Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

The Moose Hide Campaign is gearing up for its tenth anniversary with an upcoming livestream and set of virtual workshops.

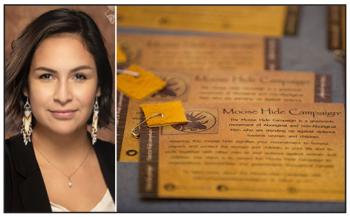

Founded in 2011 by a then 16-year-old Raven Lacerte and her father Paul, the campaign has now distributed more than two million squares of moose hide pins, representative of the commitments made during the campaign’s decade-long effort to end violence towards women and children.

While out on a hunting trip near the Highway of Tears in northern British Columbia, called as such because of the many women who have gone missing or have been murdered along that 725-km stretch of Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert, the father-daughter duo began thinking of the White Ribbon Campaign.

Co-founded by former federal New Democratic Party leader, the now late Jack Layton, the White Ribbon Campaign was sparked in response to the hate and violence that led to the shooting deaths of 14 women and others injured at École Polytechnique in Montreal in 1989.

“As we were talking about it, this moment of inspiration came to us,” Raven said. “We thought that moose hide would be something that men and boys would feel connected to with a hunter-gatherer, warrior feel to it,” she said, and that in turn could help raise awareness about the issue of violence toward women and children in the Indigenous community.

Paul Lacerte had been at a conference in Vancouver focused on ending such violence when he recognized how few men were engaged by the issue. Of the hundreds of attendees, Lacerte noticed less than five men taking a true interest.

“Women were doing all of it, the advocacy, the support, bearing the burden of the trauma and the healing,” Raven said.

“We’ve been learning and growing over the years, as you can probably imagine as a 16-year-old and her dad just trying to sort it all out,” Raven said of the Moose Hide Campaign’s development over the years.

“When we started, our idea was that ‘men need to end violence towards women and children’, with a special focus on Indigenous women and children,” Raven said.

“As visibly Indigenous people, we know that the likelihood of something bad happening to me is much higher than other people. My dad really wanted to do that work to ensure that myself and my sisters could live lives free from violence.”

Men and boys soon became engaged in the campaign, which includes a fast for one day as part of a call to action, which tests and deepens an individual’s personal commitment to honour and protect the woman and children in their lives.

There was also a strong interest from other participants across the gender spectrum.

“Immediately, women and gender non-binary folks were asking what their role could be in this movement,” Raven said.

“It’s an awareness campaign. We invite everyone to wear the moose hide pin and fast with us, and continue these really important conversations.”

“We’re still targeting men and boys specifically, but in the same breath saying that this campaign is for everyone. We need all of us to work together to end violence against women and children.”

Raven also emphasized a greater integration of trans people and members of the greater LGBTQ2S+ community, with a goal of bringing an end to all gender-based and domestic violence.

An event planned for Feb. 11 will run from 8:30 a.m. to 11:45 a.m. Pacific Time. The intention is “To remember those we have lost. To share our stories and struggles. To grow closer through the experience of fasting and ceremony. To motivate one another with all we have managed to achieve,” reads the Moose Hide Campaign website.

Forced online due to restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the event offers the opportunity for attendees to hear from keynote speakers, the campaign’s founders, Elders and to participate in ceremony.

February 11 is also the day people will undergo the traditional fast, which offers the opportunity for humility, healing and a signal that those taking part are serious about making change.

Raven emphasized the importance of signing up through the campaign website to register for the day’s events, order a set of pins, learn healthy fasting techniques, and tips on organizing local Moose Hide Campaign events. There is also an option to order non-leather pins for those interested.

Lacerte emphasized that the moose hides come from a variety of sources that are sent to a tannery, including donations from hunters who otherwise would have left the hides in the bush.

“No moose are killed solely for the purpose of the campaign,” Raven said.

The campaign encourages participants to wear the hide pins year-round.

“Moose are iconically Canadian,” she said. “We wanted to offer a bit of the beauty and love and healing energy of the land as part of this movement. This is not just something you can throw in the garbage. We want you to wear it with pride.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.