Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer says it isn’t always easy walking between two worlds, that of Indigenous knowledge and that of western science.

And that’s where the braiding of sweetgrass comes in.

Kimmerer is a mother, botanist, writer, environmental biology professor and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She spoke to hundreds of people via Zoom in an event hosted by the University of Calgary’s Arts and Science Honours Academy special guest lecturer series this past Tuesday.

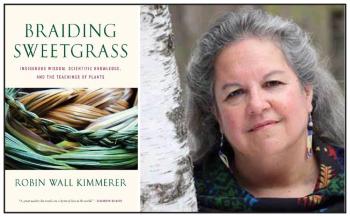

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and Teachings of Plants is not only a book written by Kimmerer, which has received wide acclaim, but its title represents an understanding of knowledge.

“The three strands represent the ways of knowing the world,” said Kimmerer, speaking from her home in Syracuse, New York.

For her they represent traditional ecological or Indigenous knowledge and scientific ecological knowledge, both of which are “human ways of knowing.”

“(But) we’re not the only ones here. We’re not the only beings with knowing. The third strand in these braids refers to the knowledge of the plants themselves,” she said.

The answer to caring for the earth lies in braiding together these three strands.

“The relationship between those three strands of knowledge has not always been clear or easy for me,” said Kimmerer.

Growing up, plants were as much Kimmerer’s teachers as were people. So when she went to university and was told she was wrong, that science considered plants and nature as objects and only one species – humans – were most entitled to the riches of the earth, she realized she had “unwittingly stepped out of my Indigenous paradigm.” She came to the conclusion that her way of thinking was not welcomed.

But the earth isn’t agreeing with how it has been treated.

It’s no longer what more can we take from the earth, but what does the earth ask of us, said Kimmerer.

“I think the earth asks us to change,” she said.

There needs to be a shift from the western view that sees land as a source that can be exploited for ecosystem services, property, natural resources and capital.

Indigenous peoples have a “very different framing of what land means,” said Kimmerer. Land provides identity, sustenance, residence, an ancestral connection, knowledge and spirit.

“Land is a place where we enact our moral responsibility because the land is sacred,” she said.

Kimmerer believes that it’s not about the emerging sciences that tell us how to harness nature and develop commodities.

“What I’m really interested in is what do the plants have to teach us about how we might live, particularly at this moment at the crossroads, of that fork in the road of climate change… The plants are our earliest teachers,” said Kimmerer.

To make her point she references the Branson Virgin prize. It was a 2011 competition that offered a $25 million prize for anyone who could develop a commercially viable design that would result in the permanent removal of greenhouse gases from the earth’s atmosphere for at least 10 years as a means to combat global warming. Eleven finalists were announced but the prize was never awarded. Eventually it was discontinued.

Kimmerer said there is already a system that stores carbon dioxide away and has for eons while making oxygen and building soil.

“It generates biodiversity at the same time and it makes us happy and peaceful and it’s called a forest. I say give the prize to the trees, to the forest, because natural solutions for climate change as taught to us by the intelligence of plants have to be part of our problem solving,” she said.

The focus needs to be put on system change and not climate change, she adds, to recognize the impact of the carbon footprint left by corporations, institutions and governments.

“As a plant ecologist I really want to endorse, alongside political solutions, economic solutions, technological solutions, we need all of them in these really urgent times when we understand we have perhaps two decades at best to solve these problems (of climate change), we need to ally ourselves with the plants and help them help us,” said Kimmerer.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.