By Odette Auger, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter, Windspeaker.com

The Anishinaabe Academic Resource Centre and the Canadian Association of Science Centres hosted a webinar on star knowledge June 12 to bridge the perspectives of the ancient astronomers of Turtle Island with those of today’s astronomy experts.

The emphasis was put on the importance of embracing diverse ways of knowing and the creation of inclusive learning environments.

The webinar was hosted by Indigenous scientists Dr. Melanie Goodchild (Couchiching and Ketegaunseebee/Garden River First Nations) and Natasha Donahue (Cree, Métis) to bring together Indigenous wisdom and western education in a respectful way.

Donahue is on the steering committee of The Galileo Project at Harvard University, which searches the cosmos for evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence or technology. One of the Galileo Project’s goals is to “search for potential astro-archaeological artifacts or remnants of Extraterrestrial Technological Civilizations (ETCs) or potentially active equipment near Earth,” reads an article published in World Scientific https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/10.1142/S2251171723400032

Part of the methodology involves exploring “signatures of Extraterrestrial Technological Civilizations” from legends, and bringing those to “the mainstream of transparent, validated and systematic scientific research,” reads the Galileo Project’s website.

Of UFOs or Unidentified Aerial Objects (UAO) there are “thousands and thousands of years of reports,” Donahue said.

“I really, really deeply believe in collective effort and co-creation, understanding, creating and understanding together as a whole,” she explained.

Goodchild is the founder of the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab and the academic director at Makwa Waakaa'igan at Algoma University. Her PhD is on systems thinking and complexity science.

Goodchild is interested in “different worldviews coming together. Some of what we study in western education, which can be brought together with Indigenous wisdom,” she said.

“Historically, that's been kind of a clash and a domination of one way of knowing over the other.”

She said she’s interested in “taking the best of what we have from both worlds, but also being respectful of those distinct ways of knowing.”

Indigenous star knowledge stories capture teachings about land, medicines and animals, and our relations, Goodchild explained.

The fact we’re taught constellations by their Greek names, referencing Greek stories, “and we’re taught that’s universal”, is an example of assimilation, Goodchild said.

“That's the assimilation. That's ‘systemic violence,’ I've heard it called,” she said. “That's part of that genocidal project. Settler colonialism is ‘we're going to replace your way of thinking, your language and the way that your ancestors looked at something with this version.’

“‘And we're going to say it's universal, so you don't even question it. You just get taught it in Grade 4, Grade 12, and then you go to university. You get a whole degree in something that's from a worldview that isn't yours,” Goodchild said.

Goodchild doesn’t suggest we should dismiss one perspective over another. Rather she reminds her audiences of what the words “decolonizing” and “Indigenizing” mean.

“I need to understand that my way is valid, and it doesn't have to be verified or approved or recognized even by western ways of knowing,” said Goodchild.

Donahue acknowledged such limitations of the current colonial education system and stresses the value of experiential and holistic learning. She shares her experiences with Indigenous storytelling, “recognizing the relationality of different beings and ways of interacting.”

Both scientists highlighted the significance of storytelling and personal experiences in teaching and learning, and “the need to create generative social fields that foster collective wisdom and authentic engagement.”

Leading by example, the webinar respected protocols when sharing Indigenous knowledge. For example, Donahue explained that certain types of stories have their appropriate season to be told. She gives the example of Wesakechak, the Cree trickster, whose constellation is known by the Greeks as Orion, the hunter.

“I wouldn't tell Wesakechak stories or trickster stories in the summertime or when Wesakechak, the constellation, is no longer in the sky at nighttime,” said Donahue.

“This is a reciprocal relationship. Our oral tradition we place in the sky helps us to understand the land. But it also helps us to remember the oral history at the same time. So, we're engaging within something in a very holistic, web-like way,” said Donahue.

Indigenous peoples are the original systems and complexity thinkers, said Goodchild.

“We understand interconnected webs of life. Our whole language system is based on that and the teachings that we have of the stars really encode that way of thinking as well.”

It’s important to understand how we’re given “false teachings around the simplicity. That these are just stories and legends,” said Goodchild.

“There's deep intellectual and scientific wisdom and knowledge within that as well. But the colonial system degraded that and labeled it as inferior.”

“It's different to think of the sun and the moon as a relative, a grandmother and a grandfather, than it is to say this is the definition of the sun and the definition of the moon, making space for that,” Goodchild said.

Current curriculum often presents Indigenous knowledge in ways that are “paternalistic and condescending,” Goodchild said.

“There's a little box. Here's a quote from one Elder. And that's the curriculum, which is so far from any threshold of successfully bringing in our ways of knowing,” she explained.

Meaningfully making room in academia for Indigenous knowledge means recognizing the full scope of wisdom to be included, Donahue said.

“There's much more to these stories than just this orientation or this tangible information or knowledge. There’s information, knowledge in these stories about relationality, about culture, about how the universe works, about the exchange of energy, the flux of everything around us, the cycles of nature.”

“It goes so incredibly deep. And that web is so spread out, you could explore these oral histories for your whole lifetime. And, in fact, that's what people do,” Donahue said.

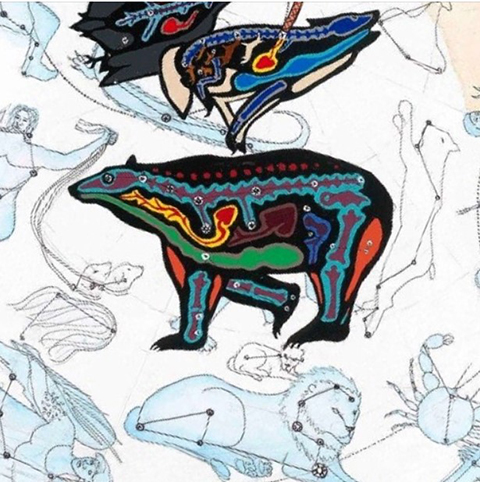

She uses the example of a story learned from Cree Elder Wilfred Buck about Mista Muskwa (The Big Dipper), the Great Bear and the Seven Birds.

You can hear Buck tell the Mista Muskwa story here: https://soundcloud.com/scifri/wilfred-buck-tells-the-story-of-mista-muskwa

“The handle of the Big Dipper is where the head of this Great Bear is, and the bucket is its legs. And this story is also told in the fall time during the eleventh moon, and it tells about why the leaves turned red in the Fall.”

“And it talks about standing up, right? Using your voice, using your power in the face of adversity even when you don't think you could win,” said Donahue.

The webinar demonstrated the use of Stellarium, an open-source software developed into a desktop planetarium, simulating the sky as if through a telescope that users can set to specific times and locations to explore the sky. And the talk highlighted specific constellations and their cultural significance, using technology to illustrate the wisdom in teaching stories.

Looking at the constellation Ursa Major through Stellarium, the webinar illustrated the Mohawk story of the Celestial Bear, facing the opposite way of the Mista Muskwa story. The four stars that make up the cup of the “Big Dipper” represent the bear itself. Three stars behind it represent the hunters in this story.

After sunset, the Celestial Bear runs along the ground chased by the hunters behind it. The bear first runs up a mountain and escapes into the sky, along with the hunters chasing it.

When one of the hunters comes forward and kills the bear, the blood and the fat from the bear fall to the ground, which is why leaves turn red in the Fall. The story can only be seen in the sky at the right time of year, which indicates the start of a hunting season.

In this way, storytelling and oral traditions are essential to understanding the sky and its teachings, Donahue said.

Goodchild gives an example of how Indigenous teachings are decolonized, and recommended Wendy Makoons Geniusz’ book, “Our Knowledge Is Not Primitive.”

She explained how scientists would go out on the land with Indigenous Knowledge Keepers. They would learn from them about plants and plant medicines and their properties. Then the scientists went “back to Europe, put those into Latin taxonomies and created textbooks and then (they) teach our five-year-olds the Latin word for something which they learned from us originally.”

This removed the knowledge from its original context. “To strip it of its spiritual teachings” and “then teach it to our children.”

Learning the teachings of the stars means to learn “stories which encode our value systems. It encodes the creation stories of different things.”

Goodchild explained that looking up at the sky is a beautiful tool “for teaching and learning. It's so powerful when that can be personally experienced.”

This webinar is the first of what will become a series. Facilitators recommended also learning from Native Skywatchers, the Anishinaabe Sky Star Map, and resources from Elder Wilfred Buck.

Top photo: At right is a photo of Natasha Donahue. At left is a photo that appears with the Soundcloud story of Mista Muskwa by Cree Elder Wilfred Buck.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.