By Heather Andrews Miller

Windspeaker.com ARCHIVES

The passing of Ben Michel in the summer 2006 at the age of 53 from a massive and unexpected heart attack has left a void in the leadership of the Innu Nation. For approximately 30 years, Michel advocated for Innu rights so his people could have control over their lives and their land. He devoted his entire working life to being a political leader and while still in his teen years and early twenties was actively participating in protecting the land and the way of life of his people.

Since those early years, Michel had passionately joined other leaders of the 2,000-member Innu Nation to achieve partnerships with the government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the federal government. Even before his election as president of the Innu Nation in 2004 he had been at the table of many comprehensive land rights negotiations and participated in numerous protests and evictions of mining companies who had begun development on Innu lands without permission or negotiation.

Ben—Penote in Innu — Michel was born on June 28, 1953 to Shimun Michel and Mani-An Michel of Sheshatshiu, Labrador, the fourth child of the 12 who would eventually be born to the couple. The English schools he attended at Sheshatshiu and Wabush gave him bilingual abilities, a skill he would find helpful later in his life when dealing with industry and government officials, but he always remained fluent in his Native Innu tongue.

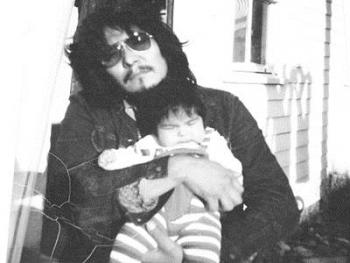

Michel and his siblings were taught by their parents to honor the land, and the family often enjoyed a traditional lifestyle. Later, he would pass on the same values to his own four children as he travelled the country to conduct negotiations and hold meetings about pertinent issues that would affect their future. He chose to drive to the many meetings he attended so he could bring his children along with him rather than leaving them behind at home. The family travelled every year to an annual gathering in Quebec, meeting with the Montagnais people with whom the Innu share their language and culture, but holidaying and relaxing as a family as well.

Michel was one of the people who could remember the Innu as a sovereign people with their own sustainable economy based on hunting, fishing and gathering. He saw the damage that mining, forestry, and hydroelectric projects were doing to the land and sought to ensure the Innu had a say in how these developments would unfold so that the environment could be protected.

One of the Innu’s first experiences with industrial development was the Churchill Falls power project in the early 1970s that proceeded to drown forever a portion of their hunting grounds, trap lines and ancestral burial sites without any consultation or negotiation with the Innu.

The unfortunate experience taught a young Michel and the Innu leaders that they needed to insist on meeting with government and industry to ensure they were part of the planning for any further developments. This set the stage for most of Michel’s career as he spent the rest of his life delivering this message and ensuring agreements were carried out. Members of the community united in showing great support in any action necessary to get the attention of those in control of non-Aboriginal development.

Michel was involved in protests concerning military low level flight training over Labrador and eastern Quebec in the 1990s. Canada and its NATO allies allowed supersonic jets to fly over the area, as many as 30 to 40 times a day, flying low to avoid radar detection and greatly disturbing the wildlife, causing caribou to miscarry and threatening the food that the Innu and other Aboriginal people in the area hunted for survival. Children were startled by the planes that appeared with no warning of their approach and, clipping the tree tops, flew over the home lands with a noise twice as loud as thunder. The protests went on for years.

When the extension of a logging road right next to the community was planned, again without consultation, Michel and other leaders gave an eviction notice to officials and workers and set up tents to ensure that once they left they did not return.

The protestors continued their presence until a series of meetings resulted in then-premier Clyde Wells agreeing to prevent the road from being extended. In 1994, the Voisey’s Bay nickel deposit was discovered in the area and the Innu found they were once again protesting the apparent ignoring of their rights as exploration of the area began without consultation.

Michel helped to organize and attend the protests, which were eventually effective and gave the development companies and governments notice that the Innu must be included in any further development. They were joined in this protest by nearby Inuit people, whose lands were also threatened by the mining development.

One of the many people Michel met during his years of political leadership was Dr. David Suzuki, and family members say that the two found they had many environmental concerns in common and a great mutual respect for one another and the work each was doing.

Michel wanted to share the spotlight as leader with those around him and he taught and trained others with his knowledge and skills, including Daniel Ashini, the new leader of the Innu Nation.

The incoming president has said he will continue working towards the vision he shared with his cousin, who was attending mining rights negotiations in Quebec at the time of his death in August. Ashini is a strong negotiator in his own right and has represented the Innu Nation in past land claims and numerous other activities, but admits the work is ongoing.

At the funeral held in Michel’s home community of Sheshatshiu, more than 500 overflowed a school gymnasium for a five-hour service of remembrance. In attendance were politicians, friends and family members. Condolences poured in from across the country and the Combined Councils of Labrador asked all communities across the province to fly their flags at half mast.

In a statement of condolence issued by the office of the federal minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Jim Prentice called Michel a man of the people, someone who spoke passionately about the right to self-determination and possessed both vision and the ability to carry out the work necessary to see that vision become reality.

Family members say near the end, Michel seemed always to be tired, as if his many years of political and leadership duties were beginning to take their toll.

He leaves behind his wife Janet, his four children— James, Yvette, Annette, and Megan—grandchildren, his siblings, nieces and nephews, and his parents. He also leaves an entire community that continues to mourn his too-early passing but which will be forever grateful for the difference he made in their lives through his efforts to preserve the culture and the way of life for so many people. He will be remembered as the father of the Innu people.