Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

As the Manitoba Metis Federation (MMF) looks to form a new government, it’s not giving up on an old battle.

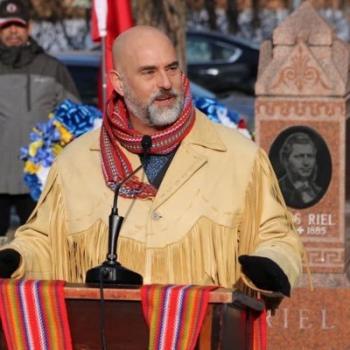

“There are people who want to remain true to the Métis Nation, remain true to the definition, outside of our provincial borders. So the MMF now is asserting its responsibility to represent these people who are feeling left out in the cold, who are feeling that the Alberta, Saskatchewan presidents are selling the heart and soul of the Métis Nation for a little bit of expediency,” said Will Goodon, minister of housing for MMF.

“But at the end of the day, the MNO (Métis Nation of Ontario) is the issue.”

This past September, the MMF, one of the founding members of the Métis National Council (MNC), left that organization following the years-long battle with the MNO over the implementation of the MNC’s definition of Métis. That definition, accepted in 2002, reads “a person who self-identifies as Métis, is of historic Métis Nation Ancestry, is distinct from other Aboriginal Peoples and is accepted by the Métis Nation.”

At the heart of the dispute was the MNO’s decision to include Métis communities they said were historic but which the MMF claimed were not. The MNO’s stand was backed by the Métis Nation of Alberta (MNA) and Métis Nation-Saskatchewan (MN-S), the two other founding members of the MNC.

Research undertaken by the MMF and released this past February disputed a joint statement from the MNO and the Ontario government in 2017 that said there were seven historic Métis communities in that province. According to the MMF, Rainy River/Lake of the Woods is the only historic Métis community in Ontario that is part of the Métis homeland.

However, in September at the MNC general assembly, a panel with representatives from the MNO, MN-S, MNA and Métis Nation British Columbia and experts was struck to gather information. That panel will present findings to the MNC that will include reviewing “the history of the seven Ontario communities through the lens of the national definition and contemporary Métis governance.” The panel is to report recommendations within 12 months from the initial meeting.

As far as Goodon is concerned, the MNO can’t offer any information that will back up their claim.

“We are definitely very concerned about protecting the Métis Nation. I don’t think our ancestors would want us just to lay down our arms and give in and say, ‘Let everybody in.’ That would be an affront to all our ancestors who fought in the Red River resistance, the Northwest resistance and then continuing on through modern day,” said Goodon.

Funding from the federal government is funneled through the MNC, which then divides it based on a formula that sees the three founding Métis members each receiving 25 per cent and then British Columbia and Ontario splitting the remaining 25 per cent equally.

Goodon says discussions are ongoing now that will see funding come directly to the MMF and he anticipates the 25 per cent figure “will be just the basement.”

The MMF signed a self-government agreement with Canada this past July that mandates it to represent the Red River Métis “no matter where they live,” says Goodon.

“To make it fairly simple, the Métis Nation and Red River Métis are practically one and the same,” he said.

Goodon adds that there are at least 2,000 Métis outside of Manitoba who have “signed up” to be represented by MMF. He also says communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan have reached out.

At this point, he says, there is no move by MMF to ask Métis outside of Manitoba to rescind their memberships with any other Métis Nation in order to be represented by MMF. He notes that some services, such as housing, health and education, need to be funded through the local association.

Goodon sees the provincial boundaries as artificial.

“Why is the Métis Nation so stuck on these straight lines that cut right through our homeland? They’re really a colonial construct. We’re really asserting our sovereignty, our identity as a nation. We’re looking beyond being forced into a box by these colonial structures,” he said.

The MMF has yet to determine what its new government will look like.

“There’s going to be consultation processes that are going to happen across the homeland. So folks who are in Île-à-la-Crosse (Saskatchewan) or Lac La Biche (Alberta) or in the United States or in the Northwest Territories, wherever Red River Métis people are that’s where we want to talk to these folks and then get a good understanding of what their priorities are,” said Goodon.

In 2018 the MNC adopted a map of the Métis homeland that set out its borders. Goodon says this map would “more than likely” form the basis of the MMF homeland but “may need a little more tweaking.” That tweaking won’t be on the eastern boundaries but will focus on the other boundaries.

Even in the west, says Goodon, there are discussions to be had where the Blackfoot assert there were no Métis in southern Alberta.

“I’m not saying we’re going to agree with them, but at the same time we should be talking to them in the same way we’re talking to other Indigenous Nations,” said Goodon.

Former MNC president Clement Chartier has been appointed by MMF President David Chartrand as ambassador for the federation in both international and inter-nation issues. Chartier’s work will include negotiating accords, already underway, with the Algonquin Nation and Mi’kmaq.

“They’re facing this identity theft. We’re facing this identity theft. In order for us to have a little more clarification, I think it’s really upon us to cooperate with legitimate nations and that’s what we’re trying to do,” said Goodon.

He says the MMF will be having further discussions with the Alberta Métis Federation. The two federations signed an MOU in July.

“We agreed to work together to protect the nation and I definitely think they’re going to be part of the conversation absolutely,” he said.

At this point, Goodon expects consultation to take place in urban centres, including Saskatoon, Edmonton and Yellowknife. However, he says web-meetings and discussions are also possible.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.