By Odette Auger, Windspeaker’s Buffalo Spirit Reporter

Elmer Ghostkeeper is a father, grandfather, teacher, philosopher, community leader, business person, knowledge keeper and scholar. He was born to parents Adolphus and Elsie Ghostkeeper at the Paddle Prairie Métis Settlement in Alberta in the 1940s.

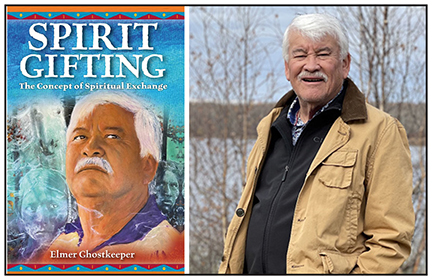

Ghostkeeper’s book Spirit Gifting, The Concept of Spiritual Exchange is dedicated, in part, to his parents, who he acknowledges for their spirituality and support. His knowledge of the “Metis way of doing things” started with them.

What makes the book Spirit Gifting particularly important is that we don’t often get access to the traditional and spiritual worldview of Métis people by Métis people. As expressed in the foreword of Spirit Gifting, penned by Dr. Wanda Wuttunee, professor, Native Studies at the University of Manitoba, “Insight into the Métis worldview is a topic that is rarely, if at all, handled from an insider’s perspective.”

Spirit Gifting, newly republished by Eschia Books, is about two worldviews, in fact. One honours the sacred connection between humans and other living beings—plants, birds, insects and animals—on Mother Earth. And the other values the material riches that come from exploiting the lands, void of that spiritual connection.

By examining the differences between living with the land as opposed to living off the land, from Ghostkeeper’s own personal perspective, Spirit Gifting speaks about a way of life and living that has been significantly impacted by that latter worldview. The latter sees the land as something to use and profit from rather than a sacred reciprocal relationship between living beings for mutual survival. That reciprocity recognizes the interdependence of humans and the environment.

Spirit Gifting, or Mekiachahkwewin, honours the reciprocity of all beings on Earth through spiritual exchange.

"When you ask a tree or an animal to sacrifice their life for our sustenance, we're doing a spiritual exchange because we give tobacco, we give a gift exchange. And so that relationship is what I call spiritual exchange," said Ghostkeeper.

“Spiritual gift exchange has three equal obligations,” he said. The first obligation is the giving by the donor. The second is the exchange between receiver and donor. And the third is giving thanks. Ghostkeeper gives an example of berry picking that begins by giving a prayer and asking for permission, the actual exchange, and ending with a tobacco offering or gesture of gratitude.

The concept of a spiritual exchange between humans and nature begins with recognizing the inherent spirituality in all living beings.

“Trees are living beings just like we are. And they have the four aspects that we do—spirit, emotion, mind and body.”

Understanding that relationship comes with a responsibility, said Ghostkeeper, and a directive from the Creator to respect and care for the Earth.

To understand the foundations of spiritual exchange, Spirit Gifting provides insight into the basic concept of Métis worldview, which Ghostkeeper says comprises of three worlds—the spirit world called kechi uske, this world, Mother Earth, or oma uske, and the evil world muchi uske. These worlds were created by the Great Spirit Kechi Manitow, who for the sake of harmony and balance in the universe created other spirits called achahkwak. They are Our Father, Our Mother, Our Grandfathers, Our Grandmothers and they have been gifted spiritual power to transform or shape shift. The Great Spirit also created, from the elements of the world, living beings—plants, animals, birds, insects and human beings.

Kechi Manitow also created spirit messengers who may appear in dreams who are also gifted the power to transform into good spiritual forces and bad. The dream spirits give the gift of life to living beings through the aspects of the spirit, mind and emotions, which complement the body, Ghostkeeper writes.

“The challenge for Métis people is to keep their aspect of the spirit, mind, emotion and body in harmony and balance. Balance of good and bad forces, within each person and in the universe, must be achieved if people wish to sustain and live a happy and healthy life,” Ghostkeeper explains. He shares where the food for the body is obtained and where the food for the mind, emotion and spirit is obtained.

The gifts that beings are given are acquired through the activities of ceremony, ritual and sacrifice, Ghostkeeper writes. The Métis livelihood is accomplished by adhering to these activities through a series of continuous relationships established by gift exchanges with plants and animals.

Up to the 1960s, Ghostkeeper’s family used this sacred worldview, which he describes in generous detail, and followed the Métis cosmological calendar to pattern their livelihood by living with the land. Spirit Gifting describes the Seasons of the Métis, from Goose Moon to Egg-laying Moon to Mating Moon to Eagle Moon.

“Natural signs signaled when to begin and end a seasonal round of activities of cleaning the land, planting and gathering, and harvesting both wild and domesticated plants and animals,” he writes.

In the 1970s, however, another worldview significantly begins to impact Ghostkeeper and the “Métis way of doing things” in his home community.

Development, Industrialization and Capitalism

Ghostkeeper was raised on the Paddle Prairie Métis Settlement, land chosen by a group of Métis men, including his father, and set aside under the Métis Population Betterment Act of 1938.

Ghostkeeper went to school with other Métis children on the settlement until Grade 9. For high school and beyond he had to leave the Settlement to continue his education.

Ghostkeeper attended the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology from 1966 to 1968, and graduated with a diploma in Civil Engineering Technology. His work kept him away from home until 1974 when he returned to the Paddle Prairie Settlement.

Upon his return he involved himself in community politics, elected to Settlement council for a three-year term. That time also coincided with exploration and development of a natural gas field in the region. In the winter of 1974–75, Ghostkeeper was employed by a multinational oil company as an assistant gas field construction supervisor, and the following year winter drilling programs were brought onto the Settlement.

Oilfield work had become his livelihood. His work involved clearcutting lands to construct roads to reach oil well locations, lands home to a wide variety of plants, birds and animals. This activity also interrupted those living with the land, like trappers.

In the section of Spirit Gifting titled “Living Off the Land,” Ghostkeeper describes the plans, work and heavy machinery that would transform the lands and bring economic development monies to the community. And that would transform the “Metis way of doing things.”

The older generations worked in the woods with their hands and draft horses. Feller Bunchers, and other mechanized equipment, removed people from the act of harvesting wood. People may notice a bear or a deer, but they are not seeing the woods more completely, the birds’ nests and the “eighty per cent of living beings in the forests that are invertebrates,” Ghostkeeper said.

"Rather than country foods, people started living with store bought, processed foods. And that created a lot of sickness. For example, diabetes and obesity.” Ghostkeeper said country foods come through effort, exercise, and work, so we are healthier and stronger when we are relying on hunting, fishing, berry and plant harvesting.

Oil field development in the region also challenged conflicting worldviews on such things as “ownership” of lands.

“Ownership (tipeyichiwin) to the Métis is viewed as a gift of collective stewardship for Mother Earth, a living being, from The Great Spirit (Kechi Manitow),” Ghostkeeper writes. In the opposing worldview “ownership is the legal right of dominion, possession and proprietorship…”

In his commentary after this section, Ghostkeeper acknowledges the push-pull of worldviews on his personal wellbeing.

“By making a living off the land through natural gas field construction… I had entered into a social relationship with the people with whom I worked, but not with the land and its plants and animals,” writes Ghostkeeper. “I had accepted an outside view of the land as an object.

“I had learned to make the personal and spiritual compromises necessary to influence oil company executives, contractors, Settlement councillors and businessmen. The concept of spiritual exchange had been repressed and had disappeared from my daily life.”

Ghostkeeper writes that turning his back on that sacred worldview resulted in “a dissatisfaction so intense that it stimulated me to attempt to revitalize my repressed worldview.” Through chapter four of Spirit Gifting, Ghostkeeper shares his path to his revitalization of the sacred worldview.

He tells Windspeaker that over-farming, excessive pollution, oil and gas development, and sports hunting have contributed to the impacts of the secular worldview on the territory, putting survival of all species at risk.

He gives, as an example, the commodification of bear and moose, with many millions of dollars earned annually from sport hunting.

“Spring is when the hunters from the U.S. come and hunt bear. As a matter of fact, I think the minister responsible for big game hunting in Alberta is spending a week in the States encouraging more hunting,” Ghostkeeper said. “Well, what are we going to leave for our seven generations?”

“It's not the Indigenous people that's creating endangered species, it's the non-Indigenous people that just can't see these are living beings. They have a right to live just as we do. They're breathing in the same moment we do.”

“All we have is to breathe in this moment. So are the animals breathing in this moment. Are all the people breathing in this moment? Nobody breathes an hour ahead of us or an hour behind us. We're all in this moment relative to where you're living. And I think when you're living in the city, you tend to forget that,” Ghostkeeper said.

“The western scientific worldview (is) where everything seems to be disconnected, unrelated and nature seems to be objectified.”

That thinking has directly led to the environmental damage caused by resource extraction and consumption of fossil fuels, he says. Ghostkeeper uses that industry as a stark reminder of the harm we inflict on the Earth when we live “off the land,” a sector he has experienced firsthand.

The toxic tailing ponds in Alberta “are way under-designed for the sludge. They’ve been leaking for years,” said Ghostkeeper. A recent Financial Post article reports that Alberta’s environmental liability for thousands upon thousands of oil and gas wells has been grossly underestimated, with a total cost to clean them starting at $88 billion. “If they ever could,” Ghostkeeper says cynically.

These companies, he says, “don't care about what they do to the land. They're living off of it. When the oil companies are done taking everything they could, they just walk away. So who's left to clean it up?”

Ghostkeeper says transitioning to renewable energy sources and reducing our carbon footprint is essential for a sustainable future.

“We just can't do this anymore. We’ve got to shift away from fossil fuels.”

Ghostkeeper says Earth is using climate change to cleanse herself from industrialism.

"Mother Earth will heal itself. Well, that's what she's trying to do now by all the fires and the wind and the flooding and the hot temperatures,” says Ghostkeeper. If the resource extractors won’t stop damaging Earth, she will remove their ability to live off the land to protect herself.

“Mother Earth is going to stop it, because anything manmade, like capitalism, has a beginning, a middle and an end. There's an excellent book written by Dr. Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti called Hospicing Modernity,” Ghostkeeper says. “This age we're living in, modernity, we can't sustain it. The top one per cent is becoming richer and the bottom of us, we're struggling. Affordability is a big issue. Can you afford the food? What about the rent? It's getting to the point where people just can't afford to live anymore.”

“Young people are realizing we just can't continue with this lifestyle,” says Ghostkeeper. He believes living with the land is still a possibility.

The Importance of Prayer

Ghostkeeper's book emphasizes the importance of prayer in the context of reconnecting with the land and for stewardship. He explains that through prayer we can gain a deeper understanding of all Earth’s inhabitants as equal living beings.

Ghostkeeper suggests we start every day with an hour walk outdoors. He reminds us of how unhealthy stale, indoor air is and how we need to remember we are breathing the air of today, not yesterday and not tomorrow.

He explains we can feel more connected to Mother Earth just by being outside. By touching plants, we will be more connected and be “with the land.”

“I was taught that the best time to pray is when you're out walking on Mother Earth,” Ghostkeeper said. “I walk every morning. I walk a mile and pray.”

“There's not that many people in cities, I’m thinking of Indigenous people, that go for a walk every morning and pray. They're so rushed.”

“One of the great thinkers, Einstein said, ‘you know what gets people out of bed every morning? The fear of not having money in this capitalist system. Whether you're sick or not, you have to get up and go to work, earn the money to be able to pay for your livelihood." Ghostkeeper says people “just don't have time to really stop and think about what I'm talking about.”

The reality for most is the start of their day means a commute, Ghostkeeper says.

“Every time you jump into your car and turn on the motor, what are you spewing into the atmosphere? Carbon monoxide, poison.”

Ghostkeeper is active with grassroots environmental groups focusing on watershed conservancy. Through this work, he sees projects and initiatives that make him feel hopeful for the next generation.

“A lot of the young people want to know about medicine plants like rat root and spiritual diamond willow fungus, chaga, stuff like that. And I'm really happy that the young people are starting to revitalize their traditional methods rather than this modernity, because it's going to end and we have to adapt back to living with the land.”

Ghostkeeper has advice on how to continue moving forward in a good way.

“You have to steward the land. That's our responsibility. Then you have to use ki-sâk-ihitin, love, rather than fear and ask Creator. Pray.”

“That’s going to save us, I think.”

Spirit Gifting, The Concept of Spiritual Exchange is available to order from Eschia Books at https://www.canadabookdistributors.com/product/13909/

(Editor’s note: Elmer Ghostkeeper is a member of the board of directors of the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta, publisher of Windspeaker.com.)