Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

There needs to be a new way of thinking in order to advance the prosperity of Indigenous people living in urban centres.

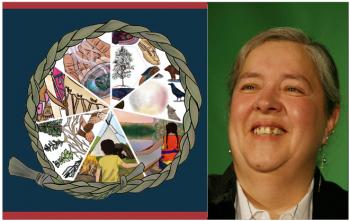

That is one of the main messages from a comprehensive report released by the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres (OFIFC).

The report is titled Ganohonyohk (Giving Thanks): Understanding Prosperity from the Perspectives of Urban Indigenous Friendship Centre Communities in Ontario.

In order to advance the prosperity of Indigenous urban dwellers, new culturally-centered programs and services are required, the report concluded after three years of research.

And in order to improve economic and social benefits to urban Indigenous peoples, a shift from poverty reduction to cultivating prosperity is required.

“We’ve worked for a very hard time to make changes,” said Sylvia Maracle, OFIFC’s executive director. “But there’s a large portion of Ontario, and in Canada, who see us through a lens that the glass is half empty. That we are poor.”

The report determined that any new approaches implemented must be culturally appropriate and specific to certain communities, and that friendship centres have vital roles as community hubs and must promote the required shifts in thinking.

The OFIFC represents a total of 29 friendship centres across Ontario. The centres provide a place for Indigenous people in urban locations to gather, connect with others and receive culturally-based services.

“In some communities, friendship centres are the largest employer of Indigenous people,” Maracle said.

Four key themes that can help assist in the shift of thinking and service delivery were identified: restoration of identity, a sense of belonging, Indigenous ways of knowing and everyday good living.

The report followed extensive research at seven Indigenous friendship centres across Ontario—Kenora’s Ne-Chee Friendship Centre, Ininew Friendship Centre in Cochrane, Fort Frances’ United Friendship Centre, Toronto’s Council Fire Native Cultural Centre Inc., N’Swakamok Native Friendship Centre in Sudbury, Fort Erie Native Friendship Centre and Windsor’s Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre.

Maracle believes an accurate picture was achieved despite consulting less than one quarter of all of the friendship centres in the province.

“We feel it’s a good representation,” Maracle said. “We did try to do geographic tests and get both large and small centres in different parts of the province.”

It’s no secret urban Indigenous communities are a vulnerable population, with a greater chance than other groups of experiencing poverty at some point.

More than half (53 per cent) of urban Indigenous single people live below the poverty line. And almost one third (29 per cent) of urban Indigenous families are in a similar situation.

Also, substantial resources are required to offer programs as there is a growing Indigenous demographic. Statistics Canada shows that more than 80 per cent of Indigenous people in Ontario live off reserve. And about 62 per cent of those reside in urban locations.

Besides interviews, the report findings were based on focus groups and participation in cultural events.

A main focus of the research was to engage with Indigenous community members to see how they view a prosperous or wealthy life.

“I was surprised by the diversity in large and small centres,” Maracle said. “They could define their prosperity with some consistency.”

Maracle said research determined Indigenous people want to get a message out. They want to show people who they are and what they have as prosperity.

“In Toronto they defined what sort of things they are grateful for,” Maracle said. “And in Cochrane in northern Ontario, their notion of prosperity came not from money... It came from the land for them and their connection to the land.”

The changes required, as laid out in the report, correspond to various calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

This includes Call to Action Number 7, which calls on the federal government to form a joint strategy with Indigenous groups in order to eliminate educational and employment gaps between non-Indigenous and Indigenous people.

Another is Call to Action 92ii, which stresses that Indigenous people must have equitable access to jobs, training and educational opportunities in the corporate sector. This call to action also states Indigenous communities should gain long-term benefits from economic development projects.