Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

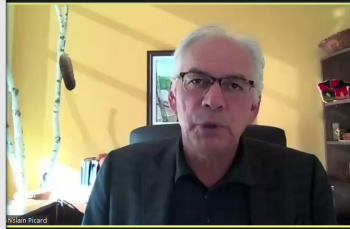

As Assembly of First Nation Quebec and Labrador Regional Chief Ghislain Picard hosted the seventh interactive roundtable on racism and discrimination, a coroner’s inquiry into the circumstances into the death of Joyce Echaquan continues.

Picard made the connection at yesterday’s roundtable that the AFNQL presented its action plan against racism and discrimination in the province one day after Echaquan died in Joliette hospital. The 37-year-old Atikamekw woman and mother of seven posted on Facebook the racist treatment she endured at the hands of health personnel just before she died Sept. 28, 2020.

“I think it’s very important for all of us to be mindful of that situation and certainly be reminded that these discussions are timely and much needed in this context,” said Picard.

Mistrust, he said, is creating tension between groups and that is obvious in the relationship First Nations people have with the judicial system and police services, which was the topic of the roundtable.

Picard pointed to the deaths last year of First Nations members Chantel Moore and Rodney Levi at the hands of police during wellness checks. He also drew attention to the brutal treatment of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam in Alberta by the RCMP during a stop for an expired license plate. He talked about the high rate of incarceration of Indigenous people, particularly Indigenous women. He called all of these “troubling facts.”

AFN British Columbia Regional Chief Terry Teegee, who is co-lead on the Justice portfolio with Picard, joined the other three guests on the panel discussion and pointed out that three women, all from the same First Nation community in BC, had been shot by the police. He said his own cousin in Prince George had recently been detained by the police and died.

“It speaks to the current state of affairs of many Indigenous peoples in this country,” said Teegee.

The relationship with the police, particularly the RCMP, has been long and not one built on trust, he said.

“It (is) a relationship where we’re seeing in today’s world that it is steeped in racism,” both in the treatment of Indigenous peoples and the attitude of the police, said Teegee.

“(It’s) a debate, I would say, is very polarized in Quebec, about how you name things. There’s always this fear to admit the existence, for instance, of systemic racism and its implications and its impacts,” said Picard.

He pointed out that the Quebec government has refused to say systemic racism exists, while Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante was “probably the first one to name systemic racism for what it is.”

Former Crown prosecutor Pierre Rousseau agreed with Picard.

“In Quebec the authorities, the politicians, are loath to recognize the evidence, because there’s lots of evidence of systemic racism. It needs to be said, to be expressed, to be acknowledged if we want to move forward,” said Rousseau.

“It’s vital that we acknowledge that racism and discrimination is baked into our criminal justice system. It’s baked into the history of policing with Indigenous people today,” said Jonathan Rudin, lawyer at Aboriginal Legal Services in Toronto.

“We also need to acknowledge … that systemic discrimination and systemic racism is at the root of the involvement of Indigenous peoples with the justice system.”

Carlo DeAngelis, Indigenous liaison officer with the Montreal Police Service, came under fire when he said many Indigenous people were re-arrested because they kept breaking release conditions.

“Some of the conditions are just stupid and they shouldn’t be imposed and this is part of the problem,” said Rudin. “We can’t keep putting the blame on Indigenous people for not doing what they shouldn’t be asked not to do … That speaks to the systemic nature of the problem.”

The starting point of the issue, he said, is colonialism.

“If the problem is the colonial system then there’s limits to have the colonial system solve the problem it creates,” Rudin continued.

Rousseau agreed that the system needed to be decolonized.

“There is no magic in the legal system. It is profoundly cultural. We have a mainstream system here that was imposed on Indigenous people without any consultation, without any agreement. We are seeing the failure of the system,” he said.

Rousseau said Indigenous legal traditions need to be recognized.

“I don’t understand why we’re so loath in Canada to accept legal pluralism … to have different justice systems that run parallel to each other,” he said.

DeAngelis said while change has been a “bumpy road” there is “real will” in the Montreal Police Service to see change.

He said the Indigenous community needed to have the right to govern their communities and police needed to collaborate with them.

“Going forward (it) is (about) dialogue and respect of each other,” said DeAngelis.

“Respect,” said Picard, “is a key word.”

The round tables, held in both French and English, are part of the AFNQL’s Action Plan on Racism and Discrimination towards First Nations. The objective is to stimulate discussion and mobilize both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations around the issues.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.