Summary

Windspeaker.com Contributor

EDMONTON

Nadine Callihoo had barely started her workshop on dealing with police when she was hearing a story that was all too familiar.

Sally (not her real name), a young Indigenous woman who lives in the Abbottsfield neighbourhood in east Edmonton, said she was not taken seriously by the Edmonton Police Service when she reported she had been gang-raped.

“The police did not take me seriously. I was victim-blamed and I was victim-shamed,” said Sally, adding the police insinuated she was hanging around with the wrong crowd, although the situation that led to the sexual violence was a matter of convenience for the gang.

“I hear (Sally’s) story every time. Unfortunately, even as victims, our police protection services are failing in that sense as well,” said Callihoo.

For the past 13 years, Callihoo has been delivering a variety of legal-themed workshops for the Native Counselling Services of Alberta across the province.

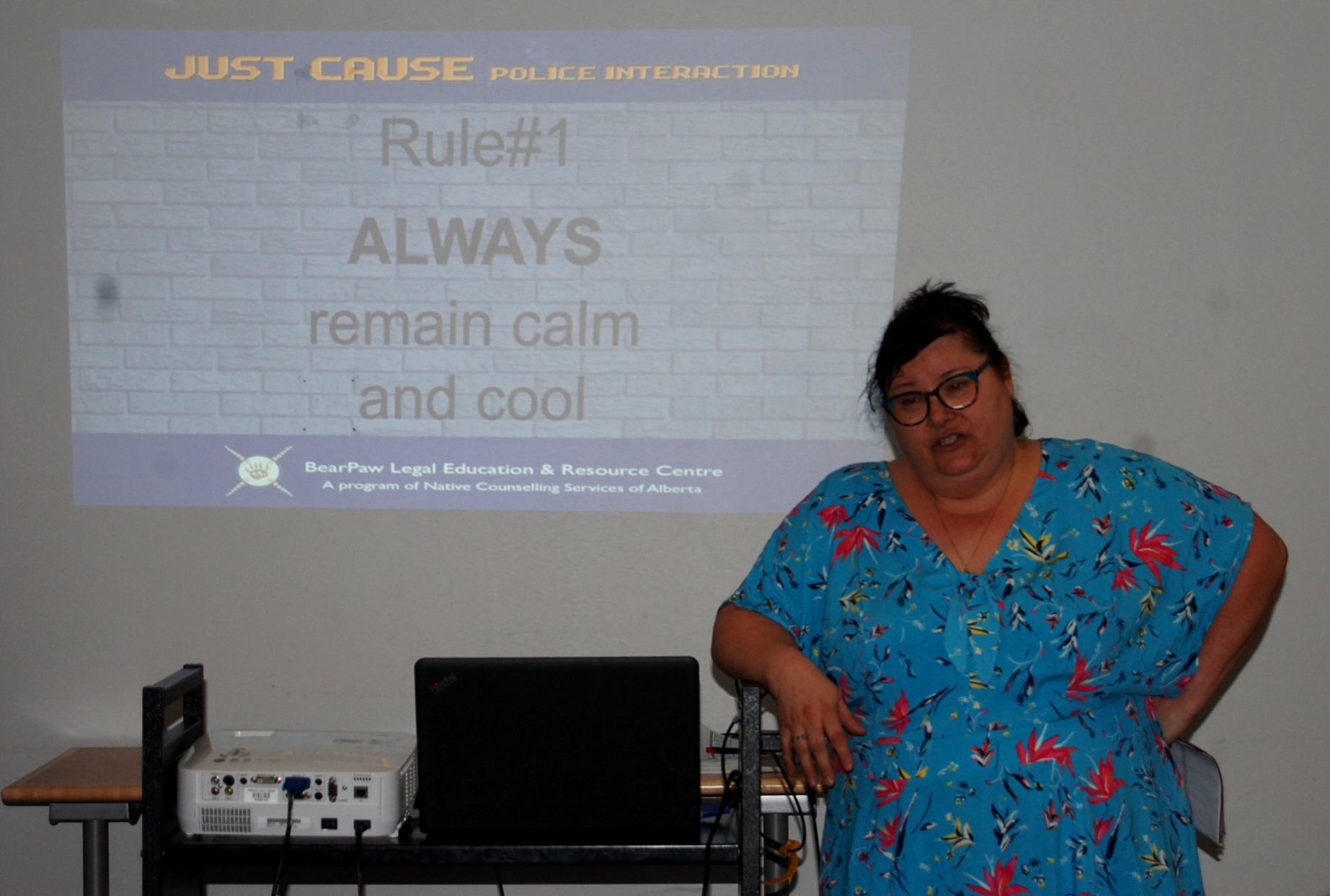

This workshop, entitled Just Cause, was delivered to a handful of participants at the downtown branch of the Edmonton Public Library on Oct. 3.

Part of that workshop included how to launch an official complaint against the police.

“Don’t be afraid to report misconduct,” said Callihoo, even though such conduct is initially reported to the police officer’s direct supervisor.

“We, the people, are saying this is not a good system, because how can the police investigate themselves? Can they be objective? Maybe, maybe not,” she said. “I suspect sometime in the next few years there’s going to be a shift.”

The police are legally obligated to investigate every complaint and the complainant has the right to know the outcome of the investigation, said Callihoo. If unhappy with the findings, the decision can be appealed. The appeal goes to K-Division, also a branch of the RCMP.

However, there is an external avenue for complaints against the RCMP and that is the Commission for Public Complaints, pointed out Callihoo. Although CPC only has jurisdiction over the RCMP, she said they will provide guidance for those who have complaints against the Edmonton or Calgary police services.

To give power to a complaint, Callihoo said it is vital to be a “good witness for yourself.”

Write down the details, collect statements from witnesses, take photographs of bruises, and if medical attention is required, get hospital or medical records.

She also said to use a cell phone to record the incident as it is occurring, but be sure to let the police know this is being done. If the police aren’t notified, she said, the recording cannot be used in court.

“If the police try to tell you, ‘No, you can’t (record),’ tell them, ‘The Supreme Court of Canada says that I can.’ If they tell you that they want to take your phone away, tell them, ‘The Supreme Court of Canada says it’s my right to do this and you can’t take it,’” said Callihoo.

The only way the police can take away a cell phone is if it is used in the commission of a crime, she said.

Callihoo’s presentation also included basic steps for dealing with the police, starting with the advice to remain calm.

“When I tell people ‘when you lose your temper, you’re giving away your power’, people see it in that way, and it’s, ‘Ooh, I don’t want to do that’,” she said.

Attitude is also important, she said.

“I always really try to stress there’s this very fine invisible line between asserting your rights and just being an (idiot) about it. You don’t want to be aggressive, but please assert your rights,” she said.

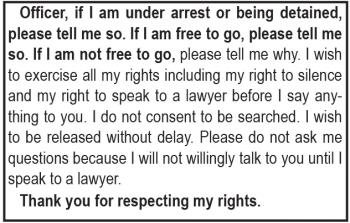

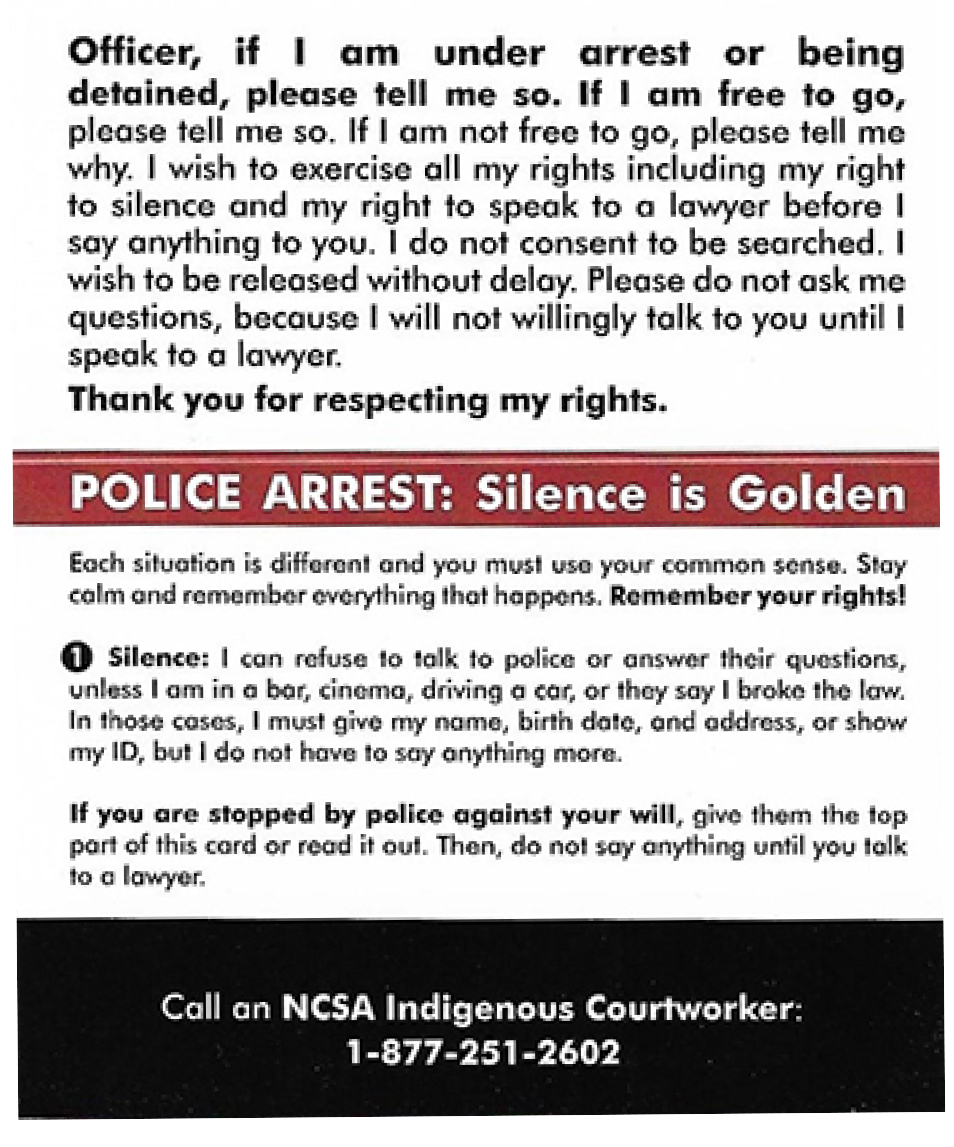

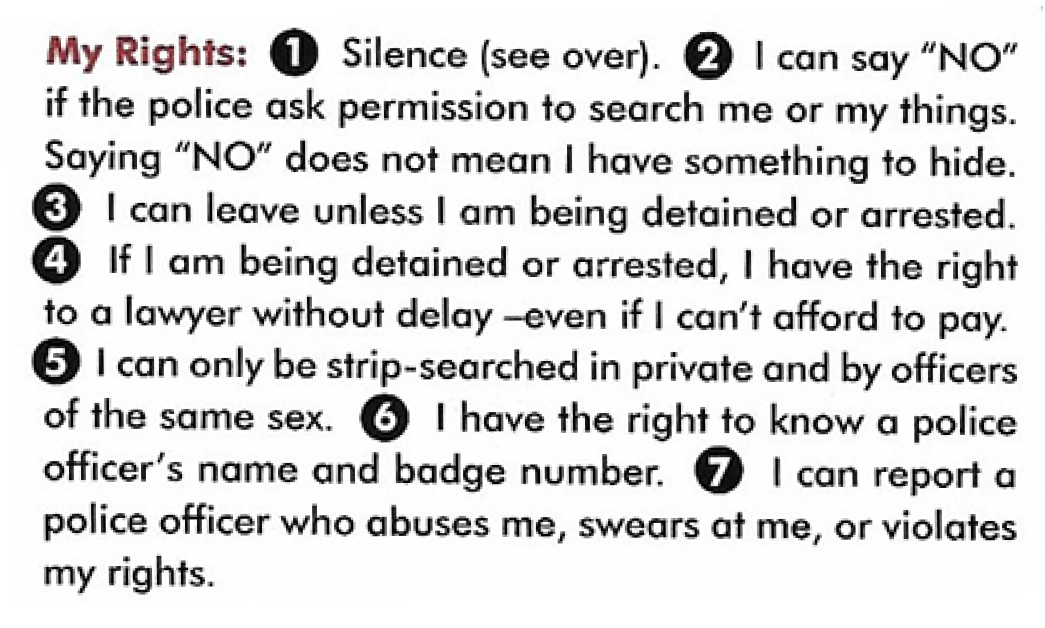

Callihoo distributed Statement for Police cards, which outline seven basic rights, including the right to remain silent, the right to refuse searches, the right to leave if not arrested, and the right to a lawyer.

In northern Alberta, she said the RCMP embrace the Statement for Police cards.

“They will hand out the cards themselves because they find that informed clients are less defensive, easy to work with … if (they) aren’t scared or intimidated,” she said.

Callihoo’s workshops are funded by the Alberta Law Foundation. While the material has been created specifically for Indigenous people, workshops offered in the cities have attracted other racialized Canadians who have had poor interactions with the police.

Police attitudes are starting to change, said Callihoo, although the amount of change “varies from region to region.”

“I’m not naive enough to believe that every police officer has done a 180 (degree turn). I think there’s still issues. Obviously, there are still issues. There is still ignorance out there,” she said.

If the level of police incidents have decreased, Callihoo said it has more to do with the understanding that has come through education.

“Indigenous people have found their voices. They’re accessing resources more, they’re learning what their rights are and they’re asserting themselves more. But also because on the flip side of that, I also believe more and more non-Indigenous people are learning more about the historical trauma, residential schools, Sixties Scoop, the Indian Act, all of that stuff through the generations Indigenous people have had to endure. There’s a better understanding on that side, too,” she said.

Callihoo stressed that the workshops are not to be seen as anti-police.

“I don’t want to come across as I’m trying to slam the police. They have a tough job to do, they really do, but you’re going to find some bad apples in every profession, and it’s up to us to protect ourselves,” she said.