Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

This year’s five finalists for the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust non-fiction award are changing the face of the decades-old prize. Three Indigenous writers and one Black writer have made the cut.

“It’s about putting whiteness to the side. It’s important to centre the stories of this land that was formed by Indigenous and Black people who were exploited to develop this land,” said Terese Marie Mailhot, one of three jurors.

Mailhot is from the Seabird Island First Nation in British Columbia. She now lives in Indiana where she teaches at Purdue University. Her memoir Heart Berries was a finalist for the Hilary Weston prize in 2018.

“For me to be able to try and decentre whiteness as a judge and focus primarily on the art and what’s transformative about it, it’s like having real elective power to pay attention to the books that may be overlooked typically because people don’t understand the cultural references and they don’t understand Indigenous identity; and when people are writing about it, what is artistic and what is testimony. It’s been really good to be on the other side of things and feel you have some real agency to change things,” said Mailhot.

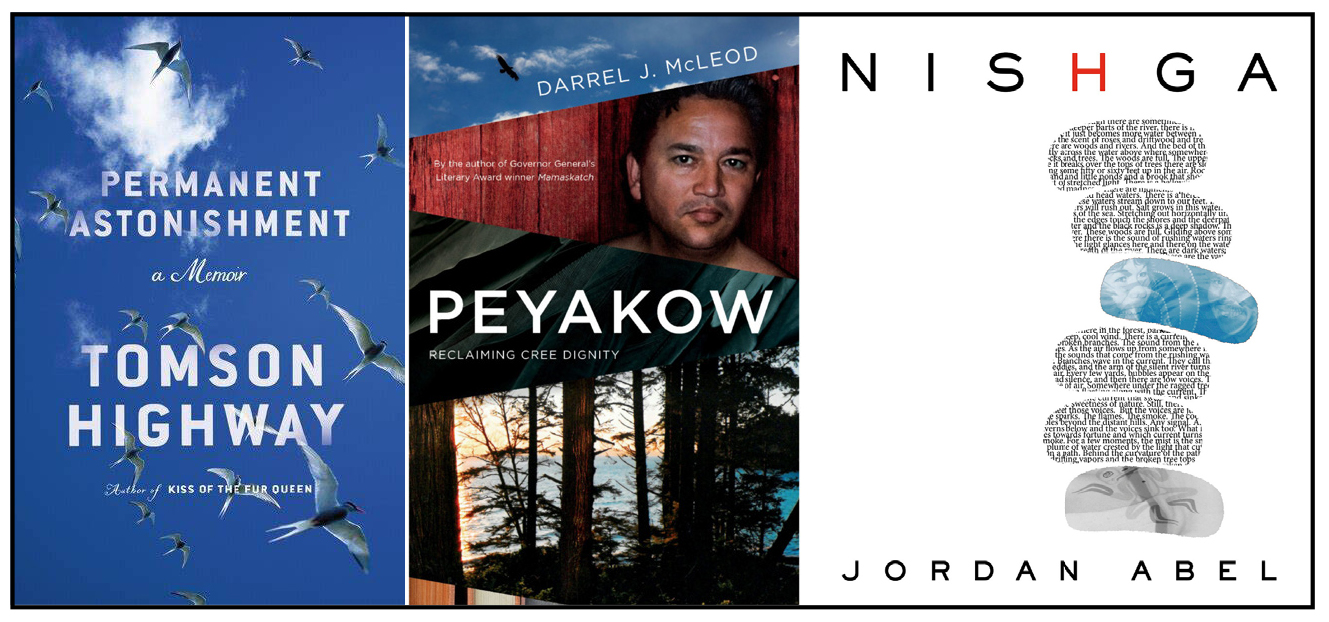

The three Indigenous writers shortlisted are Tomson Highway for Permanent Astonishment: A Memoir (published by Doubleday Canada); Jordan Abel for Nishga (McClelland & Stewart); and Darrel J. McLeod for Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity, A Memoir (Douglas & McIntyre).

For all three award-winning writers this is their first nominations for the Weston award, although this marks Highway’s fifth non-fiction work. McLeod’s first memoir, Mamaskatch, received the Governor General’s Literary Award for Non-fiction in 2018.

Since the Weston award began in 1997, it has been presented to an Indigenous writer only once and only to a handful of non-white writers. In 1998 Stolen Life: A Journey of a Cree Woman, a collaboration between Yvonne Johnson and non-Indigenous writer Rudy Wiebe, won. The book is Johnson’s autobiography.

It took 15 years until another Indigenous author was a finalist. In 2013 Thomas King made the shortlist for The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. In 2014, his novel won the RBC Taylor Prize, given to the best Canadian work of non-fiction.

Four years later, prize-winning journalist Tanya Talaga earned her first of two spots in the top five with Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death and Hard Truths in a Northern City (2017). All Our Relations: Finding the Path Forward was nominated in 2019.

Mailhot is disappointed about the limited representation Indigenous writers hold in the Hilary Weston portfolio.

“We’ve been writing since, literally, literature began!” she said.

“The conversation about representation is way complex because it’s not like representation fixes things, but if we don’t encourage those books by giving them shine, they don’t get made is the whole point. Publishers don’t pay attention if they’re not up for major Canadian awards.”

She points to the lack of representation by women writers in this year’s finalists, acknowledging that people will be “upset.” However, she also points to the list of 107 titles from 64 publishers that were up for consideration.

“I think that’s the submission process. There’s a lot of disparity in terms of representation because it’s the top five publishers (that) usually do end up in the final round of any kind of book award. Big publishing really needs to turn it up a notch and publish more texts by women of colour,” she said.

Eligibility criteria allow publishers to submit two non-fictions for consideration. However, publishers with more than 10 eligible non-fiction titles can add one book for every additional 10 eligible books up to a maximum of five.

“There’s a disparity in everything in publishing, down to who has events and who has representation in terms of agents who can actually fight for the book and get it what it deserves in terms of care and consideration and also money,” Mailhot said.

She credits the support she received by other women writers using their platforms and careers in getting Heart Berries on the New York Times bestsellers list.

“I don’t think it was a publishing thing because I honestly don’t think they were looking for memoirs by Native women, let alone a memoir that was 100 pages long. I think already they were, ‘No,’ but I think they didn’t realize that once it was published it would resonate especially with women because it’s about trauma,” she said.

Mailhot also notes the disparity in the Weston award ceremony. The year she attended as one of the finalists, she was accompanied by an Anishinaabe friend.

“We felt like the only people of colour in the whole award ceremony. We were trying to take selfies in our seats and I was, ‘No, there’s a sea of white behind us, we can’t take a selfie,’” she said.

“I was able to bring up to … Weston that they do need to make the event itself more inclusive so that nominees aren’t the only people of colour present.” Lindsay Wong, of Asian descent, was also a finalist that year.

Mailhot says she understood two things about her work when she was a Weston finalist: that it would set her up well for her next book and that she wasn’t going to win.

“I’m a Native woman and I was writing a very Indian text. I think they weren’t going to get why it was fragmented and they weren’t going to get the references to intergenerational trauma or what I was trying to do on the page. I think they would understand the art, but I think my position made them doubtful of my talent because it’s a craft question really. When people are judging they think that they’re primarily focused on the literary art, but really they don’t know their biases,” she said.

Mailhot is only the third Indigenous writer to be a juror for the award, following in the footsteps of James Bartleman (2012) and Helen Knott (2020).

Mailhot says she and the other two jurors, Kevin Chong, of Asian descent, and Adam Shoalts, had good discussions about the books submitted and didn’t argue.

“It was the first time I’ve ever been a judge and I was very much so respected and was able to voice my opinions and part of that is my maturity now as an artist that I’ve been able to say, ‘I don’t like this, I think we should do this.’ I think having that autonomy places me really well for being a judge, made it easier to be a judge now as opposed to early in my career,” she said.

Judging wasn’t easy, she says, adding she wishes she could have selected 10 books.

“What I’m looking for is work that transcends the genre and pushes the form in terms of the art, and memoir is the best place for that because in journalism and history writing there’s not much you can do to push the form or make it new,” she said.

Comments from the jury on the three Indigenous-authored memoirs are glowing.

About Abel’s Nishga, they say, it “defies the boundaries and traditions of memoir to achieve something singular and necessary.”

About Permanent Astonishment, “While unstinting about the abuse he and others suffered, Highway makes a bold personal choice to accentuate the wondrousness of his school years resulting in a book that shines with the foundational sparks of adolescence: innocence, fear, and amazement."

About Peyakow, “McLeod’s vibrant prose renders the world with tenderness and skill. His profound book is full of love and trouble that you won’t soon forget.”

The other two finalists are Disorientation: Being Black in the World (Random House Canada) by Ian Williams, and On Foot to Canterbury: A Son’s Pilgrimage (University of Alberta Press) by Ken Haigh.

“There are so many Native women (writers) that I love and if there had been a book like that I would have fought for it,” said Mailhot.

“I hope that next year there’s just more work published (by women writers). We can’t fix all of publishing’s problems in one literary round but I think the odds are pretty good for these books to get shine and also for next year to be better.”

The winner will receive $60,000 and each of the finalists will receive $5,000.

The winner will be announced Nov. 3.

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.