Image Caption

By Heather Andrews Miller

Windspeaker.com

Celebrating and strengthening Aboriginal culture was an important part of the life of Bob Boyer. The Saskatchewan-born painter used his art to showcase Indigenous cultural life, as well as comment on the treatment Aboriginal people have been subjected to since contact.

Born near Prince Albert in 1948, Boyer graduated from the University of Saskatchewan’s Regina campus (now the University of Regina) in 1971 with a bachelor of education degree specializing in art education.

Always proud of his Métis heritage, Boyer’s earlier work featured the traditional designs of the Northern Cree people. He was inspired early in his artistic career by the works of Ted Godwin, the award-winning artist and teacher known for a rich palette of styles and colors and whose Prairie heritage is expressed in his paintings.

Boyer also admired Norval Morrisseau.

Initially, Boyer worked in acrylics on canvas, but a trip he took to China and Japan, where he saw works of art created on cloth rather than canvas, inspired him to explore alternative mediums for his paintings.

This new broadening of his artistic horizons was coupled with a growing desire to bring about an awareness of Aboriginal art and history, and to address issues impacting Indigenous peoples.

It was during this period that he began to create the artistic work he would become best known for a series of paintings on blankets that he called his blanket statements. Through these paintings, Boyer sought to inform observers about the way Aboriginal people had been treated throughout the years.

The use of the blanket itself was an important part of that message, referencing the fact that, during the early years of colonization, Europeans distributed blankets infected with smallpox, which contaminated and killed thousands of Aboriginal people.

Boyer had the courage to highlight this infamous chapter in Canadian history and most critics appreciated the political statements.

Boyer created one of his most famous blanket statements—entitled A Minor Sport in Canada—in 1988. At the time, Boyer said he was inspired to create the piece after having a conversation with someone who said First Nations children have to be twice as good in hockey to make the team, a reality that repeated itself in other sports, in school, and indeed in all areas of life.

At about the same time, he read an article that said the troops at the Battle of Batoche looked at the opportunity to fight Indians and Métis as a form of sport. Combining the historical facts with contemporary themes, he created a powerful statement in the work, which features the image of a Union Jack merging into a background of traditional Plains Cree design, combined with splotches of red paint representing the blood spilled at Batoche.

But not all of Boyer’s works were so political and controversial in nature. Some of his pieces commemorated the sacrifices made by Aboriginal soldiers in times of war. One installation paid homage to Nathan Crazy Bull, who was one of the first Aboriginal people to die during the Vietnam War. Another told the story of a friend mistakenly declared dead after he had been shelled during the Korean War, but who arrived home alive and well to a surprised family.

In the mid 1990s, Boyer’s work took a sharp turn away from the strong political statements of his blanket works, and he instead turned his focus to friends, family, and celebration of culture.

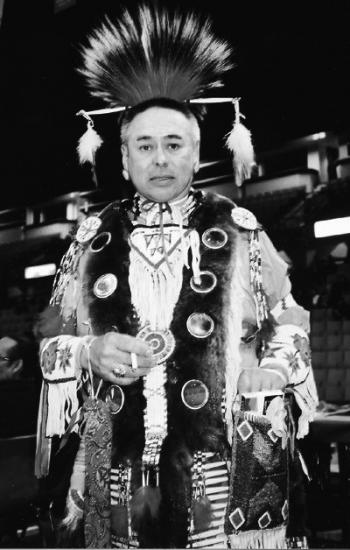

Boyer chose to celebrate his culture not just through his art, but through his actions as well. He developed a love of the powwow and participated in dances all over North America. He saw it as a celebration of a strong, vital Aboriginal culture on both sides of the border.

It was while he was on the powwow trail, attending a powwow in Nebraska, that Boyer suffered a sudden and fatal heart attack. He died on Aug. 31, 2004 at the age of 56.

While Boyer will be remembered as a courageous and talented artist, many feel his true legacy was in the young artists he inspired before his passing.

Before beginning his long association with the Mackenzie Art Gallery in Regina as community program director, Boyer taught art and drama in Prince Albert. By the 1980s, he was running a successful series of much-appreciated programs at the gallery, which included erecting a full-sized tipi, demonstrating powwow dances in full regalia, inviting Elders to meet with school groups, and teaching art programs for teens during the summer months.

He could often be found addressing a group of attentive youth, sharing the story of his life, and urging them to make the most of theirs. He served on the board of trustees for many years and was guest curator for many exhibitions over his 30 years with the gallery.

He also had a long-standing relationship with the First Nations University of Canada, where he was a professor and department head in the fine arts department for many years, and where he worked to pass on his belief that Aboriginal art should be viewed on par with all other types of art forms and to educate future generations of Aboriginal artists.

Bob Boyer, the man, will be remembered as quiet and kind; as a man who was passionate and had a great sense of humour and who liked to ride his motorcycle on Saskatchewan’s wide-open highways and spend quiet time with his wife, Ann, in their home in Rouleau, just south of Regina.

Bob Boyer, the artist, will be remembered as a man of incredible talent who made bold political statements, and for his artistic celebrations of Aboriginal history, culture and spirit.

And Bob Boyer, the teacher, will be remembered for his dedication to molding young artistic minds and inspiring them to follow in his footsteps.