Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Lynn Gehl finds it difficult to celebrate the legal victory that gave her First Nation status.

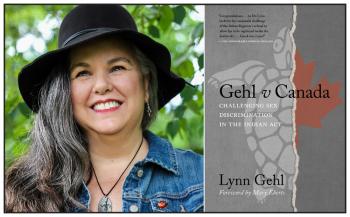

Gehl, Algonquin-Anishinaabe-kwe, who holds a Doctorate of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies, details the painful toll the 23-year battle with the federal government took on her life in the recently published book Gehl v. Canada: Challenging Sex Discrimination in the Indian Act.

“It’s really a book about power, in terms of my family, in terms of community, the department of Justice…. I think I had a millimetre of agency, less than a millimetre of agency and it was all thwarted by Canada. That’s depressing, right?” said Gehl.

Agency, or spirit agency, is defined by Gehl as “the term that critical theorists use to talk about a person’s ability to move forward, to have capacity to move forward. Indigenous people would talk about having spirit.”

Gehl began her oral research with her grandmother and archival research in her 20s as she worked toward gaining “Indian” status. In 1994, when she applied for status, she found that amendments made to the Indian Act in 1985 made it impossible for her to claim it.

Under the Indian Act, the registration of an individual is based on the status of both parents. However, a policy on unknown or unstated parentage made it impossible to gain status for those who either could not trace their paternal line or who did not have their father recorded on their birth certificate.

In Gehl’s situation, which played out over decades, the department then known as Indian and Northern Affairs and then Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), determined that she did not qualify for status because her grandmother had not identified Gehl’s grandfather. Government policy assumes an unlisted father is non-Indigenous.

Gehl initially wanted to fight the status decision based on how the policy was implemented. She was told she needed to bring an action declaring the Indian Act violated Sect. 15(1) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. That section states, “Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

The action was dismissed, so Gehl appealed to the Ontario Court of Appeal. Then finally, in 2017, the Court of Appeal found that it was unreasonable to deny Gehl status and declared she was entitled to Indian status.

Justice Sharpe made his decision based on the Charter, declaring the Proof of Paternity Policy “perpetuates the long history of disadvantage suffered by Indigenous women.” The other two judges applied administrative law analysis in order to decide the case.

Two years after that decision and following extensive consultation with First Nations, the government brought in amendments to Bill S-3, extending entitlement to descendants of women impacted by sex-based discrimination dating back to 1869. Gehl said government’s response “didn’t resolve all the issues, but it did go a long way.”

Gehl is quick to point out that other women have worked hard, as well, to bring about equality.

In fact, she created the Indigenous Famous Five—Mary Two-Axe Earley, Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, Yvonne Bedard, Sandra Lovelace Nicholas, and Sharon McIvor. It was a play on the better known “Famous Five,” a group of white women who brought court action in the 1920s that resulted in women being seen as persons under Canadian law.

“I did it consciously and intentionally after the Famous Five as a way to give it currency,” said Gehl. “It was more political strategy and it wasn’t even fun to do that. It was something that we had to do. I think some people were actually annoyed by that, or mad by that because they were saying things like, ‘Who chose you?’ It was a political strategy. We weren’t going to go out and get consensus among Indigenous women.”

The Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action grew the group to the Indigenous Famous Six, removing Earley, who had passed away, and adding former senator Lillian Eva Dyck and Gehl.

“I certainly was happy and proud to be included…. If I was excluded, I would be very sad about that. I would feel disenfranchised because I have been doing a lot of work on the issue. So how do I feel about that? I feel that it was something that we created, we put ourselves in the spotlight for the purpose of giving the ideology currency in the collective consciousness. It wasn’t about me. It still isn’t about me,” said Gehl.

Gehl is clear that it was a fight she took on because she felt the policy that excluded her from gaining status “was immoral and they were harming Indigenous mothers and children and I had to do something with my life anyways. And why not serve Indigenous mothers and children? I don’t like that it took that long. I’m actually quite miserable about the fact it took so long. I think that my court case illustrates the extent Canada will go to to deny Indigenous people who they are and target mothers and children.”

Gehl says difficult decisions had to be made during the fight and not everybody understood. Sometimes she felt alone and undermined.

“People are emotional. They’re not necessarily political strategists who understand how hard it is to move through power and some of the hard decisions that you have to make in doing that. But not only that, how pissed off you can get,” she said.

One criticism Gehl constantly faced was that she was fighting for her status under the Indian Act, a colonial construct. She was called a “colonial Indian.”

She points out that many young mothers are dependent on the Indian Act to get health and other benefits.

“Me caring for them doesn’t make me having a critical colonial mindset. It means that there are some people who are very dependent on Indian status registration and there’s no reason why I can’t concern myself with that as well as understand that the Indian Act is problematic and we’re getting out of the Indian Act,” she said.

But “tying up her agency” for so long wasn’t what Gehl was after. In fact, she calls it a “life-sucking matter.”

However, she asks, when would have been a good time to call it quits? Five years or 10 years or 15 years into the battle?

“At some point when you’re 15 years into it, you’re not going to quit. If I quit, it would mean that some other woman, mother would have to pick it up,” said Gehl.

In the book’s foreward, Mary Eberts, a counsel for Gehl in her legal matter, writes, “The book is unique because it is the only full-length, first-person account of a leading case about discrimination against women in the Indian Act of Canada. Gehl v Canada is the fifth in the series of iconic court challenges to Canada’s long-standing attempt to assimilate Indigenous Peoples by expelling Status Indian women from their communities.”

While the book may be unique, Gehl says it certainly wasn’t therapeutic to write.

“It was miserable. It was miserable. I don’t feel this joy and pride in being a Famous Six. It was entirely a miserable process of walking through genocide,” she said.

Gehl v. Canada: Challenging Sex Discrimination in the Indian Act is published by the University of Regina Press and is available at https://uofrpress.ca/Books/G/Gehl-v-Canada.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.