Image Caption

Summary

Originally published in November 2011

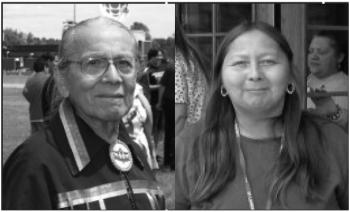

This year’s passing of Elder Ernest “Ernie” Kaientaronkwen Benedict and his daughter Salli Kawennotakie Benedict deprived the Mohawk community of two great visionaries. Both dedicated their lives to strengthening their nation’s identity.

The elder Benedict was born in 1918 at a time when his people were still tied to their natural environment, nourished by the crops they grew and the fish they harvested from the many rivers flowing through Mohawk Territory.

Ernie matured while the Canadian government imposed its administrative authority over the northern part of Akwesasne, and New York State created a colonial government to wield control over the south. Ernie observed how both undermined ancestral ways and served to splinter Mohawks into hostile factions.

Partnering with Ray Fadden-Tehanetorens, Ernie sought to remind people of their heritage at a time when it was considered regressive by mainstream society. Akwesasne members, as well, felt cultural activities and values would hinder their advancement.

To battle oppression, the two men rallied Mohawk youth to form the Akwesasne Mohawk Counsellor Organization. Over many years the group “travelled throughout the eastern part of North America, visiting historic sites, meeting with other Native nations, learning about their own heritage while coming to the conclusion that Indigenous peoples had meaning and substance beyond the qualifications set upon them by Europeans,” wrote former Akwesasne Notes editor Doug George-Kanentiio in the online resource indianz.com.

The travels by two men would lead them to develop the unity caravans of the early 1960s and then to the formation of the White Roots of Peace, which lit the flames of Aboriginal nationalism across the continent, changing the way mainstream society viewed “Indians.”

Ernie went on to edit two newspapers reporting the actions of Akwesasne leaders all the while endorsing a unified Mohawk front. Later, he would co-found the influential journal Akwesasne Notes. He earned a university degree when few of his peers made it past high school, wrote George-Kanentiio, and famously opposed the draft during the Second World War utilizing his vast knowledge of Iroquois treaties “when almost everyone else simply conceded to it.

“He also saw the dangers of sending our students off to distant schools to become a darker shade of the European education system. He knew the perils of their schools and how they were used to eclipse Mohawk history while demanding serious psychological and cultural compromises on the part of the Native student.”

Ernie’s Manitou College, still educating students northwest of Montreal, features Aboriginal faculty and students, and manifests his then-radical idea that the world must learn from Indigenous people, not the opposite.

Ernie may be best remembered for his North American Indian Travelling College which carried on from the White Roots of Peace. More than anything he wanted to influence others not to accept the status quo, but to realize the wisdom of traditional values and empower themselves with it to protect their lands and rights.

For years he drove across the northeastern part of this continent with his library of books and personal knowledge, sharing both with an attentive younger generation ready to take action against the government.

Ernie passed away in January of this year at the age of 92, and Salli, his daughter who was said to be so much like him, followed in May at the age of 57. Both took great pains to preserve Mohawk heritage and win gains for their people in many areas.

“They were as humble and generous as they were wise,” said friend and colleague , who works for the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (MCA). “Salli was always so full of life and passion. She had such stamina in the face of the disabling effects of rheumatoid arthritis.”

Could the eldest Benedict child have been anything less than a champion of Aboriginal culture, values and rights, given her parentage? In addition to her father’s influence, her cultural avocation was enhanced by an artistic bent gained from her mother, Florence, whose baskets are exhibited in Canadian and American museums.

At the age of 20, Salli served as interim director for her father’s travelling college and then went to Salmon River Central School, teaching children in the Title 4 Cultural Program where she made storyboards illustrating Aboriginal cultures. She went on to work for the Akwesasne Museum for many yearKarla Ransoms, formally establishing curating policies and procedures to protect historical documents and artifacts.

Her love of history, archaeology and anthropology led her to the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe where she acted as a cultural historian involved in land claims and researching.

“More than any other person, Salli deserves full credit for the creation of the Akwesasne Communications Society which in turn established Radio CKON,” wrote George-Kanentiio. “She was tenacious but diplomatic using her skills to secure an agreement with all three Mohawk councils to have CKON the only exclusively Native licensed radio station in North America.”

“She was never heavy-handed. She was just devoted to the truth. If she didn’t receive a certain response, she just went to work and did more research to prove her point,” Ransom said.

An artist and author, Salli illustrated and edited children’s books, and was a published poet. She is cited and acknowledged in books, articles and documents referring to Aboriginal culture. She also wrote several Mohawk-language textbooks, according to the Standard Freeholder in Cornwall.

She was also a photographer, potter, sculptress and co-creator of many of the institutions found on Akwesasne. Her most recent position was with the MCA, where she was heading the Aboriginal Rights and Research Office.

MCA Grand Chief Mike Kanentakeron said in a statement it was especially painful that she would not be present to see to fruition the result of her efforts to settle land claims with the Canadian government.

“It is a testament to her hard work and commitment that our community’s land claims are being negotiated,” Mitchell said. “We wanted so much for her to be with us on the final leg of this journey. She was so much a part of negotiations, and she will still be with us in spirit. We will continue to work just as hard as if she was still by our side encouraging us all on.”