Having guests over was uncommon, living off grid in northern Saskatchewan, but it was on those occasions when author and artist Arnold Isbister heard the stories of the Little People.

“Lit by kerosene lamp and wood cookstove,” Isbister said he would sit in the corners and listen to the adults at the table tell stories, and those stories planted the earliest seeds for his book Samuel and the Little People.

“My mother would tell stories and she knew of people who had seen them,” the author from the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation recalled.

Hines Lake is long, “around eight kilometres long,” said Isbister.

“We’d get in the boat and go to the very end to visit Mrs. J. She didn't keep it a secret or anything. Little People were there all the time. They played with her, and they’d bring her stuff, and she, in turn, would accept them.

“And then she would talk with them and then cook little things and give them things in return. Little beads and different craft work that she would make.”

Stories of Little People are widespread throughout Indigenous cultures.

“It's an established fact of different nations, around here anyway, that there was—and there still are—Little People,” Isbister said.

“We just accept them, and you hear stories of them. We take them as fact. So there's no feeling of shame or guilt about me telling the stories,” he said.

“And then a lot of the stories are fictional, and everybody kind of understands that at the same time. Maybe they're real. So it's complicated. It’s kind of an enigma in our culture of how different people perceive them.”

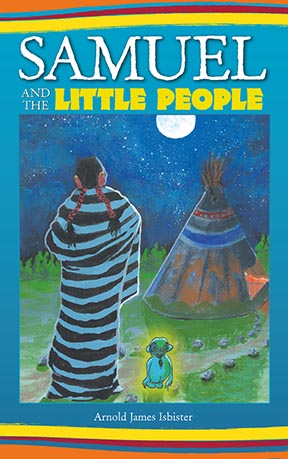

In Samuel and the Little People, Isbister plays by blurring the lines between myth and fact in his author’s statement at the beginning of the book. In it, acting as the book’s narrator, Isbister tells a story about going through some old belongings of his deceased grandfather where he finds a journal written in Cree syllabics by an ancestor named Samuel White Wolf.

It was a name that was mentioned often by family, but never in connection with stories of Little People, Isbister writes. He says when he transcribed the syllabics into English, White Wolf’s encounters with the Little People were revealed.

Samuel and the Little People, which was published in 2021 by Eschia Books, a small Indigenous publisher based in Alberta, is kicked off with a fascinating foreword by acclaimed author of Halfbreed, Maria Campbell, who shares her own stories of Little People.

She writes at the end of the foreword, Enjoy Arnold’s stories. They are miyo âcimowinamiyo, good stories; and miyo maskihhkiy, good medicine.

As Plains Cree, Isbister was introduced to the Little People as trickster characters.

“They are good, but they can be mischievous,” Isbister said.

“People are kind of fearful of them, but yet when they see what they do, or hear of what they do, they accept.”

But he warns “You have to be always on guard of what they're doing, what they're saying to you.”

Sometimes Little People come as helpers. They could bring teachings, too, Isbister said.

“They may be bringing you a lesson in a mischievous way, so you have to always be cautious about them. But then once you're their friend, they teach you all the good things.”

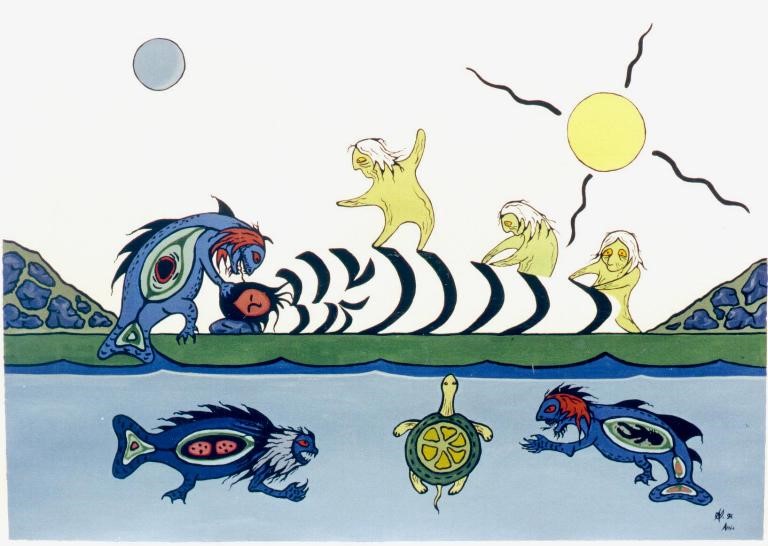

When people describe Little People, they say they are various tones of blue-green, some with hair, some without.

“They look kind of old. They would have some wrinkles on their skin, their face and their body. They were small and kind of stubby,” Isbister said.

They can be heard singing or playing. People leave small gifts for them in the places they have been seen, so the little people would think favourably of them, as good people.

When they accepted gifts, Little People might also leave some.

It’s their large, dark eyes that capture Isbister’s imagination.

“They say when you looked into their eyes, you felt like you were part of that little person,” he said. “When you look at them, they could see into you, what kind of person you were and what was your emotional and mental state. They knew that already, and they were all knowing.”

He said it was important to note that other language groups, other nations, describe Little People differently.

Isbister grew up to be an artist, but has also worked with at-risk youth, in the fields of education and training, human resources, and economic development.

It wasn’t until he retired that he turned his full attention to writing. His other books include Stories Moshum and Kokum Told Me and Strange Bannock.

Stirbugs and Screws is derived from his work at a psychiatric centre within the penitentiary system.

Once he was an Elder himself, people who heard his tales asked, ‘Why doesn't anybody do any stories on them?’

“So that kind of inspired me,” he said.

Samuel and the Little People was shortlisted for the Children’s and Young Adult Book of the Year awards by the Book Publishers Association of Alberta.

Dianne Meili (Métis) was one of those who asked for the stories. She’s the president of Eschia Books.

As a journalist and editor, her “heart work” was in listening to Elders, more than doing the political news stories. Meili has a long association in working for, and with, Windspeaker.

“I would just want to follow the Elders home and learn from them,” she chuckled.

She made that dream come true, spending two years gathering stories and wisdom of the Prairie’s most beloved Elders for the book, Those Who Know, published in 1992. An updated version in 2012 won the Trade Non-Fiction Book Award at the 2013 Alberta Book Publishing Awards.

Meili has heard Elders sharing stories of Little People, too.

“I've heard one story of an Elder looking out into her backyard and it was raining. But in the corner of her yard were these little people around the fire acting like it wasn't even raining. They were in this little pocket or bubble of reality. So, I think we just get these peeks into their dimensional world.”

For Isbister, it’s important to address the lack of stories about Little People today. He’s been in culture sharing groups where people knew there were stories about the Little People but hadn’t heard any.

The Little People Isbister heard tales of were associated with the elderly or the very young.

Meili thinks a more receptive mind is why young children can see them, “because they don't have blockages against the magical like we do, where we get more logical as we age.”

Isbister was taught, “they also bring comfort when in need, when (people) get older and they're by themselves or they're sick,” he said.

“Or maybe they had a traumatic experience in their life, and then the Little People come to them and offer comfort,” Isbister said.

“We hoped that (the book) would be taken in the spirit of Indigenous ways of knowing, which go beyond that which you can touch, beyond the five senses,” said Meili.

“It's so important to tell our stories in the way that we know them.”

To get a copy of Samuel and the Little People visit https://www.canadabookdistributors.com/product/samuel-the-little-people/

Editor’s note: Perceptions of Little People differ between Nations and groups. In a story from Dr. Anne Anderson, published in Windspeaker in 1988, she uses a Cree word for Little People, memekwesiwak, to describe mermaids.

Mémékwésiwak are described as a “water-related spirit being, the little rock people” in the thesis titled Water, Dreams and Treaties Agnes Ross’ Mémékwésiwak Stories and Treaty No. 5.

Read more about this and Dr. Anderson’s story here https://windspeaker.com/buffalo-spirit/why-fish-disappeared-fishermens-nets

For another Little People story about the time they healed a severely injured Cree warrior, visit https://windspeaker.com/canadian-classroom/gift-little-people

**************

Windspeaker is owned and operated by the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta, an independent, not-for-profit communications organization.

Each year, Windspeaker.com publishes hundreds of free articles focused on Indigenous peoples, their issues and concerns, and the work they are undertaking to build a better future.

If you support objective, mature and balanced coverage of news relevant to Indigenous peoples, please consider supporting our work. Whatever the amount, it helps keep us going.