Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

“When the price of groceries have gotten more expensive, every bottle of water I buy means less food to put on the table. It’s hard and it’s not fair, especially when my neighbours in the City of Calgary live less than five kilometres away and have full access to clean drinking water and never have to worry about running out or telling their children to be mindful of their water usage,” said Kylie Meguinis of the Tsuut’ina Nation in southern Alberta.

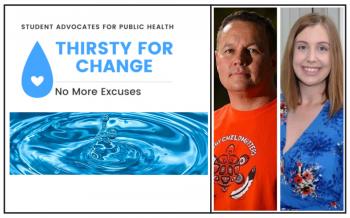

It's real-life stories like that of Meguinis that the Student Advocates for Public Health (SAPH), comprising graduate students from the University of Alberta hope will spark both conversation and change when it comes to safe drinking water in Indigenous communities.

SAPH hosted a press conference and public forum on March 22, World Water Day.

Meguinis says she was telling a similar story one year ago when washing hands and keeping surfaces clean were the primary ways to fight the coronavirus pandemic. It was a challenge then, she says, with 10 people living in one home. Even now it remains a challenge.

“I still have to remind my children to limit their water for both bath and showers. I still spend hundreds of dollars a week on bottle water and trips to the laundromat,” she said.

SAPH member Alexa Thompson says while she was aware that not all Indigenous communities had access to safe drinking water, she didn’t know what she could do to fix it.

“It wasn’t until I heard from people with lived experience … that it really hit me… And I think education is important but so is hearing from the Indigenous voices that live in these communities and what they have to go through on a day-to-day basis. And if we want to educate the public, we have to put Indigenous voices out there for people to be aware of what’s going on,” said Thompson.

According to figures provided by SAPH in its “Thirsty for Change” position statement, as of Jan. 26, 2021, there were 57 long-term drinking water advisories in place for 39 First Nations across Canada with 54 per cent of those communities having an advisory in place for longer than 10 years.

Randal Bell, also a member of SAPH, says now is the time for collaborative efforts and public voices to bring about the necessary changes in government policy.

“There’s been a fundamental change in (the) Canadian public. I really believe that Kamloops and Cowessess and the graves of these children, the voices of these children, I really believe they’ve been heard,” said Bell, referencing the unmarked graves uncovered at the former Kamloops Indian residential school (Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation) and at Marieval residential school (Cowessess First Nation) last spring.

“And I really believe that they’ve woken a sleeping giant in the Canadian consciousness. And a I really believe … there is a more empathetic response to things Indigenous, there is more desire and appetite for change,” said Bell.

Dr. Kerry Black, a Canada research chair of integrated knowledge, engineering and sustainable community and an assistant professor of engineering at the University of Calgary, spoke as part of SAPH’s panel. Black’s research area also includes sustainable water management.

There are many challenges to improving water on reserves, she said, not the least of which is the colonial approach where solutions are dictated by the government and there is chronic underfunding of infrastructure.

Black said a collective response was required from municipal, provincial, territorial and federal governments.

Black said she is encouraged by the safe drinking water class action settlement that was signed in December 2021 with the federal government. The settlement covers First Nations and their residents who were subject to a water advisory for at least one year between Nov. 20, 1995 and June 20, 2021. Those numbers currently sit at around 250 First Nations and 140,000 on-reserve individuals, but are expected to climb.

“What makes this really, really different is the fact that … it’s a legal document … (and) no matter who’s in power is required to address what’s in that settlement agreement,” said Black.

She also points out that the settlement addresses the true costs of fixing water systems and makes it an Indigenous-led process.

The settlement also creates a First Nations Advisory Committee on Safe Drinking Water, supports First Nations' efforts to develop their own drinking water bylaws and initiatives; and calls for the modernization of Canada’s First Nations drinking water legislations; or the creation of a First Nations Advisory Committee on Safe Drinking Water.

“As the federal government begins rewriting this legislation, SAPH hopes its voice, along with the voices of all communities across Canada that are currently without sustainable clean drinking water, will be reflected in the legislation. SAPH encourages the public to make their voice heard too,” says the organization in a news release.

“You can write your provincial MLAs. You can write your federal MPs. And you can demand that they, too, stand in solidarity with those seeking to address Indigenous water inequity. You can tell them that you’re part of the 97 per cent of Canadians that believe water is a fundamental human right. And finally you can tell them the time to address Indigenous water inequity in Canada is now,” said Bell.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.