, though residential management didn’t want him cooking for himself.