By Odette Auger, Windspeaker Buffalo Spirit Reporter

Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson (Haida, Raven clan) is a musician, activist, artist, lawyer, and author. Her latest book is created with her husband, renowned Haida artist Robert Davidson (Eagle clan).

Together in A Haida Wedding from Heritage House, they document the seven steps of guud ‘iina Gihl (becoming married) in Haida law.

The book, conceived as a visual narrative, is an ode to the visual and oral richness of Haida culture. Sharing the preparation and process, A Haida Wedding showcases the respect and reverence for tradition that underscores every decision made.

It’s also a love story that grew out of their dedication to the perpetuation of Haida culture.

The art of cultural continuity

Terri-Lynn’s maternal great grandmother was a song custodian, and Terri-Lynn carries the talent for singing. By age 13 she had started a children’s singing group. She was given the name LalaxaaygansIt, meaning beautiful sound coming from within the house or behind the screens within a longhouse, she said.

It was through singing that she met Robert, whose Haida name is ![]() Eagle of the Dawn. Robert and his brother Reg Davidson had begun the tuul gundlas cyaal xaada, Rainbow Creek Dancers in 1980.

Eagle of the Dawn. Robert and his brother Reg Davidson had begun the tuul gundlas cyaal xaada, Rainbow Creek Dancers in 1980.

Growing up among the remnants of the stolen totem poles of Masset in Haida Gwaii, Robert developed his skills to become a master of Haida formline. Learning came from his father, grandfather, “and the old masters.” His great-grandfather was famed Haida carver Charles Edenshaw.

On Aug. 22, 1969, Robert was the 22-year-old carver of Mother Bear, the first totem pole raised in Masset in nearly a century. His motivation was “to allow my grandparents' generation to celebrate one more time in a way they knew how, because we were just starting to move out of the potlatch ban," Robert explained. “And many people of that generation were still afraid that we would be punished both by the Church and the Indian Act.”

Potlatches are gatherings that allow for such things as the giving of traditional names, the transfer of wealth or titles and responsibilities, the commemoration of the life of a high-ranking individual after death, or the celebration of weddings, births and other milestones.

The Indian Act of 1876 allowed for the abolishment of all First Nation cultural practice. The Potlatch ban came into effect under the Indian Act in 1880. It had the effect of sending West Coast ceremonies underground, but mostly it stopped them from occurring altogether.

Masks and other ceremonial items were taken from their owners, destroyed or absorbed into museums and private or church collections of art and artifacts. Carved poles were cut down and shipped away. Anything that kept First Nations connected to Indigenous tradition, culture and spirituality and which slowed their assimilation into Christian white society was dismantled.

Traditionally, a pole in Masset would have been raised by one of the two clans in the village—Eagle or Raven. To celebrate the occasion of raising the Mother Bear pole, Robert felt the members of both clans should join in. It was a combination of innovation and tradition and was a catalyst of cultural revival.

Exactly 27 years later on Aug. 22, 1996, Robert and Terri-Lynn marked their union as individuals, families, and clans. Traditionally, only the clans of the bride and groom were invited to weddings. In the spirit of inclusion and innovation, the couple invited guests from interconnected communities and beyond.

“Ceremonies must be relevant to who we are today,” said Terri-Lynn. “We arrived at something that was relevant for us today and something that would yet honor our ancestors who were able to keep that knowledge alive, despite not being permitted to have these kinds of ceremonies.

“After many years of being married, we are finally creating this book so that others could learn more about traditional Haida wedding ceremonies and to encourage ceremonies in the future,” Terri-Lynn explained.

Extensive research was required to piece together the intricacies of a Haida wedding as it was done before the impacts of missionaries and government legislation. The research included resolving discrepancies in the accounts of ethnographers and anthropologists, and consulting with Elders.

The very first step was to “seek wise counsel, talking to our families and Elders,” Terri-Lynn writes in the book. Her mother Mabel Williams had childhood memories of “playing weddings on the beach” and, in this way, her play became teacher and preserver.

We learn as children through playing, and we understand by imitating, the couple explained.

“So my mother, in enacting that [wedding ceremony] on the beach… it could be passed on to us today.”

Robert’s grandmother Naanii Florence Edenshaw Davidson had her life story recorded by anthropologist Margaret Blackman. Her wedding, one of the last of the traditional arranged marriages, took place in a church, but had preserved elements of the Haida way.

The Haida word for masks means to imitate or bring to life, so art has a role preserving culture, Robert said, but "we're also oral, so following the lessons of our ancestors as closely as we could to the information we got, it becomes the model."

The journey of a Haida Wedding

A Haida wedding is a sacred sequence of seven steps that involves careful planning, consultation with Elders, and a connection to ancestral wisdom.

The first steps include consulting with their clans, and that involved Robert asking permission to marry Terri-Lynn from her chief, as her father had passed. The significance in asking permission highlights the communal nature of a couple’s union. It not only involves families, but marriage also is the joining of their clans.

In collecting and organizing thousands of photographs of the wedding, Terri-Lynn chose powerful images for the book that captured the groom’s arrival to the marriage ceremony.

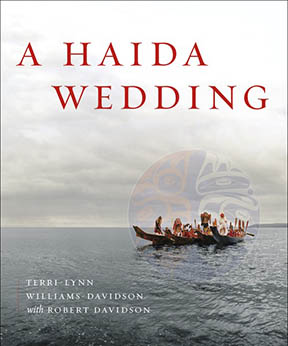

The groom, with matriarchs and paddlers, arrived in four grand canoes crafted by master carvers Bill Reid, Reg Davidson and Christian White. The canoes were large, ranging from 40 to 50 feet, with 12 to 15 paddlers in each.

The canoes and paddles were painted, with passengers in regalia. Platforms had been built into the prows of the canoes for dancers to stand upon, wearing full regalia and very large masks.

“A visual spectacle I’m sorry to have missed,” said Terri-Lynn, as she was already inside the hall waiting for their arrival.

The journey is done in silence, with only the sound of paddles dipping in unison, says Robert, making for a powerful procession, emphasizing the significance of the moment.

“The feeling was really amazing because you're traveling in silence,” he said.

When the travelers asked permission to come ashore, Robert's brother Reg danced a peace dance, and it was reciprocated from the shore.

“During the peace dance, we spread eagle down up into the air and it gently floats through the crowd and on the water, and it's really beautiful to see,” said Terri-Lynn.

At the wedding, traditional speeches were shared at length by clan members and Elders. Taking time to describe the achievements, talents and qualities of the bride and groom serves to illustrate the fitness of the match.

“To establish that we were of the same “rank,” said Terri-Lynn.

In Haida society “rank” is not determined by wealth, but by what people do for, and how they take care of, the community.

Part of confirming the marriage is the New Blanket Ceremony, with the couple walking to a cedar mat in the centre of the hall.

“Our aunties wrapped us in the blanket while we stood on the large woven cedar bark mat, then we linked our arms solidifying the marriage,” said Terri-Lynn.

Gifts to the clans, including a dowry to the bride’s family, were exchanged. Singing and dancing continued during the 12-hour celebration. Their ancestors would have spread the seven steps over 12 days.

Terri-Lynn danced with the same group she’d first began when she was a young teen,

“All of the kids who were part of my dance group now had their own children,” she said, “and we shared our dances that night.”

Robert danced with the tuul gundlas cyaal xaada, Rainbow Creek Dancers.

Innovating tradition

The hope that the couple has for A Haida Wedding is to document and preserve Haida marriage rites, holding it as law. “Held in the presence of our clans, witnesses and guests in a Haida feast setting, in other words, legalized in Haida law,” writes Terri-Lynn.

“There has been early case law in Canada going back to the 1800s that have confirmed that customary marriages are legal.”

As a lawyer, Terri-Lynn sees Indigenous peoples across Canada are “now in the process of recognizing our original laws as laws. They've been called ‘protocols’ and ‘traditions,’ but they're really law and they've been suppressed.” Not only through the potlatch prohibition, but also suppressing payment of dowries and the giveaways that happen at feasts. “All of those things were suppressed that legalized our ceremonies,” Terri-Lynn said.

“We're adding to that foundation. We've always been adapting. We weren't stuck in the past. We were always being innovative. We've always wanted to create awe. It’s that awe that comes from a foundation,” said Robert.