Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Northwest Coast artist Luke Parnell views his creative process as a form of storytelling. While studying carving as a youth, Parnell, born in Prince Rupert, B.C. in 1971, says his only references to artists working in the Northwest Coast style was the celebrated output from artists Robert Davidson and Bill Reid.

As a youth, Parnell was naturally drawn to creating art and had been greatly inspired by comic books like X-Men, and to a lesser extent, characters like Batman.

When he first saw an early National Film Board documentary on Bill Reid Parnell was perplexed by Reid’s claim that he didn’t feel that the Northwest Coast style “could go much further than what it is now.”

“You know, I don’t try and expand the boundaries of the artwork. I just do what I want to do, and I see it as part of the storytelling tradition,” Parnell explained over the phone from his home in Toronto.

Parnell is Wilp (house) Laxgiik (eagle clan) Nisga’a from Gingolx on his mother’s side and Haida from Massett, Haida Gwaii on his father’s side. He originally mentored with master Tsimshian carver Henry Green for three years before traveling to Toronto in his early twenties to acquire a Bachelor’s degree from the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD). He then returned to the west coast for a few years to work on a Master’s degree from the Emily Carr University of Art and Design.

Today he is a well-established multidisciplinary artist who teaches at OCAD and has exhibited his work at galleries such as the MacLaren Art Centre, the National Gallery of Canada, the Biennial of Contemporary Native Art in Montreal, and the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Parnell has also served as artist in residence at the International Cervantino Festival and the Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity.

A new solo exhibition of Parnell’s work called Indigenous History in Colour will begin its run at Vancouver’s Bill Reid Gallery on Feb. 3 and will continue until May 9 with an opening online ceremony to be hosted by the gallery on Feb. 2.

The exhibition, which first premiered at MKG127 Gallery in Toronto back in July 2020, will mark Parnell’s first exhibition at the Vancouver gallery. It will present several of the artist’s works created in the last few years and will feature creations in a number of disciplines that transcend his traditional work as a carver.

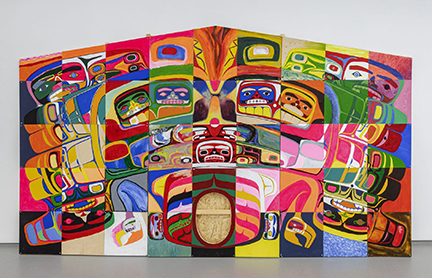

Of the many pieces included, the exhibition will feature a new collaborative work called Neon Reconciliation Explosion, which Parnell originally conducted as an experiment during the 2018 Home Away Home contemporary art festival in Toronto.

Deeply disenchanted with the concept of “reconciliation” after the murder trials of non-Indigenous men accused in the killings of Indigenous Sagkeeng teenager Tina Fontaine and 22-year-old Cree man Colten Boushie when both ended in acquittals, Parnell devised the project as a way of conducting community “research.”

“I was really just exploring. It was like research in a sense. I didn’t really understand the concept of ‘reconciliation’ myself and that was the purpose of the artwork. I, myself, was trying to come to terms with it, and so I asked (the participants) to be honest about what they were doing, and I left the last panel for myself,” Parnell explained.

Neon Reconciliation Explosion is an expansive piece where Parnell drew a large pattern on 44 16 inch by 16 inch panels that he distributed to 55 community members attending the event. They were asked to create something on each panel that would represent what “reconciliation” meant to them. The central panel was completed by Parnell himself after all the other panels had been painted by the other participants.

“I really struggled with it because I didn’t want people to feel like I was gaslighting them or that I had some kind of ulterior motive all along,” Parnell said. “But I also had to be honest with what “reconciliation” meant to me, and that’s why I finished the piece the way I did.”

Many of the works included in his upcoming Indigenous History in Colour exhibition demonstrate the artist’s interest in working in disciplines outside of his original practice as a carver, and explores Parnell’s passion and willingness to blend traditional images and methods with contemporary images and methods.

Included in the exhibit is a large print of a digital artwork he originally created for his Instagram account called Bear Mother, a piece of work that was not originally intended to be presented in a gallery environment.

“Before I did Bear Mother I didn't really work with colour. I was mostly working with just black and red. And so the Bear Mother piece was actually a way for me to learn more about working with colour,” Parnell explained.

To create Bear Mother Parnell used the Procreate App on his IPad, which allowed him to easily experiment with colour without a massive investment in time, and it’s something that he’s excited to keep working with on future projects.

“Because I come from a carving tradition it's very high stakes and once you start a carving you just have to follow the plan that you create until you're done with it,” Parnell explained. “Once you’ve designed a piece there’s not a lot of creativity left in the process until you have finished and move on to the next piece. I've always been searching for something where I could just be creative very quickly and then be done with it in a couple of days rather than in a couple of weeks. So I love it.”

Another interesting work included in the Bill Reid exhibit will be Parnell’s first exploration into filmmaking. Dedicated to the idea that the creative process is the true essence of his practice, Parnell feels that it is the process that creates the story, which in turn enriches the cultural reservoir.

In 1959 Bill Reid was the subject of a documentary where he led an expedition to ‘salvage’ historic totem poles from a deserted village in Haida Gwaii. In a response Parnell worked with a small team of filmmakers on the film Remediation, which depicts his journey from Toronto to Haida Gwaii.

Parnell says he came to filmmaking because he “realized that if you have a story that needs to be told then you have to find the right medium to tell the story…and so that’s how I started to work in other media.”

Quiet and meditative and completely free of narration Remediation depicts Parnell carrying a section of one of his own totem poles on his back throughout the journey, which culminates with the artist sacrificing the carving over a fire on an isolated Haida Gwaii beach.

“I watched the Bill Reid film from the 1950s and I felt it just sounded so condescending, and I just thought that I wanted to do a reaction to this film. So, I realized that if I was going to create a reaction to the film I had to, in turn, make a film myself.”

Ultimately, as with much of his work, Parnell viewed the process of making Remediation and the sacrifice of his carved pole as the actual work of art itself, rather than the carving existing as the main art form.

Luke Parnell’s solo exhibit Indigenous History in Colour premieres Feb. 3 at the Bill Reid Gallery in downtown Vancouver. To attend the online opening of the show on Feb. 2 you can follow the link posted today on the gallery’s website www.billreidgallery.ca

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.