Summary

Windspeaker.com Contributor

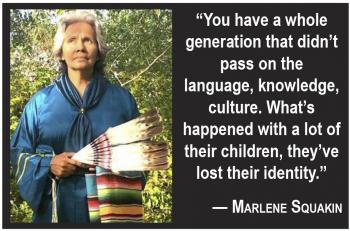

There can be real power in the Indigenous Languages Act, introduced Tuesday in the House of Commons, if the funding that comes with it “trickles down” to the grassroots, said Indigenous language instructor Marlene Squakin.

Squakin was one of many people to take to Facebook to laud the bill, as in her case, or dismiss it as a waste of money.

For those people, who like Manfred Tobin, wrote, “… you wouldn’t want to have to teach your own kids your language at home,” Squakin says people don’t realize that many Indigenous people lost their languages through residential schools. They also don’t realize that as the Elders pass away the languages pass away.

For those people, who like Patricia LeDoux, wrote, “I think there’s more pressing issues that Perry Bellegarde has to address,” Squakin agrees. Housing and clean water are concerns, but she also says learning the language will help ground young people, giving them pride and dignity.

“You have a whole generation that didn’t pass on the language, knowledge, culture. What’s happened with a lot of their children, they’ve lost their identity. You see a lot of people, the adverse effect it had on them… Some of our young people, they were involved in alcohol and drugs and once they started finding out about their language and their culture and their ceremonies and songs, it became a complete turn-around for them.

“You see the effects it’s had on them since they regained their identity,” said Squakin, who has been the Okanagan language presenter for the Central Okanagan Public Schools for the past number of years. She’s presently on leave from her position.

In announcing Bill C-91, the Indigenous Languages Act, alongside Heritage and Multiculturalism Minister Pablo Rodriguez, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde called it “landmark legislation to protect and strengthen Indigenous languages.”

In earlier remarks, Bellegarde focused on the need for “sufficient, sustainable and long-term funding … (for) schools on-reserve, as well as in urban and rural settings to create and implement effective bilingual and immersion education programs beginning with pre-school age children.”

Squakin agrees there’s a role that schools play in reviving Indigenous languages, but she says it has to go beyond schools.

As a language instructor in the public school system, Squakin finds herself teaching her Okanagan language to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students from Kindergarten to Grade 7. With about 20,000 students in the district, about 2,000 are First Nations and about 250 to 400 are from the Okanagan Indian Band.

“It created cultural awareness and it was really effective with dealing with stereotypes, from the students, teachers, principals, all the way up to the board. I call it creating space and creating awareness and giving a positive viewpoint to our people,” she said.

Squakin notes it’s difficult to get Indigenous language into the classroom in the public school system. For band-run schools, it can be a part of the curriculum.

However, Indigenous languages curriculum is still being developed and it’s a costly, time-consuming endeavour; one reason why Squakin says money promised through the act must make it to the people on the ground.

“Hopefully the funding will trickle down all the way to the communities that need it. I say trickle down because that trickle-down effect usually never ever reaches the community level. It gets lost up in the administration level cycle,” she said.

Squakin wants the funding to go to language centres or language associations, as well as into the classroom.

While Bellegarde and Clara Morin Dal Col of the Métis National Council are pleased with Bill C-91, two Inuit organizations have expressed their displeasure that the Bill does not specifically protect Inuktut.

In late 2017, the Inuit Tapiriit Kantami released a paper on the national Inuit positions on the federal Indigenous languages bill stating that “the Government of Canada should consider the possibility of standalone Inuktut legislation in the formation of distinctions-based legislative content.” The paper was provided to the federal government.

However, Bill C-91 makes no such distinction, although its preamble does state “First Nations, the Inuit and the Métis Nation have their own collective identities, cultures and ways of life” and “the status of Indigenous languages varies from one language to another.”

That’s not good enough, say ITK president Natan Obed and Aluki Kotierk, the president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.

“The absence of any Inuit-specific content suggests this bill is yet another legislative initiative developed behind closed doors by a colonial system and then imposed on Inuit,” said Obed in a statement.

“Notwithstanding all the rhetoric about ‘co-development’, this bill shows no measurable Inuit input, despite our best efforts to engage as partners,” said Kotierk in a statement.

A news release issued by Canadian Heritage calls the bill “a collaborative approach … adopted with Indigenous Peoples,” which included “intensive and collaborative sessions” over two years.

The centrepiece of the bill is the creation of a federal commissioner of Indigenous languages. It also calls for the minister to “consult with diverse Indigenous governments and other Indigenous governing bodies and diverse Indigenous organizations in order to meet the objective of providing adequate, sustainable and long-term funding for the reclamation, revitalization, maintenance and strengthening of Indigenous languages.”

In the 2017 budget, the Liberals committed $89.9 million over three years for Indigenous languages.

Canadian Heritage said it will continue to work with AFN, ITK and MNC “in the coming months through the next stages of the legislative process.”

Figures offered by Canadian Heritage say in 2016 15.6 per cent of Indigenous people could speak their mother tongue, down from 21 per cent in 2006. Also in 2016, 12.5 per cent of Indigenous people declared an Indigenous language as their mother tongue compared to 14.5 per cent five years earlier.