Image Caption

Summary

Windspeaker.com Contributor

Two emergency resolutions were introduced and passed at the Assembly of First Nations Annual General Assembly in Fredericton on July 25.

They were in response to passionate debate on the resolution An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Metis children, youth and families—Transition and Implementation Planning. This resolution pertains to the child welfare legislation Bill C-92, which was passed through Canada’s House and Senate before Parliament rose for summer break.

Chiefs-in-Assembly came together to support each other’s separate approaches on ways to protect their precious ones—their children.

“In this process, what we’re doing is we’re helping each other because yes, there are differences, but we each have our responsibilities,” said Splastin Chief Wayne Christian. “It’s really about how do we actually work together.”

Christian had his name attached to all three resolutions.

The initial resolution called for First Nations to work within the federal legislation, which received Royal Assent in June. A Legislative Working Group, created by the Chiefs-in-Assembly, provided input into the development of legislation, policies and approaches to child welfare reform.

Numerous chiefs, some of whom were residential school and Sixties Scoop survivors, acknowledged that Bill C-92 wasn’t perfect, but spoke in support of the resolution which, in part, called for:

“Canada to immediately support and fund a First Nations led distinctions-based transition and implementation planning process for all stages of the comprehensive reform of child and family services, affirming the inherent rights and self-determination each First Nation has to decide what is most appropriate for their own peoples, without interference by Canada.”

The resolution also directed the AFN to establish a technical table to provide “input, oversight and guidance” during the national transition and implementation process.

“Our most important are our children and control of who’s going to care for those children,” said Muskowekwan First Nation Chief Reginald Bellerose, who moved the resolution.

“In the resolution there’s enough flexibility. It does not impede on any chief or council, it does not impede on anyone’s jurisdiction.”

“We all agree (this legislation) is not a perfect bill, but what it does is open the door for us to be able to exert our jurisdiction over our children,” said proxy David Pratt, second vice chief with the Federation of Sovereign Indian Nations.

Cheryl Casimer, proxy for the ?aq?am First Nation, said British Columbia was in a “unique situation” and had a tripartite table going with the federal and provincial governments to work on child welfare.

“We understand the legislation is flawed … but what we do need is we need that full recognition for us to be able to do the work necessary. This is a placeholder, as well, for future funding,” she said in support of the resolution.

Grand Chief Joel Abram from the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians said he understood why this resolution would work for many First Nations, but the AIAI would not support it.

“The Ontario region is opposing this motion on principle,” he said. “Going into this, we just came out of a battle against the framework (legislation) and AIAI in Ontario has led that fight in many respects …. So we see this as another extension piecemeal approach to implement the framework.”

Framework legislation had been vehemently opposed by First Nations countrywide to the point that the federal government scrapped going forward with it.

“What this legislation does, it transforms your law into Canadian law,” Abram told the chiefs. “We understand for many people it is better than what they have now, but for Ontario it’s not.”

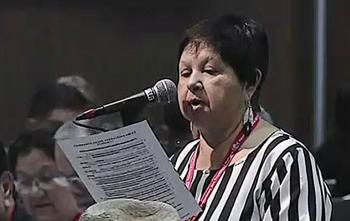

Serpent River Chief Elaine Johnston stressed that Ontario’s opposition to the resolution wasn’t about not prioritizing their children.

“It makes it sound as if I don’t care about our children and that is not true. I care very much about our children and I deal with child welfare issues every day. And I think the issue here is sovereignty and our different approaches,” she said.

Johnston asked that chiefs let Ontario table a resolution that would allow them to proceed “in a different way.”

That resolution was tabled the following day along with a resolution from B.C. The two resolutions, which were both passed, supported specific approaches to transition and implementation planning for child welfare for Ontario and B.C.

Both resolutions, like the initial resolution, stated that nation-to-nation and First Nations regional tables would take priority over a national table when developing implementation plans for Bill C-92.