Art can teach us a lot about Indigenous worldview. It sparks discussion and we can share our stories by sharing our thoughts about an artist’s work.

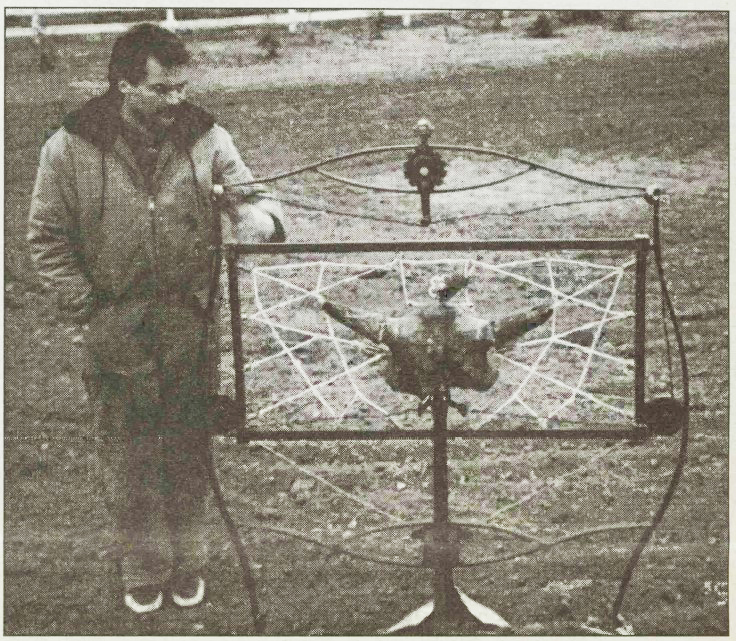

Such was the case back in 2000 when an artist brought his work into the offices of the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society in Edmonton. The artist had created a large stand of metal and the work had been made to resemble a dreamcatcher that had been woven with barbed wire. At the centre of the barbed wire was a Buffalo skull.

In an interview with reporter Yvonne Irene Gladue, the artist claimed that some people found his work offensive. The artist’s intention was to represent the fences that cattle ranchers had put up around their properties, which inhibited the movement of Buffalo and forced them away from their natural habitat to other feeding areas.

He said he wanted people to think about the steel and machinery that changed Indigenous people’s way of life forever.

“The Aboriginal people had to start relying on cattle for food. They no longer hunted. They had to buy from the cattle farmers,” said artist Ivan Lord, who was born in Fort Smith, N.W.T., and who had recently learned he had Mohawk ancestry.

Ivan’s work did cause quite a discussion in the office at the time about the use of the Buffalo skull in the work and, by extension, the use of other spiritual material in art.

Buffalo skulls are important in Indigenous culture. They are used in Sundances and in sweat ceremonies. There are two kinds of skulls, from the flesh and from the ground.

Staff at the time, Gloria Stonechild and Norman Quinney, sought out some advice. Comments on the work were sought from cultural advisor Devalon Small Legs, artist Dale Stonechild and Elder Ken Gopher.

Small Legs (Peigan/southern Alberta), explained the kind of skull that Lord had was from the ground.

“That’s the one that is very sacred to us. That’s the one that needs to be taken care of in a very, very respectful manner, primarily because the Buffalo spirit is still there and it needs some tobacco. It needs some offerings. The one that’s taken from the flesh, the ones that are slaughtered and sold, they can be displayed.” But still, they need to be respectfully used, said Small Legs.

Quinney, a Cree man from Frog Lake in eastern Alberta, said when you find such an object as a Buffalo skull, you should first get an Elder to put tobacco down and have a prayer and then it can be removed from the spot where it is found. “That’s what I was taught,” he said.

Going through protocol will lead an artist to be guided by the spirit and directed how to use such sacred material, said Small Legs.

Dale Stonechild, (Cree/Sioux), said that while he understood the statement the artist was making, he got scared about the Buffalo skull’s use.

“I feel that this sacred object should not be displayed in such a, almost, gross form… I see these sacred Buffalo skulls at the sweatlodge, at the Sundance. And when I look at it in this context, it is totally absurd, because I know that the spirits of these magnificent animals, they have a place in traditional society that is very highly respected and honoured.”

Ken Gopher, Chippewa/Cree from Rocky Boy Agency in the U.S., said the Buffalo is a spirit. “We have to treat the Buffalo with holiness because he was created for us to be our provider on Mother Earth… He’s connected with the Sundance. He is really a holy thing, next to a Thunderbird. It’s their partner.

“All these things that’s connected with the Sundance, the Thunderbirds, the Buffalo, we have to really respect that Buffalo skull… You’ve got to have a lot of respect for it. That’s like trying to put barbed wire on a Thunderbird, which could never be…

‘We pray to that Buffalo. We pray to the Thunderbirds. We pray to the Sun and all these things that are connected with the Sundances. And I, myself, I’m really scared of stuff like this.”

Small Legs also spoke of the need to respect all the items of the Sundance.

“The two very sacred items that we have is, first off, the centre pole… where the lodge is bult towards and people make pledges to dance toward the Sundance centre pole. The other most significant is the Buffalo skull.

“The Buffalo skull is very sacred. It represents the Buffalo grandfather that comes and helps us, gives us our food, gives us our way of life. That item, the Buffalo skull, if the individual putting the Sundance up doesn’t have one, then he can’t put up a lodge for the Sun. If people understood the significance of these items that they find, they would have a better understanding and lot more respect for the item itself.

Small Legs said he had no intention of being critical of the artist, because Lord was just learning about his own Indigenous ancestry.

“He doesn’t have the teachings with him, and he went about doing this piece on his own. And then, only after that, did he seek Native advice on how they felt about it.

“If he’d done the opposite and asked an Elder to come and look at the Buffalo skull, he could have possibly got a different idea. Or if he understood how significant the Buffalo skull was, I believe he would have gotten a different idea of how to put together the art piece…

“It takes a protocol process with tobacco. If somebody wants to find out about these things they have to come together and ask the questions that need to be asked with tobacco.”

Quinney said when you want to approach an Elder you have to take tobacco and cloth.

“There are four cloth colours the northern people go by—red, yellow, green and white, and matching ribbons—and you go to an Elder and ask him and he knows you’re after something and he’ll advise you.”

Small Legs said if an Elder doesn’t have an answer to a person’s question, it would be that Elder’s responsibility to say so and help pass you to someone who would know.

Dale Stonechild remembers advice he got from an artist when he was starting out. “Always know your subject matter.” He acknowledged that he was critical looking at Lord’s work. “I realize the statement is a meaningful statement, however, the object. I see this Buffalo skull has to be taken care of.

“When you find an Eagle feather or an Eagle bone, something that is sacred, when you find an animal beside the road, my grandfather told me, ‘Take it away from the road and put some tobacco down for it and let it go free where it belongs.’ I see the spirit of the Buffalo captured inside this little frame and that is no place for him. He has a place to go.”

Editor’s Note:

Readers may find this additional Buffalo Spirit story helpful to understand the Sundance a little better and the role of the Buffalo skull in the Sundance. https://windspeaker.com/teachings/buffalo-spirit-sundance-is-the-ceremo…

Also, shortly after his visit to the Windspeaker office and our interview about his work, Lord decided to remove the Buffalo skull from the centre of the barbed wire.