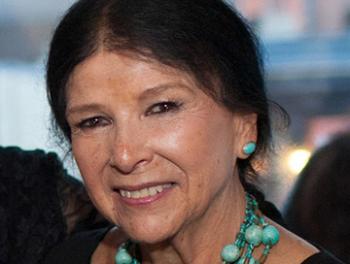

Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin was surprised when she heard the news that she’d been named the recipient of the 2020 Glenn Gould Prize honouring her life’s work.

While she’d become aware earlier this year that she had been nominated for the award, she admitted she didn’t give much thought to the possibility of winning.

“There’s no way I would ever think that I would receive such an honour. It was very moving for me,” she said.

The biannual prize, named for the celebrated Canadian classical pianist Glenn Gould, includes a $100,000 award and a bronze sculpture of Gould by Canadian artist Ruth Abernethy.

Obomsawin said she was working on a new film project in her Abenaki community of Odanak in Quebec when she received the phone call, and that made the experience extra special.

Obomsawin, a member of the Order of Canada and holder of honorary degrees from multiple universities across Canada, has produced more than 50 documentaries and films about Indigenous culture and issues. Among the most notable are Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance and Incident at Restigouche. She’s also had an extensive career in both music and visual arts and has worked in a variety of roles with the National Film Board since 1967.

This year, Obomsawin said she’s been happy with the time spent during the pandemic looking through personal past film archives, and has been fortunate to stay healthy and working on upcoming projects.

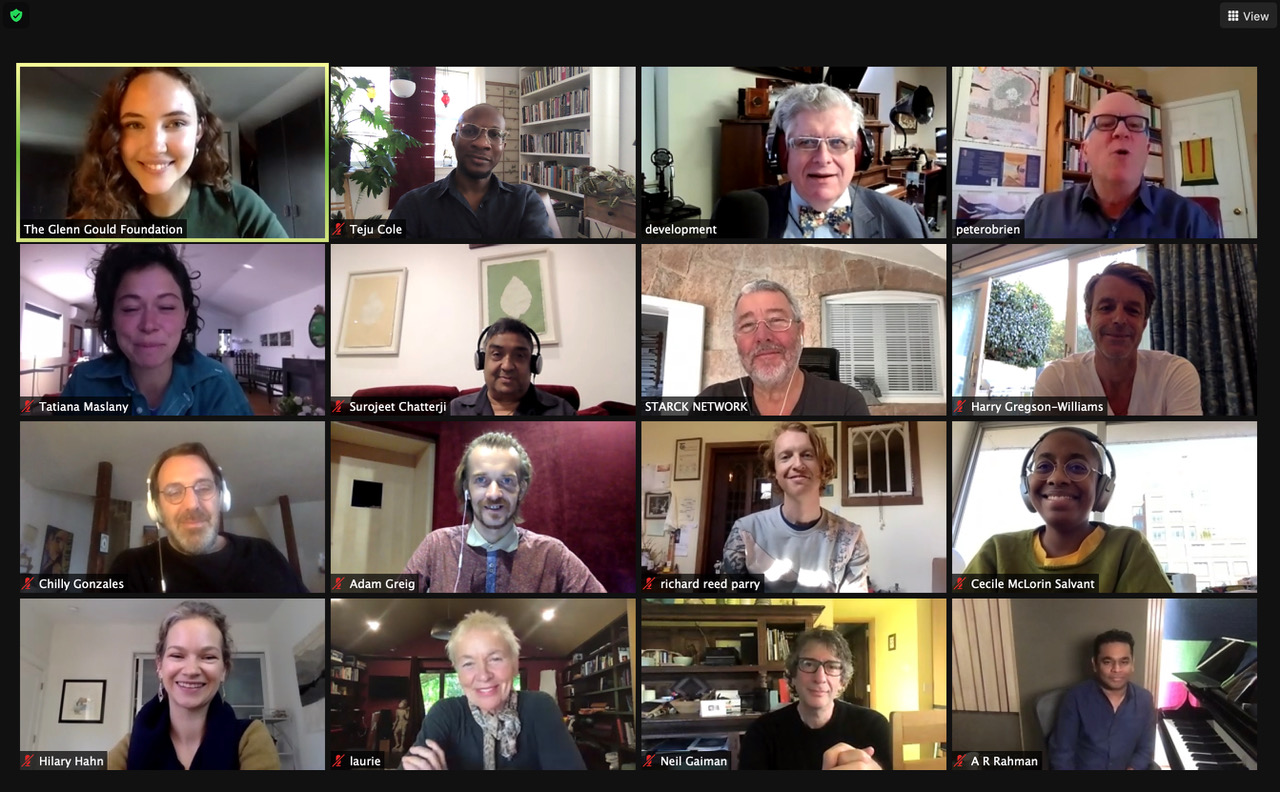

Richard Reed Parry, a core member of the Grammy Award-winning Canadian rock group Arcade Fire, was among the 13-person selection panel for the prize. The full panel included two other jurors from Canada, as well as jurors from the United States, India, France, Nigeria, and the UK.

“It’s such an amazing cast of luminous human beings and artists and writers,” Parry said.

Parry had interest in working on the panel in the past, but his touring schedule made that an impossibility. However, for this year’s prize he was able to participate in the panel via videoconference over an intense three-day period.

“It’s not just like everyone casts their vote and the thing is over. It was a very involved process that was very satisfying to be a part of,” Parry said, adding that many of the international panelists were up late into the night in order to take part. “We were basically off to the races as soon as we met.”

Parry highlighted Obomsawin’s 1988 album, Bush Lady, as one of the marquee pieces of work that he was struck by.

“There’s so much there over such an amazingly long career,” Parry said. “The work itself is amazing work … It is shining a light in places where lights have been criminally undershone.

Parry said not everyone on the panel was familiar with Obomsawin’s work initially, but it didn’t take much of a push for the final decisions to be made.

“What was remarkable was the degree of ease in which the entire jury moved towards her work,” Parry said. “The arts culture in this country seems to be deeply interested in trying to elevate [Indigenous] voices and cultivating more of an understanding of something that is much better than the reality we grew up with.”

Parry referred to a “grander-scale cultural reckoning” and push for reconciliation within Canada and across North America.

“There’s such a long, broken, traumatic history,” he said. “It feels like there’s, perhaps, there’s the beginnings of the awareness than perhaps there has ever been. And hopefully a lot of good can come out of that.”

Obamsawin echoed those sentiments when discussing what she’s observed over the last few decades in terms of progress for Indigenous rights.

“For me, it’s more than hope. There are a lot of good people that want to see justice done to our people. That’s what really excites me the most,” she said.

In addition to her own award, Obomsawin has been given the opportunity to provide a young artist with the $15,000 Glenn Gould Protégé Prize. While she does have someone in mind, Obomsawin isn’t quite able to release that information yet.

She does, however, have advice for young filmmakers and artists who might be seeking funding for their work.

“It’s not like it was even 20 years ago. Everything is possible,” Obomsawin said. “In any Canadian institution, there’s a space (for your work), a budget, there’s money addressed to young people or any age people who need help. There’s a lot of people out there waiting to help you.”