Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

In 2021 and 2022 John Brady McDonald will have four books published. For most, that would make him a writer. However, McDonald calls himself a polymath, meaning a person with a wide range of knowledge or learning.

It’s a carefully chosen description that serves as “a slap in the face to every bigot, every narrow-minded individual who ever said, ‘You’re never going to do anything and you’re never going to go very far’.”

McDonald, 41, attended the Prince Albert Indian Residential School from 1984 to 1989. He grew up in poverty. His parents are also residential school survivors, who later were employed in the residential school system. McDonald points out that his parents shared with their children similar experiences of physical, cultural, emotional and sexual abuse.

McDonald is a writer, artist, historian, musician, playwright, actor and activist.

He also calls himself “stubborn” and says that’s one reason why he persevered almost 20 years to get his second book published by a traditional publisher. In between he self-published or had his written work included in other publications.

His stubbornness has also allowed McDonald to benefit from what he deems as a change in attitude that now sees Indigenous authors being considered legitimate writers.

“The fact that our voices are now being heard, it’s a wonderful thing. There are many of us when we first started our writing journey back then … it was easy to get categorized into this one little narrow niche of the Canadian literary world. I’m very happy that our voices are being heard and it’s out of a sense of it’s time for our stories to be told and we have an audience that’s willing to listen and it’s not tokenism anymore,” he said.

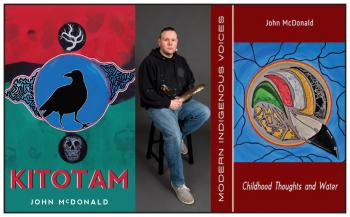

In 2021, McDonald had two volumes of poetry published, Childhood Thoughts and Water by Bookland Press and KITOTAM by Radiant Press. The two collections complement each other, he says, with KITOTAM a continuation of Childhood Thoughts and Water. The first book of poetry was “geared more towards rediscovering what was lost” while KITOTAM was “more of an exploration of my past.”

“We’re a fractured people learning a fractured culture second-hand with the bits and pieces the colonial dustpan missed,” said McDonald.

Electricity Slides, also published by Bookland Press and hitting the shelves this past December, is a fiction novel that started as live monologues McDonald performed for audiences.

“It was me wanting to go back to an experimental place and have fun with words again and to try to expand beyond a literal narrative, not so much an autobiographical narrative of my life, but wanting to explore this genre, explore poetry,” he said.

McDonald’s latest work, yet untitled and lacking a firm publishing date although targeted for 2022, is non-fiction in which he expands on his Facebook postings and social commentary looking at where Indigenous people are in the 21st century.

“It is my life. They’re my stories. They’re my way of looking at the world, the way the world is shaped, my views towards (that),” he said of the book that will be published by Wolsak & Wynn.

Despite Electricity Slide unintentionally addressing his own struggles of post-traumatic stress, his experience with an oppressive system, and his sexual identity and orientation, and his books of poems that talk about his past, McDonald says it is his upcoming book that lays him bare.

“While it’s easy to open wounds with poetry, it’s a cleaner cut. You’re able to manipulate the wound in a way. The pain’s still there, but it’s not as painful for you. Writing non-fiction, you can’t hide behind a turn of a phrase. It’s blunt… It is one of the most challenging books I’ve ever written…. That being said, I enjoy the process.”

McDonald says all four works have been cathartic, all for different reasons and all providing a different level of catharsis.

Childhood Thoughts and Water was his first publication after years and years of rejection. KITOTAM allowed him to share aspects of his childhood that he “wanted so badly for others to hear.” Electricity Slide, because of its experimental nature, was a book he was told was unpublishable.

With the upcoming non-fiction, “it’s like the next step in my career as a writer. As poets we often aren’t seen as legitimate writers in some literary circles…. With a book coming out, it provides that kind of being taken seriously.”

McDonald’s literary success coincides with a decision he made in 2021 to change his name.

“I was born John A. McDonald. If you’re a residential school survivor, an Indigenous person anywhere, to be named John A. McDonald, it’s a pretty heavy thing to be named. It was a source, for 40 years, an albatross around my neck,” he said.

His father was named John McDonald and passed the name and the initial “A” on to his son.

When the Saskatchewan government brought in legislation that allowed residential school survivors the opportunity to change their names, John Brady McDonald took it.

“Brady” is the name he claimed last year in honour of his grandfather, Métis leader Jim Brady.

“So I get to carry on his tradition while at the same time I’m still honouring my ancestors from the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation… and at the same time leaving behind this name that carries so much pain, so much negativity to our people,” he said.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.