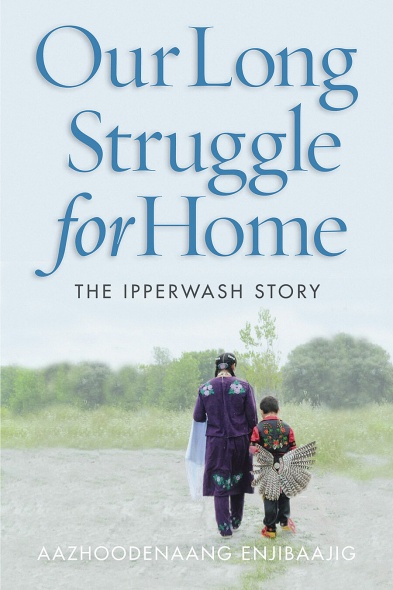

Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Kevin Simon was 18 years old in September 1995 when he helped his cousin Anthony “Dudley” George move picnic tables into the sandy parking lot of the Ipperwash Provincial Park to serve as a blockade to the park’s entrance.

Shortly after, Dudley George was shot by the Ontario Provincial Police.

Simon is in his mid-forties now and admits that “a lot of stuff I thought I had dealt with and overcome” surfaced as he and other Aazhoodenaang Enjibaajig/Nishnaabeg of Stoney Point told their story in the new book, Our Long Struggle for Home: The Ipperwash Story.

“I came to realize I still had a lot of stuff to deal with,” he said.

“There are days I still have trouble getting pulled over by police, just knowing that even a RIDE (Reduce Impaired Driving Everywhere) check, (can be) a flashback to that night.”

“That night” is the pivotal event in Our Long Struggle for Home. It’s the night that the OPP moved in and fatally shot Dudley George and severely beat Bernard George in the parking lot of Ipperwash Park.

Stoney Pointers were there to occupy their land that had been appropriated by the federal government to use as a military camp and never returned to Stoney Point as promised.

The tragedy of that night is underscored by how that section of the book is structured. The events of the shooting are told by a combination of first-person recollections from Stoney Pointers and testimony from the Ipperwash Inquiry.

The inquiry was established in 2003 and included the testimony of OPP personnel, Ontario government, Stoney Pointers, and members of the Kettle and Stony Point First Nation.

The chapter “Project Maple,” the code name the OPP gave its operation to keep containment of the Stoney Pointers who had set up in Ipperwash Park, focuses mostly on the testimony from the Ipperwash Inquiry.

The pages chillingly lay out the groundwork of the OPP and various departments in the Mike Harris’ government. It outlines decisions that were made to step up police action; information that was shared, not shared, ignored or not verified; help that was denied (including from then-Assembly of First Nation’s National Chief Ovide Mercredi); and the racist comments (some attributed to Premier Harris himself), stereotypes and beliefs that fueled the police/government action.

Perhaps most significantly, Ipperwash testimony indicated that with “Project Maple,” police only intended to arrest demonstrators who were not within park limits.

“There were no instructions about letting us—the ‘f-ing Indians’ and the ‘f-ers’ in the eyes of at least some of those giving the orders—know that we would only be asked to return to the park. No one thought to tell us that we would be safe—left alone—as long as we were inside the park. We remained ignorant of this important fact,” observed the Stoney Pointers.

Following the “Project Maple” chapter is the Stoney Pointers’ account of what transpired Sept. 5 and 6, 1995. It is chilling in a different way. Heartbreaking accounts of fear and not knowing and desperation to find out about family members—some younger than Simon—as the OPP crashed the site, used metal batons to beat down people, and discharged their firearms.

It was in that melee that Dudley George was fatally shot (pronounced dead at the hospital where he was driven by family members who were arrested upon their arrival) and when Bernard George was beaten severely.

“The worse thing I think about (is) how it was really scary,” Simon told Windspeaker.com.

But the story of Ipperwash Park starts well before September 1995 and that, says Simon, is what he wants non-Indigenous readers to understand when they read Our Long Struggle for Home.

“Hopefully (they get) a better understanding (of) what our people have gone through and continue to go through,” said Simon.

The 1827 Huron Tract Treaty created the Aazhoodena (Stoney Point) reserve in perpetuity. But in 1942, under the auspices of the War Measures Act, the federal government appropriated the land, turning it into the Ipperwash army training camp. Stoney Pointers were forced to relocate to the nearby Kettle Point reserve.

Stoney Pointers believed they would get their land back once World War II concluded. But that did not happen. What transpired was decades of writing letters, lawyers’ fees and petitions, but to no avail. Even a recommendation in 1992 from the Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs to have the land returned was unsuccessful.

Simon grew up next door to his grandfather Dan George. One of his dying wishes, says Simon, was to be buried at Aazhoodena When Dan George passed away in 1990, he was granted that wish.

“He was one of the first ones, I would consider, leading the journey back home,” said Simon.

Many people followed Dan George’s coffin to Aazhoodena, where he became the first person to be buried on the reserve since 1942.

“I had a dream about a week before (my grandfather) passed away… I dreamed that an eagle …was leading my grandfather’s procession,” said Simon.

On the day of the burial procession, a few people noticed an eagle in the sky.

“The eagle seemed as if he was at the head of the procession…It meant we’re going to get it back. (It means) we’re doing what we’re supposed to be doing, meant to do,” said Simon. “I still feel that way.”

Finally in May 1993, tired of waiting, Aazhoodena Elders led the way back to their land. With the hope that being at the army camp would move the process along, they proclaimed themselves as the interim government. They were joined by their children and grandchildren. Tents were pitched, trailers were brought on the land and, shortly after, the army vacated the premises. The barracks were then used for homes.

The success of that action encouraged the Stoney Pointers to go one more step and reclaim their beachfront land that had been turned into the Ipperwash Provincial Park. That move coincided with the end of the park season.

This was the backdrop to the police action of Sept. 6, 1995.

It has been 27 years since that night, but Simon said, “There’s a lot of emotion, I guess, what came up. Talking with my mother (Marcia Simon), she was helping with this book (and she) actually asked if she could step away from it because of the raw nature of the emotions that are still there.”

Those same feelings prevailed during the Ipperwash Inquiry.

“On one hand it was traumatic, but on the other hand it gave me a great deal of pride to be able to bring our story out into the light,” said Simon.

Our Long Struggle for Home: The Ipperwash Story will be launched at a community event at the Stoney Point reserve on Saturday afternoon.

Holding the launch in the community, said Simon, “is a very important step. It is the start of a conversation and a healing journey, to get more of the conversation with what ultimately needs to be done.”

Proceeds from the book, he says, will go into a fund to start an organization for Aazhoodena children to help them learn their language, culture and traditions.

The stories of the Stoney Pointers were pulled together for the novel by scholar and writer Heather Menzies. Our Long Struggle for Home: The Ipperwash Story is published by On Point UBC Press.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.