Image Caption

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Any issue of grief or condolence from Indigenous communities on the passing of Queen Elizabeth II yesterday, Sept. 8, has not matched the outpouring from non-Indigenous Canadians and their institutions.

That’s because Indigenous people are conflicted, says Courtney Skye, Indigenous policy analyst with the Yellowhead Institute, and they have a complex relationship with the Queen and the Crown.

“I’m hoping there’s room for the complexity of feelings that people have,” said Skye, who is Mohawk from the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory.

Elizabeth passed away at the age of 96 at Balmoral Castle in Scotland on Thursday.

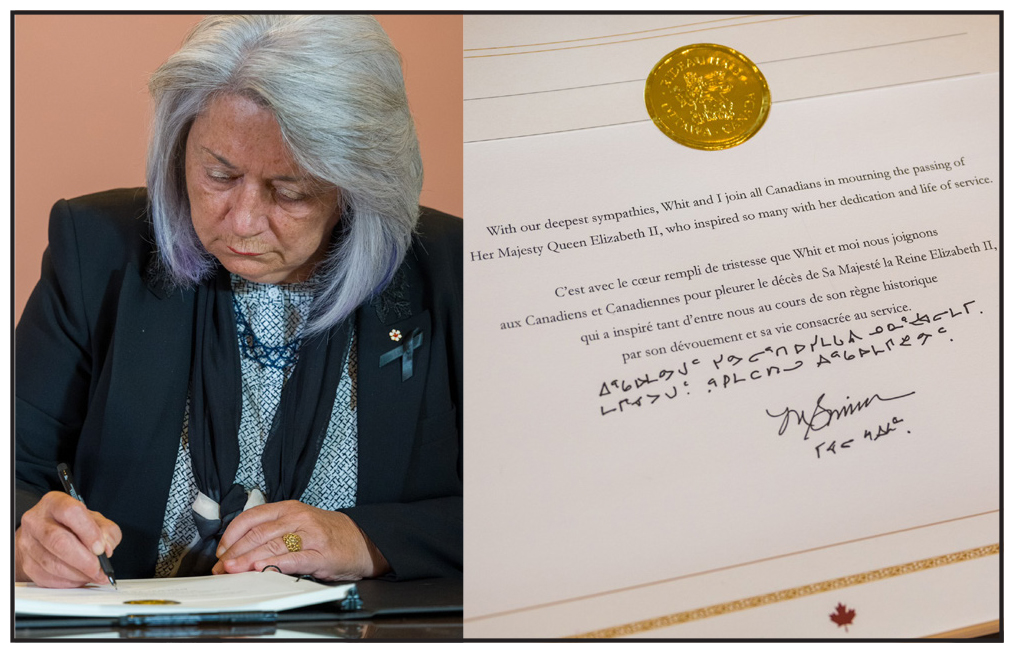

“For many of us, we have only ever known one Queen,” said Governor General Mary Simon in a written message yesterday.

“When I was growing up, my grandmother revered The Queen, as did so many in the Arctic. She would tell us stories about Her Majesty, about her role and her commitment,” wrote Simon, who, as an Inuk woman, became the first Indigenous person to be appointed as the Queen’s national representative in Canada in 2021.

For all those who “revered The Queen,” there were also those who denounced her. That dichotomy in the relationship she had with Indigenous peoples played out during some her 22 visits to Canada as well as other events.

In 1990, for example, the Treaty 7 Nations of the Blood Tribe and Siksika Nation held opposing viewpoints in attending a banquet in Elizabeth’s honour in Calgary. The Siksika Nation boycotted the banquet, which they were invited to as an after thought, while the Blood Tribe attended.

In 1994, Dene Chief Bill Erasmus very publicly expressed his dissatisfaction to the Queen during her visit to Yellowknife. He complained of the slow movement on land claims and said the federal government was not living up to the obligations to First Nations in the treaties signed with the British Crown. He said Canada had “tarnished and sullied” the Crown’s reputation as a result. The Gwich’in Tribal Council boycotted that visit because of Britain’s strong stance against fur trading. In other parts of the north, however, she was greeted with enthusiasm by Indigenous peoples.

Our report in Windspeaker’s back issue can be found here: August 29 to September 11, 1994.pdf (windspeaker.com)

In 2013, then Ontario Regional Chief Stan Beardy declined the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee medal, stating in a news release that “accepting the medal at this time would condone the fact that the British Crown and Canadian government are ignoring the legal and historical connection they have with treaty nations.”

On July 2, 2021, statues of Queen Elizabeth II and Queen Victoria on the Manitoba Legislature grounds were toppled in response to the unmarked graves that had been uncovered at two former residential school sites in the previous months.

This past May, when Charles and his wife Camilla were in Canada, leaders of the Assembly of First Nations and the Métis National Council requested an apology from the Queen, as head of the Church of England (Anglican Church). Between 1820 and 1969, the Anglican Church operated three dozen Indian residential schools and hostels. While the apology never came, Charles did emphasize the importance of reconciliation.

In response to Elizabeth’s death, Anishinabek Nation Grand Chief Reg Niganobe tweeted “heartfelt sympathies” and 300 Anishinabek observed a moment of silence at a Robinson-Huron Treaty gathering.

The Métis Nation of Ontario recognized the Queen for enshrining Métis rights by signing the 1982 Constitution Act, saying “all (were) inspired by her service.”

The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs and the Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief Cindy Woodhouse offered condolences and prayers in a joint statement, with Woodhouse saying, “As sovereign nations, First Nations in the Treaty territories located in Manitoba greatly value the sacred Treaty relationship with the British Crown.”

And there were personal messages of warmth from some, including Indigenous actor/singer Tom Jackson, who said he would sing for her on her journey to the spirit world.

Skye says there are Indigenous Nations that signed treaties with the Crown, so hold a direct allyship with Britain, “but I do think there has been a lot of instances where Canada and the Governor General, as her proxy in Canada, have really let Indigenous people down as treaty partners.”

Skye also points out that there are those Nations “who resisted being treaty partners with the Crown.”

For those with treaties with the Crown, Skye says, many believe those treaties are not being honoured “and so that disappointment often falls to Canada or the Governor General here, but I do think that’s represented by whoever’s head the crown rests on. Those expectations will fall on Charles.”

Charles, 73, succeeds his mother and is now king. This change in monarch has opened the discussion on whether or not Canada should leave the Commonwealth.

That’s a discussion Indigenous people need to be included in, says Skye.

“I think for Indigenous people, I think there’s probably going to be a lack of sensitivity for us as this historic partner, this historic relationship with the British Crown,” she said.

It is the treaty relationship that facilitated the creation of Canada as a colony, eventually leading to Canada becoming a country in 1867.

“I don’t think that nuance is going to be captured in a lot of the mainstream discourse around whether or not we want to maintain this relationship with Britain and remain part of the Commonwealth,” said Skye.

This is a time for reflection, she says, on where Canada’s authority as a country comes from.

“I would hope that would usher in conversations, conditional conversations that might even see provincial lines redrawn around Indigenous territories,” said Skye.

As signing treaties with the Crown has evolved Canada into the country it is now, Skye says perhaps further discussions about where Canada can go as a country outside of the Commonwealth can take place. However, there needs to be an understanding, she adds, that “the laws of the land that set down respect for our right as a distinct peoples" to govern, have been slowly eroded by Canada over time.

Skye says she would like any discussions that happen on Canada’s future to include the expansion of Indigenous control of territories and Canada to recognize Indigenous authority to self-govern “over certain plots of land in Canada (and Canada) actually cede that land to Indigenous people and their control over it and there be a…retreat of the colonial expansion of Canada.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.