Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

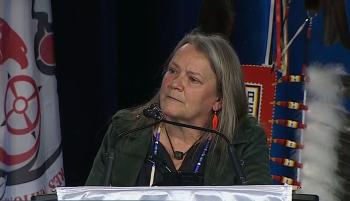

“Anywhere where the truth takes us that kids are buried” are the sites that will be searched, said Kimberly Murray, the independent special interlocutor for Missing Children and Unmarked Graves and Burial Sites associated with Indian residential schools.

Those sites include the Indian residential schools not recognized in the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, Indian hospitals, reformatories, and sanitoriums, Murray told chiefs Dec. 6, the first day of the Assembly of First Nations’ Special Chiefs Assembly in Ottawa.

“The very same survivors that tried to get these institutions on the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement, are now raising concerns about burials at those institutions,” she said. “Inevitably, it’s on that list. So there’s hundreds and hundreds of institutions in addition to the residential schools.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission on the legacy of Indian residential schools dedicated one entire volume of its final report to missing children and unmarked graves. The commission identified 3,200 deaths of students, both named and unnamed. That list was only the start, said the commission, and the work needed to continue, which it directed in its Calls to Action.

Murray, who is Kanien'kehá:ka from Kanesatake, Que., received a two-year mandate as the independent special interlocutor on June 8 from federal Justice Minister David Lametti. Her appointment followed approximately one year after unmarked graves were located first at Kamloops Indian residential school (215 graves) in Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation and then at Marivel Indian residential school at the Cowessess First Nation (751).

She is working with a $10.4 million budget over the two years.

Murray outlined to chiefs what she included in her first progress report to Lametti, submitted in mid-November.

She has met with a number of communities and all shared concerns over common issues.

There is insufficient funding in a wide range of areas, from mental wellness and community well-being to carrying out the searches. Murray said she has raised this concern with Lametti and Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller numerous times.

There is also a “massive delay” in analysing the data collected from ground searches, said Murray. She pointed out that there are few experts in the country who know how to analyse the data for burials. That work, she stressed, is different than analysing for pipelines and utility lines.

Communities are also having difficulty accessing land to do searches, with private landowners “creating barriers,” she said. Negotiations are underway in some situations to get that access.

“That’s the problem with our law. We don’t have a law that grants access to these lands,” said Murray.

Access to records is difficult, whether from Library and Archives Canada, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation and various church entities. There are delays in getting the records and “people doling out pages to you one page at a time,” she said.

Justice and accountability are also common issues.

“Why would we rely on the institutions that took the children away? Is there another entity that can come in and do proper investigations? How do we hold people accountable, especially if they are all deceased?” said Murray.

She added that the International Criminal Court doesn’t have jurisdiction because it was created after the residential school deaths.

Murray’s mandate is restricted in that she has no powers to compel records and she cannot interfere with criminal investigations, prosecutions or civil proceedings.

Chief David Monias of the Pimicikamak Cree Nation said “international intervention” was required because Murray’s mandate had been established by the “murderer.”

“The international committee on missing persons should have been involved in this case. They do that all over the world for other countries where people are massacred or missing,” said Monias.

Murray said she did have plans to meet with International Commission on Missing Persons, However, she added, she was wary about the work they did and didn’t want them treating families and communities as an afterthought.

“Before I want to say I want to stand behind them, I want to make sure they know how to incorporate Indigenous protocols and Indigenous law into their work because I’ve been looking at what they’ve done to date and it’s very colonial,” she said.

Murray has hosted gatherings in Edmonton and Winnipeg. Gatherings are planned for Vancouver, Toronto, Quebec and the north in the new year.

She is scheduled to file her interim report next June. Her final report is scheduled for the end of her mandate and is to include recommendations relating to federal laws, policies and practices.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.