Canada Post unveiled today four new stamps that encourage awareness and reflection on the legacy of Indian residential schools and the need for healing and reconciliation. The stamps will be released Sept. 29 in connection with the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on Sept. 30. They are the first in an annual series showcasing the visions of First Nations, Inuit and Métis artists for the future of truth and reconciliation.

Between the 1830s and 1990s, more than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children across Canada were taken from their families and sent to federally-created Indian residential schools. They were stripped of their languages, cultures and traditions.

Children endured unsafe conditions, disease, and physical, sexual and emotional abuse while at the church-run schools. Thousands of them never made it home,reads a press release.

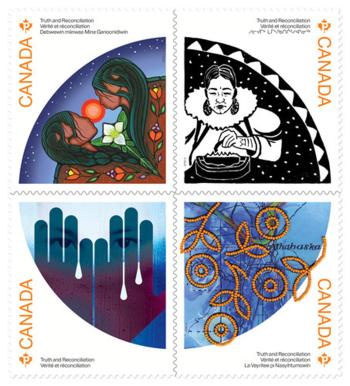

Jackie Traverse, an Anishinaabe, Ojibwe artist, said her image represents the seeds of change.

“Here we have man and woman, the Elders, their children and their grandchildren. I've put the (unofficial) national flower, the bunchberry, in the centre to represent Canada, with the roots from the seeds reaching to the past. For all of us to experience a good harvest we need to share the sun, water and the land. This is how we bring forth good crops and ensure everyone has the harvest of tomorrow."

Traverse's mother died at a young age and her siblings were apprehended in the Sixties Scoop. She grew up in one of Winnipeg's toughest neighbourhoods.

Traverse is a multi-disciplined Indigenous artist who works in several media, from oil and acrylic paintings to mixed media, stop-motion animation and sculpture. She draws inspiration from her Indigenous culture and her experiences as an Indigenous woman living in Winnipeg. Her work speaks to the realities of being an Indigenous woman.

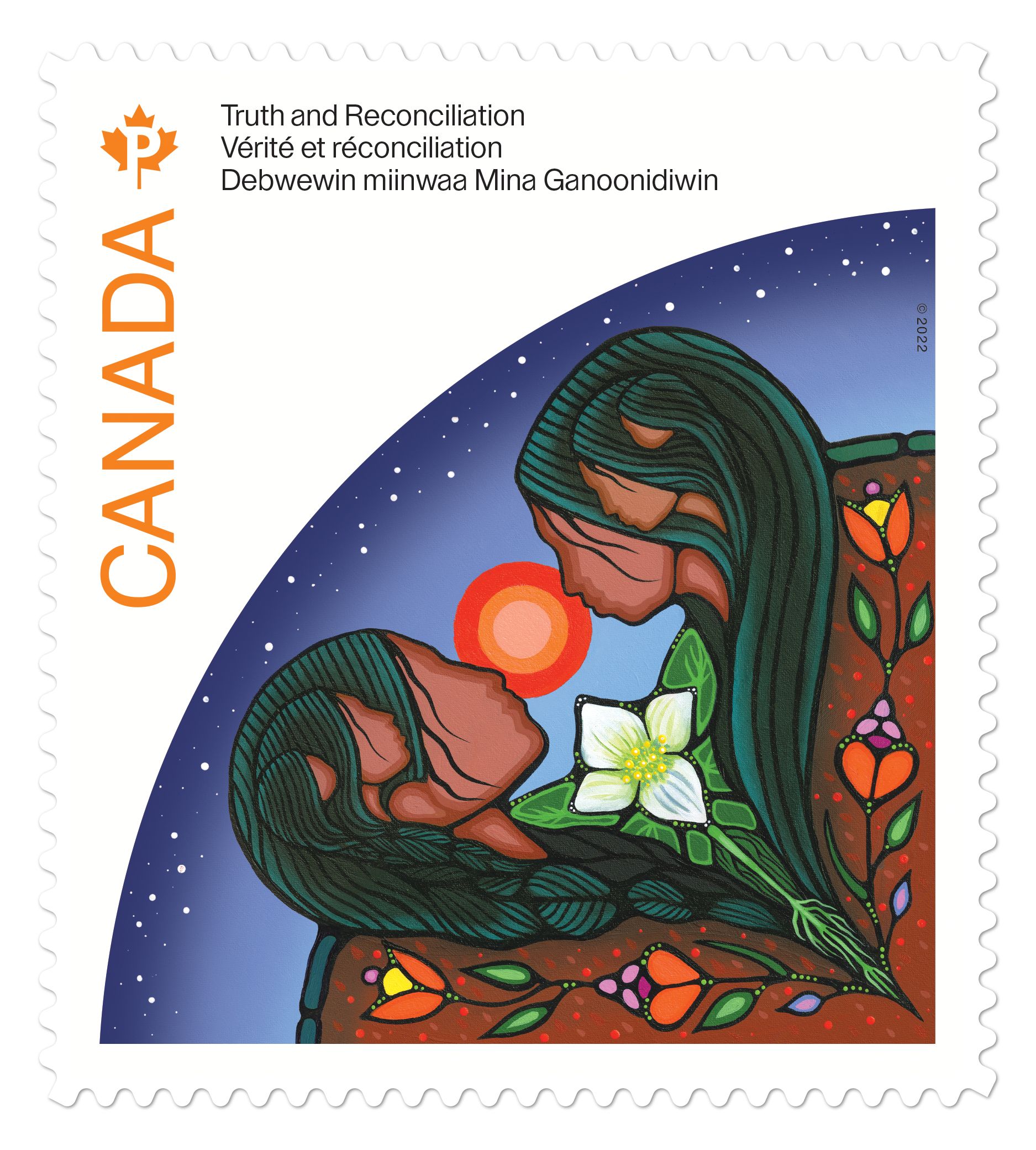

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, an Inuit artist from Qamani'tuaq (Baker Lake), Nunavut, said she believes each group within Canada has a different responsibility for reconciliation.

"For Indigenous people, our responsibility is to ourselves and to others within our communities: learning or passing on our language and culture that was attacked only one generation ago.

She said she created a woman lighting a qulliq, the traditional Inuit stone lamp used for heat and light to signify caretaking.

“This woman is carrying on in her culture as she has always done, taking care of herself and others and healing."

Kabloona comes from a family of renowned Inuit artists. Art is how she connects with others within her culture, showcases her Inuit heritage, and expresses her Indigenous identity. Kabloona's work puts a modern take on traditional Inuit imagery, and strong women frequently make appearances in her art.

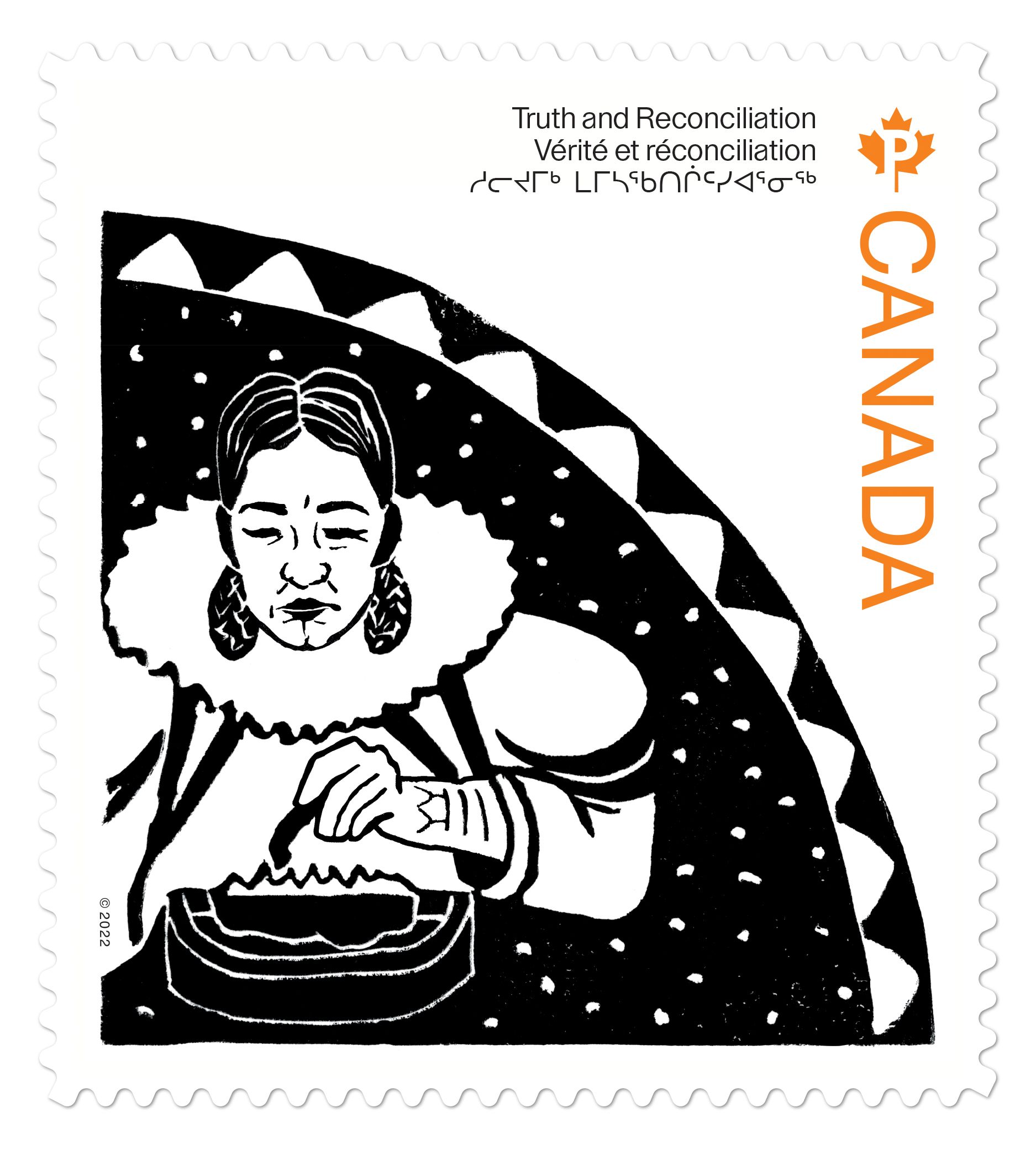

Kim Gullion Stewart, Métis artist from Athabasca, Alta., who currently lives in Pinantan Lake, B.C. said flowers in Métis art remind people to live in a symbiotic with with the land. Waterways and one another.

“In this piece I have placed beaded flowers on top of contour lines representing the Rocky Mountains, twisty lines for rivers and dashes demarking political territories. While maps like this one are a two-dimensional record of historical process and places, they are incomplete until they include elements that are important to the people who are Indigenous on this continent."

Gullion Stewart’s father connects her to the Métis homeland of Red River, Man. She creates metaphorical meaning by connecting Métis cultural art forms (hide tanning, beading, quillwork) with contemporary and graphic art forms. In her art, she searches to uncover the depths of her Métis identity and learn Métis knowledge systems that have been hidden, lost or adapted as a survival mechanism.

Blair Thomson, is an artist and graphic designer. His stamp depicts A pair of hands held over the eyes and human face.

“Intended to be cross-representative — those of Indigenous peoples/survivors, covering their face in sadness, pain, memories, and those of the settler, masking their view of reality and shame. Tears stream from between the fingers. The background further connects to the school windows, looking out and dreaming of home. The eyes looking out from behind the hands reinforce the message that settlers must never look away again.'"

Thomson is founder and creative director of Believe in, a design practice with studios in Canada and the United Kingdom. His work is multi-award winning and has been featured in many leading design publications worldwide. Thomson is the collector, archivist and historian responsible for Canada Modern (an archive of modernist, Canadian graphic design from 1960-85).

Stamps and collectibles are available at canadapost.ca and postal outlets across Canada.