Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

The boy from Buzwah grew up to have a doctorate attached to his name.

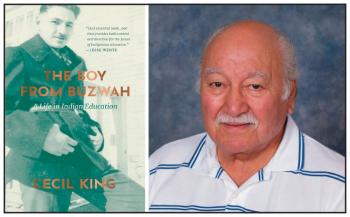

And whether he’s still that boy from Buzwah, situated on Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve on Manitoulin Island, Ont., or the man who is Professor Emeritus of Queen’s University, “that’s a matter of opinion,” said Dr. Cecil King, now 90 years old.

King’s memoir, The Boy from Buzwah: A Life in Indian Education, will come out later this month.

The memoir traces King’s “long and … arduous … happy (educational) trail” starting at the small Buzwah Indian Day School through to Garnier Residential School run by the Jesuits in Spanish, Ont. to training as a teacher in Toronto and eventually earning degrees.

Through it all, King held on to and thrived in his Ojibwe language.

Blessed with four qualified First Nations teachers at Buzwah Indian Day School who “stuck closely” to the curriculum set out by the Ontario Department of Education, they were also “very Anishnabe,” wrote King and “were, in fact, role models that it was possible to teach in the English world and still be Anishnabe.”

His experience at Garnier Residential School ran contrary to much of what has been reported about Indian residential school abuse. Although it held true that students were forbidden to speak Ojibwe in front of the Jesuits, King still spoke and learned more of his language with other students in the basement of the residential school.

“We created a culture within the institution’s culture. We found a way to circumvent the forces that dominated,” he wrote.

After graduating Garnier as valedictorian in 1953, King would go on to be influential in Indigenous education. He became a warrior for the 1973 goal of Indian control of Indian education and the right to self-determination, including placing Indigenous languages, cultures, histories and values into curricula in training institutions, which he helped create.

Over his career, he founded the Indian Teacher Education Program, became the first director of the Aboriginal Teacher Education Program at Queen’s University, and developed Ojibwe language courses across North America.

What he has accomplished in his 60-plus year career, he said, “is a very difficult question… Languages change and so does the time with languages.”

King is also humble when it comes to talking about the impact his life’s work has had on other champions of Indigenous language and education.

“I don’t think they are inspired. I think basically they pick up parts of all this newness seeping into the milieu of talking,” he said.

King challenges readers of his book to carry on his work.

“Don’t try and teach the Native language as a piece of artifact. It’s here now. Why not include it in what you’re doing? Or include parts of that. It does belong as a language and that’s the point,” he said.

“Because my dad is an Elder now, the importance of language is so near and dear to his heart as it was when he was a young boy in Buzwah first learning and going to school,” said Alanis King, Cecil King’s daughter.

Alanis joined her father on his recent telephone interview with Windspeaker.com.

“It seems to me like it’s been a full circle where really the ultimate importance of education is knowing who you are and inside of that is knowing your language. And if you have a relationship to your original language, that’s going to complete and inform yourself and your being and how you carry on in mainstream in society,” she said.

Alanis shares that passion for language with her father. In his memoir, Cecil writes of his second-born daughter, “She has the gift of telling a story in a gentle way so that the audience realizes the hard realities of Indigenous lives in Canada without feeling hatred or rancour.”

Alanis is a playwright and director. She writes about Anishnaabec people, their history and their heroes. She wants to inspire Indigenous young people so they can learn about themselves from sources that aren’t only mainstream. Her language is a big part of her plays.

“(Ojibwe) is so creative. There’s so much humour. There’s so much good medicine inside our language and it gives me a real sense of worth, fascination that I can continue until the day I leave this world. There’s so much to learn how our worldview is so unique, special and inspiring,” she said.

Cecil translated Alanis’ play Gegwa, which the Centre for Indigenous Theatre in Toronto performed and toured in 2007. Even though some of the actors weren’t Anishnabe, they rose to the challenge of performing in the language, says Alanis.

“I really felt like those could become our classics,” she added.

Her father has always advocated for Indigenous languages, she said.

“So now, I don’t find it surprising at all that now it comes down to language being the ultimate education for self-confidence, for self-worth, for all of those things. I think that’s what he’s attaching to all of his answers here today,” said Alanis.

Cecil King is a recipient of Queen Elizabeth’s Golden Jubilee Medal, the Saskatchewan Centennial Medal, and the National Aboriginal Achievement Award for Education. He currently resides in Saskatoon.

The Boy from Buzwah: A Life in Indian Education is published by the University of Regina Press. It will be launched virtually with McNally’s Saskatoon on Feb. 22.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.