Image Caption

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

“I belonged to a community,” said Ken Carriere.

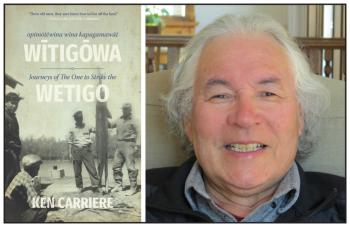

That belonging is clearly shown by the first-time author in his memoir Opimōtēwina wīna kapagamawāt Wītigōwa/Journeys of The One to Strike the Wetigo, which was released in mid-November.

Carriere sets up that community right from the start in his six pages of acknowledgements and it continues through in the tales he recounts of days living and trapping, fishing and hunting in the upstream region of the Saskatchewan River Delta.

It’s not nostalgia, though, he says.

“Nostalgia to me, sounds to me, like all of a sudden you enjoyed something at one point in your life and then you think, ‘I’d like to have that again.’ But in fact, this thing about going out on the land just continues for me,” said Carriere, a member of the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation in northeastern Saskatchewan.

He proudly announced during his interview with Windspeaker.com that he had recently been moose hunting in northern Quebec with friends.

Carriere casts his father Pierre, a Second World War veteran who served in Europe and returned home with his face disfigured, in the light of many young boys—a hero.

On Sept. 15, 1944, Pierre Carriere was believed dead when a bullet entered his face, shattered his jawbone and continued through the back of his neck, just missing his vertebrae. He lay still on the battle ground to fool the sniper. But then he passed out. He awoke when they were putting him into a body bag.

The title of Carriere’s memoir, Journeys of The One to Strike the Wetigo, comes from his father’s assessment of him. When Carriere was about 10, his father told a friend that he had brought his young son along on the boat trip “to strike the Wetigo.”

Carriere had been told about the Wetigo by his mother. She said that the creature came out at night and stole children who were outside. The Wetigo, Carriere believed, would do the “cruellest and most horrible things imaginable.”

And his father had said young Ken would be their protector.

“When I was a kid I didn’t really understand what he’d done. All I knew was he was our dad. He needed helpers. He’s got me now. I’m it. That sort of thing…We just helped him along. We know he’s going to teach you a few things and you learn as you go along,” said Carriere.

While his father taught him how to live off the land, Pierre also encouraged his son to get an education.

“He pushed me in that direction. Both my parents did,” said Carriere, who became a geologist and an educator.

However, it’s being a writer he takes the most pride in.

“I always wanted to be a writer (from) when I first started reading Canadian literature in my dad’s warehouse,” he said.

The warehouse was a log building where implements were stored right along with a “pile of books” from family friend and Métis activist James Brady.

It was at that time that a young Carriere read an article in the weekend edition of the Winnipeg Free Press by journalist Tom Alderman called “A cold hard way to make a measly buck.” It was about Mikisew Cree First Nation Elder Napolean “Snowbird” Martin, a trapper, a fisher, a boat builder and a cabin builder. He lived along the Athabasca River in a place still known as Snowbird’s Settlement.

“I read about that story and it just swung into my head like you wouldn’t believe. I just loved that story so much and it stayed with me for a very, very long time. I even acknowledge it in my book. That’s how I got started in wanting to be a writer,” said Carriere.

Carriere is a fluent Swampy Cree speaker and part of his memoir includes interviews he conducted with his aunts so that “people would believe there was such a person as my dad who actually came back from the dead.” The interviews are presented in both English and Swampy Cree.

“I felt, I’m saying we’re Cree Indians. To make it believable. Yes, we are Cree Indians. That’s who we are. Our language is the Swampy Cree,” he said.

As for the adventures he presents in his memoir, Carriere says he hopes when city dwellers read about them, they will want to seek out wilderness areas that are close by.

“Being connected to the land that gives us our spirituality. I guess that’s where it belongs, the connection to the land…your spirituality is the most deepest feeling you can have…It’s your humanity that jumps up at you,” said Carriere.

Opimōtēwina wīna kapagamawāt Wītigōwa/Journeys of The One to Strike the Wetigo is published by University of Regina Press. It is available on numerous book sites as well as uofrpress.ca/Books.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.